The fate of Egypt is with the people - and Sisi knows it

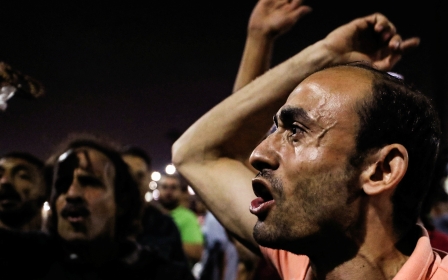

When I am told that the Egyptian people are no longer interested in revolution, I like to share a memory of something that took place nine years ago, on 11 February.

The roads around former President Hosni Mubarak’s presidential palace were surrounded by us, the people. That’s the romantic view; in reality, "the people" were very much divided between the anti-Mubarak and pro-Mubarak camps, with the latter constituting a definite majority.

Barricades were in place, secured by the presidential guard to keep people from clashing. But that did not keep the pro-Mubarak crowd from cussing and hurling insults at us, the ones taking action to unseat him. “How dare you do this?” they shouted. “He’s like a father to you.” Others asked “who paid” for us to be there, or called us “traitors”.

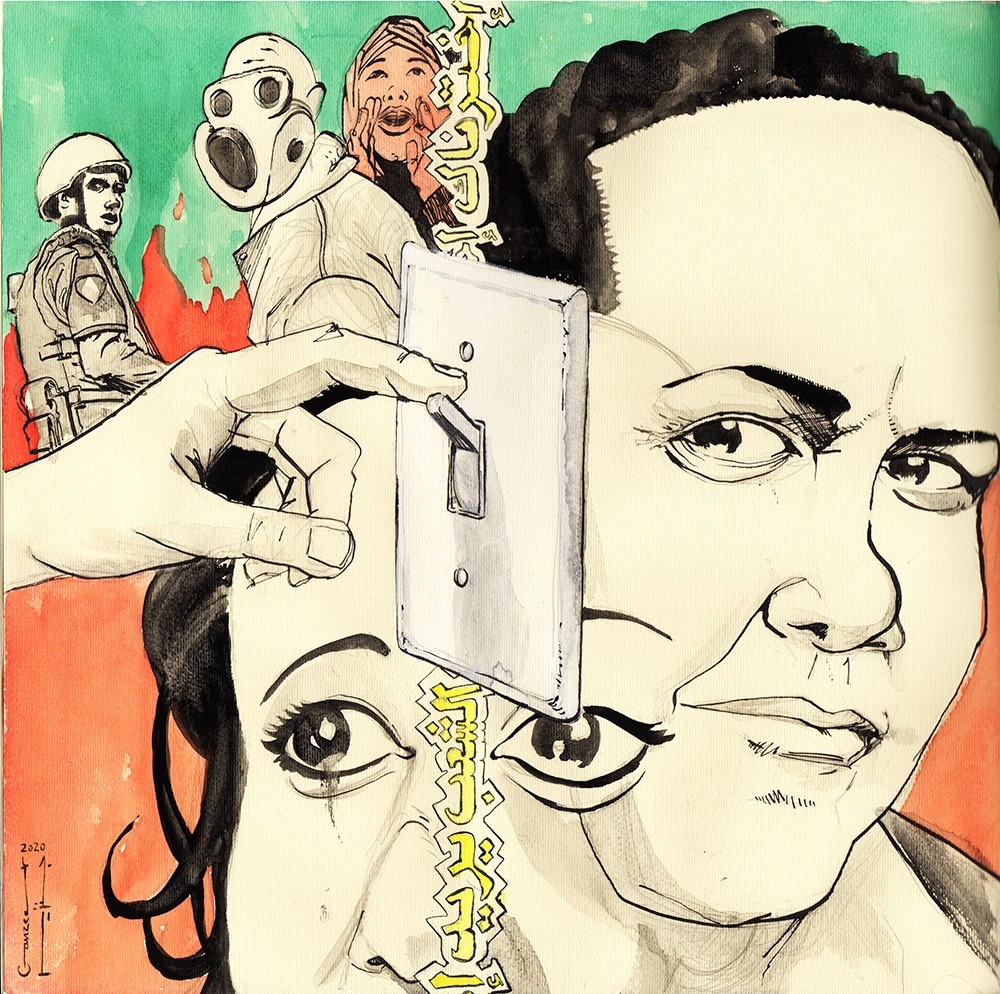

Flipping a switch

All it took for them to change their tune, though, was the announcement of Mubarak’s removal. It was like a switch had been flipped, and suddenly the crowds surrounding us - the ones who had called us traitors - burst into cheers of joy. None of the protesters held grudges; they hugged and danced the night away with the same people who had seemed so ready to assault them just moments earlier.

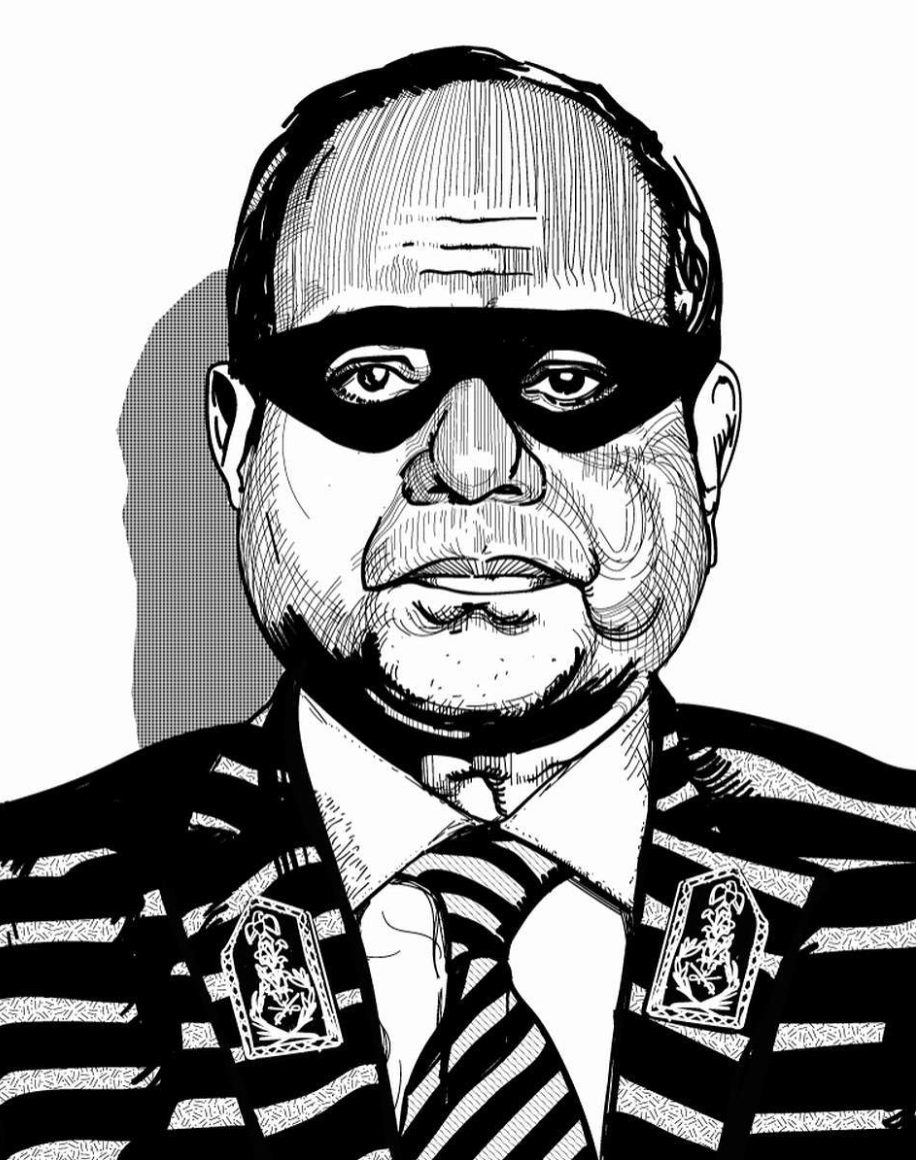

Today, those who seemingly side with dictator Abdel Fattah al-Sisi don’t do it out of honest conviction, but rather out of a need for protection. They’re siding with the one who has more power and influence, because that is the safer thing to do. At the end of the day, most people everywhere just want to ensure safety for themselves and their families.

Those who seemingly side with dictator Abdel Fattah al-Sisi don’t do it out of honest conviction, but rather out of a need for protection

But no one wants to appear unprincipled, so they trick themselves into believing that the blatantly evil person they’re siding with is the “good guy”, and they eat up all the propaganda spun around him - that he’s keeping them safe from “terror”, that international relations are improving, that he’s stomping out corruption at home, and that his economic policies are impeccable. They do so even if all indications prove otherwise, because it’s the safest thing to believe, at least in the short run.

If the events that took place nine years ago are any indicator, however, all it takes for millions of people to see the error of their ways is a flick of a switch - when the tables have turned, and the guy they’ve been siding with is on the losing end. It’s not about principles, facts or doing the right thing.

For this reason, when voicing discontent over Sisi’s rule, the response is often in the form of a question: “What’s your game plan?”, or “Who will lead the country next?”, or “How will he be removed from power?”

Ruling by fear

These questions are similar to the ones asked when Mubarak was still president. During his 30-year rule, nobody could have ever envisioned a presidential election with 13 candidates (as was the case in 2012, Egypt’s first free election). Had they attempted to imagine it, they likely wouldn’t have pictured many of the candidates who actually ran.

They certainly wouldn’t have imagined Mohamed Morsi as the elected president, someone who was never a public figure, and who very few people even knew existed. Even Sisi was not well known among the public prior to orchestrating his coup against Morsi in 2013, a move that catapulted him into the public consciousness and painted him as a hero of the people.

This move would not have been possible had Morsi and his Muslim Brotherhood party been considerate of the hopes and aspirations of the Egyptian people at large, and had they not royally screwed up during their mere one year in power, bringing the country to the brink of civil war.

That was why the Egyptian people seemed to welcome Sisi’s coup with open arms. Little did they know, what they’d get in return would be hundreds killed in Rabaa Square and in Sinai, more than 7,400 civilians facing military tribunals, more than 2,400 death sentences handed out by Egyptian courts, and more than 60,000 political prisoners.

That’s not even accounting for the many cases of forced disappearance, or the fear tactics employed to strike down the right to public assembly, or the various authoritarian measures taken to end what little free press the country enjoyed. Then there are the economic policies that have sent more than 32 percent of the Egyptian population below the poverty line.

Western complicity

By all indications, Sisi is no good for Egypt. Even if one were to ignore all the numbers, just the fact that he went from claiming no interest in the president’s office to altering the constitution to stay in office until 2034, clearly signifies his ill intentions.

What may surprise some people - particularly those oblivious to the colonial horrors of imperialism- is the more-than-amicable relationship between Sisi and other supposedly democratic governments

A clever administration - one that truly cared for the future of its population - wouldn’t curb freedom of expression and make enemies of its own people. It would make space for people to voice their grievances, and use those grievances as a guide for proper governance. But this is something neither Sisi nor the military establishment backing him care for.

This should come as no surprise to anyone. But what may surprise some people - particularly those oblivious to the colonial horrors of imperialism and their relation to postcolonial practices - is the more-than-amicable relationship between Sisi and other supposedly democratic governments.

Case in point: France saw no problem in selling Rafale combat jets and military satellite systems to Sisi’s regime. The sale of German arms to Egypt increased by 205 percent under Sisi; and the US continues to provide more than $1bn in military aid to Egypt. This, despite Sisi opening up Egyptian military bases to the Russian air force.

This should be concerning to people represented by “democratically elected” governments for two main reasons. Firstly, it is highly likely that these governments are dealing with Egypt without the public’s knowledge, so is that really democratic? Secondly, how likely is it that a government that cares little for democracies elsewhere will care at all about democracy at home?

Principles are not subject to contradictions. If one is willing to overlook injustice in one place, then one is able to overlook injustice anywhere - and that is a very dangerous trait for governing politicians to have.

Reasons for hope

So far, we’ve painted an awfully bleak picture. We’ve established that most people have few principles, that the Egyptian military does not care for the Egyptian people, that Sisi is the worst leader the country has seen in modern history, that he may continue to wreak havoc until 2034, and that “democratically elected” governments worldwide don’t really care and are willing to continue conducting business with him.

But if you read between the lines, you’ll see that hope and the potential for justice to prevail is embedded in the sequence of events that led to where we are right now.

Firstly, unseating Mubarak never required a massive majority. It was made possible by a persistent minority that was adamant about speaking truth to power, against all the odds.

Secondly, the next president needn’t be known prior to coming forward. He or she can surface after the fact (Morsi) or during the course of action taken (Sisi). And ideally, one’s drive to stand against injustice should never hinge on the viability of future presidential candidates, which is an absurd notion.

Lastly, and far more importantly, the fate of a people is always with the people. Even Sisi knows this. To stage his coup, he had to wait until enough seething discontent against the Brotherhood was fostered, in order to guarantee the unwavering support of the Egyptian people for his big move.

That is why he is now putting all the resources at his disposal towards keeping Egyptians from freely expressing their opinions; he knows all too well that he no longer has the support of the Egyptian public at large, and if given the chance - even the slightest opportunity - the people will rise up and swiftly remove him from power.

Absolutely anything the people want is possible, but only if they want it badly enough.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].