Lebanon's elite seeks legal loopholes to evade justice for corruption

“Revolution is not a change of governance, it’s a change of society,” Nizar Saghieh, a lawyer with the watchdog Legal Agenda, told a crowd of protesters gathered in Beirut on Tuesday.

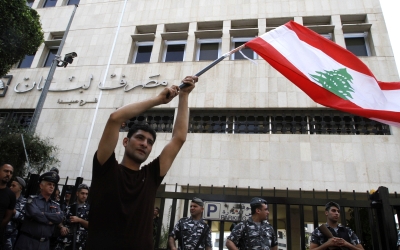

As the Lebanese popular uprising that started on 17 October approaches the one-month mark, lawyers have become torchbearers for the thousands looking for an alternative to systematic patronage, judicial failures, electoral fraud, bribery, cronyism and clientelism.

Transparency International ranked Lebanon 138 out of 175 countries in its 2018 corruption perceptions index, making the country one of the worst in the world.

The tug-of-war between the sectarian political establishment and those demanding its demise has morphed into a legal battle this week, as protesters called for the approval of anti-corruption amendments.

Meanwhile, politicians have set their sights on an amnesty bill that could provide immunity for a number of crimes many in the country's political class are alleged to have committed.

A parliamentary session scheduled for Tuesday was cancelled following demonstrators’ calls to block the roads and prevent the general amnesty bill from going further - even as the shutdown also prevented parliament from voting on amendments to corruption laws called for by protesters.

Amid much confusion over what the amnesty bill entails and whether amendments to existing laws would be sufficient to retrieve stolen public funds, lawyers and civil society groups have sought to raise public awareness and illuminate the way ahead.

Amnesty for some more than others?

Amnesty laws are particularly controversial in Lebanon, where this type of legislation is also related to the country's civil war. When the 15-year war ended, Lebanon passed an amnesty law that condoned crimes committed prior to 28 March 1991.

Unlike Europe, where this legislation focused on pardoning all crimes committed in the course of World War II except those against humanity, Lebanon pardoned all crimes except those committed against political leaders. The 1991 amnesty law therefore strengthened the position of militia leaders, who then went on to rebuild state institutions.

“The message was that political leaders are above the rest of society,” Saghieh said.

The new amnesty bill, the lawyer added, would once again keep politicians above the law.

The current amnesty bill has wide popular support in the cities of Tripoli and Saida, where the crackdown against individuals suspected of ties to groups such as the Islamic State (IS) resulted in numerous arrests.

The right to a fair trial often takes the back seat in terrorism cases, as human rights watchdogs have documented many instances in which the accused have been detained without trial or held past the end of their sentence.

Placing the general amnesty bill on the parliamentary agenda at a time of unprecedented popular protests is therefore seen as a move to garner populist support.

But, lawyers warn, a new amnesty law also risks clearing politicians’ slate in the process.

Speaking to protesters in front of the Grand Serail, the Ottoman headquarters of the prime minister in Beirut, Saghieh warned that the amnesty law could pardon all crimes unless explicitly stated otherwise.

While many "ordinary" crimes are explicitly listed as not included for amnesty, Saghieh noted that "a number of dangerous things are not mentioned” - among them environmental crimes, tax evasion, intimidation and extortion, crimes which many Lebanese politicians stand accused of committing.

Julien Courson, executive director of the Lebanese Transparency Association, agreed that an amnesty law must be approved, but that it should specifically focus on those who have been wronged by the justice system.

As it stands, the proposed law “contradicts Lebanon’s commitments to international law and increases the gap between the people and the political class”, Courson told MEE.

Parliament member Yassine Jaber said that those accused of financial crimes would not benefit from the proposed law, but according to Courson the text of the law is too ambiguous to rule out this possibility.

Combating corruption - but how?

The Lebanese legal system already allows for the prosecution of corruption and the recovery of stolen assets - but the country still needs an independent judiciary and the political will to carry out the task, changes the protesters have been calling for.

In the past, some MPs and civil society movements put forward draft amendments and bills related to tackling illicit enrichment, combatting corruption in the public sector, and establishing the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC).

None of these proposals were ever approved by parliament.

According to Courson, a bill to establish the NACC was first put forward in 2008. President Michel Aoun has since used his constitutional powers to amend the bill and send it back to parliament for discussion.

Aoun amended the bill so that NACC judges would be elected by the MPs, Courson said - a proposal that the Lebanese Transparency Association and other watchdogs claim would compromise the independence of this institution.

Parliament was due to discuss on Tuesday a bill, put forward by members of the political establishment as an alternative to the NACC, to establish a special court for fiscal crimes. In this instance too, the institution would be presided over by judges elected by MPs.

A dedicated minister for combating corruption appointed by the last cabinet only tackled two corruption cases since 1992 - further stoking fears that any corruption plan backed by the political elite would do little to effectively address the issue.

Gina Chammas, a leading anti-corruption expert with the American Anti-Corruption Institute (AACI), said she opposed any bill or amendment put forward by politicians.

“We believe that these people will definitely not be able to make a proper law when it comes to holding themselves accountable,” she told MEE.

By law, banking secrecy is automatically lifted in cases of corruption, illicit enrichment and embezzlement of public funds.

'These people will definitely not be able to make a proper law when it comes to holding themselves accountable'

- Gina Chammas, anti-corruption expert

In such cases, the president of the republic, the president of the Chamber of Deputies, and the president of the Council of Ministers, judges, and other public servants are required to disclose their financial assets in a sealed envelope to their relevant councils.

But despite this legislation being in place, the information is not readily available to the public.

For Chammas, putting the political class on trial would require lifting the immunity granted to public officials.

Prosecution of the president and ministers requires the consent of the Supreme Council for the Trial of Presidents and Ministers, comprised of eight senior Lebanese judges and seven deputies chosen by the parliament.

Despite the legal hurdles ahead, Chammas said a team of Lebanese certified anti-corruption experts is working to find legal ways to bring about accountability.

“We want our [legal] actions to stand up in the best courts in the world [and to be] proper and fair so that there is no doubt about the sentence we will hand out,” she said.

Chammas noted that the failure to unify the legal definition of corruption to international standards created loopholes that made it difficult to open such cases.

“This is evidence that is absolutely no intention to allow any anti-corruption efforts to succeed in the country,” Chammas said.

But while political leaders hold on to their seats, society around them is changing and, protesters say, bringing about a revolution.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].