Iran elections: How Khamenei is closing down the reformists

“If the last corrupt regime [of the Shah] had given people the freedom to choose,” Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said on 11 February, “there would have been no need for a revolution” in 1979.

Speaking to thousands of people gathered in Azadi Square in Tehran to commemorate the 41st anniversary of the Islamic Republic, Rouhani continued: “The revolution happened because the gate for elections had been shut.”

The statement was shocking, as it clearly referred to the massive and unprecedented disqualification of reformist and moderate candidates from Iran’s parliamentary elections on 21 February, by the ultra-conservative Guardian Council that vets candidates.

Curbing the competition

Rouhani has been continuously attacking the disqualifications over the last few weeks. “People favour diversity,” he said on 15 January. “Don’t upset people. Don’t tell people that for every seat [in the parliament] we have 17, 170, or 1,700 candidates. Let us see that those 1,700 candidates are from how many factions … This is like a shop that offers 2,000 items, but all are the same commodity.”

Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who is in control of the Guardian Council, without naming Rouhani, countered his attacks on 5 February and stood behind the council. “How come the election is correct when it ends in your favour, but it is defective when it is not in your favour?”

Iranian society is fragmented into two hostile factions. The crisis in Iran is the result of a growing conflict between conservatism and modernism

Here is what the ayatollah is defending: the reformists are not even able to announce the list of their candidates to run for 30 seats allocated to Tehran, the capital. Initial reports show that out of 762 reformists who registered to run, only 44 have qualified.

The Reformists’ Policymaking Council says more than 90 percent of their candidates have been eliminated. As it stands, more than 160 seats (out of 290) will be won by conservatives, as there is no competing candidate from any other political faction. Conservatives will thus be in control without facing any competition.

It seems that the deep state led by Khamenei has made its decision: the “dual ruling system”, of which “reformists and moderates” were always a part since the emergence of the reform movement in 1997, constantly battling their conservative opponents led by Khamenei, should come to an end.

Most likely, the 2021 presidential election will also lead to the victory of a radical conservative, at which point the project of shaping a “uniform ruling system” will be complete.

Constant friction

Against this backdrop, there is confusion about the political forces in Iran. Less than two months after the deadliest political unrest since the inception of the Islamic Republic, the funeral of Qassem Soleimani - the top commander of the Revolutionary Guards’ Quds Force, assassinated in a US strike - brought millions into the streets in Iran.

Some observers tried to argue that the participants in that massive funeral were not necessarily supportive of the government. One university professor argued that Soleimani was “a nationalist symbol who helped repel the Iraqi invasion in the 1980s and stand up to US aggression since then”. The reality is that Soleimani’s name began to be spread around after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. During the Iraq war his name was never heard.

Meanwhile, one of the points of constant friction between the domestic opposition and radicals in Iran is the hostile position that the deep state has towards the US. Soleimani’s radical anti-US worldview would not make him a national hero, popular among all political segments of society. It would definitely not attract those who are opposed to the system. He would also hardly remain above factional conflicts in Iran, having identified himself as the “child and soldier” of Khamenei.

So it is safe to argue that the overwhelming majority of those who left their homes on a national holiday to go into the streets to display respect to a general who was the symbol of war against US hegemony in the region - from Afghanistan, to Iraq, to Syria, to Lebanon - were supporters of the government. The question, however, is what percentage of society they represent.

Shortly after Soleimani’s death, the downing of a Ukrainian passenger plane and the deaths of all 176 people on board brought angry protesters into the streets of the capital, demanding accountability after officials initially concealed the cause of the crash. Khamenei argued that those who participated in the protests were “a few hundred” compared to the “massive crowd” that turned out for the funeral of Soleimani.

What he ignored was that if people were not killed during protests, as they were in November, and those opposing the system could freely take to the streets, the comparison would be more realistic and objective.

Power struggles

The bottom line is that Iranian society is fragmented into two hostile factions. The crisis in Iran is the result of a growing and intensifying conflict between conservatism and modernism. While the basis of this conflict is the different worldviews of these groups, the larger problem is that the conservative power structure and its supporters coerce the other portion of society into viewing the world as they do, and accepting the values that they believe in.

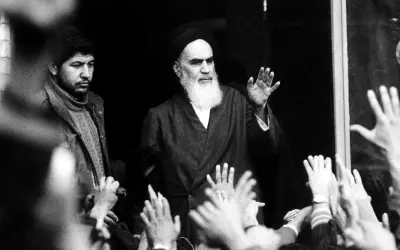

This is not a new development. Iran has been the stage of power struggles between two large factions, modernists and conservatives, for the last century. Under Mohammad Reza Shah, who was overthrown by the 1979 revolution, and, before him, during the rule of his father Reza Shah, modernists monopolised power. The 1979 Islamic Revolution reversed the balance of power, and conservatives led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini consolidated power exclusively for their camp.

There is no doubt, as mentioned earlier, that the priority for the deep state is to get rid of the “dual ruling system”. But at the same time, a low turnout in the upcoming elections would seriously call the legitimacy of the system into question.

To answer the question on the percentage that supporters of the system represent, a recent survey by the Iranian Students Polling Agency (ISPA), a polling center affiliated to the Academic Center for Education, Culture and Research (ACECR), could be helpful. The survey, which was conducted in Tehran, showed that in Tehran, just 21 percent of respondents said they would vote in the upcoming elections, while 55 percent said they did not trust that the upcoming election would be fair. Additionally, 75 percent of respondents believed that the November protesters, hundreds of whom were killed in the crackdown and thousands more put behind bars, were right.

Low voter turnout

In a speech earlier this month, Khamenei acknowledged: “Some may not favour me.” Then, playing the patriotism card, he used terms never heard from him before: “Anyone who likes dear Iran, the security of the home country and the prestige of the fatherland, has to show up at the ballot box.”

In the last two years, Iran has faced crisis after crisis, significantly damaging the legitimacy of the system. There is no doubt that low voter turnout will further damage the deep state’s claims about the popularity of the system.

Given the deep state’s decision to shape a uniform ruling system - and with the country caught in a wretched economic crisis caused by sanctions, widespread corruption and mismanagement - there is nothing that can reverse the current trend of the system distancing itself from the people.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].