'The game': The gamble Bangladeshis take in Libya to reach Europe

Sixteen hours had passed since the boat that Jakir* had boarded in darkness and in silence had run out of fuel. Stuck now on a crowded wooden vessel that bobbed helplessly at the mercy of the Mediterranean’s changeable temper, the 27-year-old was no closer to his goal of reaching Italy.

Jakir had lost what Bangladeshis call “the game” - the gamble taken with their lives when traffickers herd dozens of them onto a small fishing boat off the Libyan coast and point them towards Europe.

Back in his home village, he told the story in a room of other young men who had tried similar journeys or knew others who had.

Everyone knew about the game.

Families in this village have seen hundreds of attempted journeys to Europe through Libya in the past few years. The same is true across Bangladesh's northeastern district of Sylhet, from where many leverage a large diaspora to pay traffickers' fees.

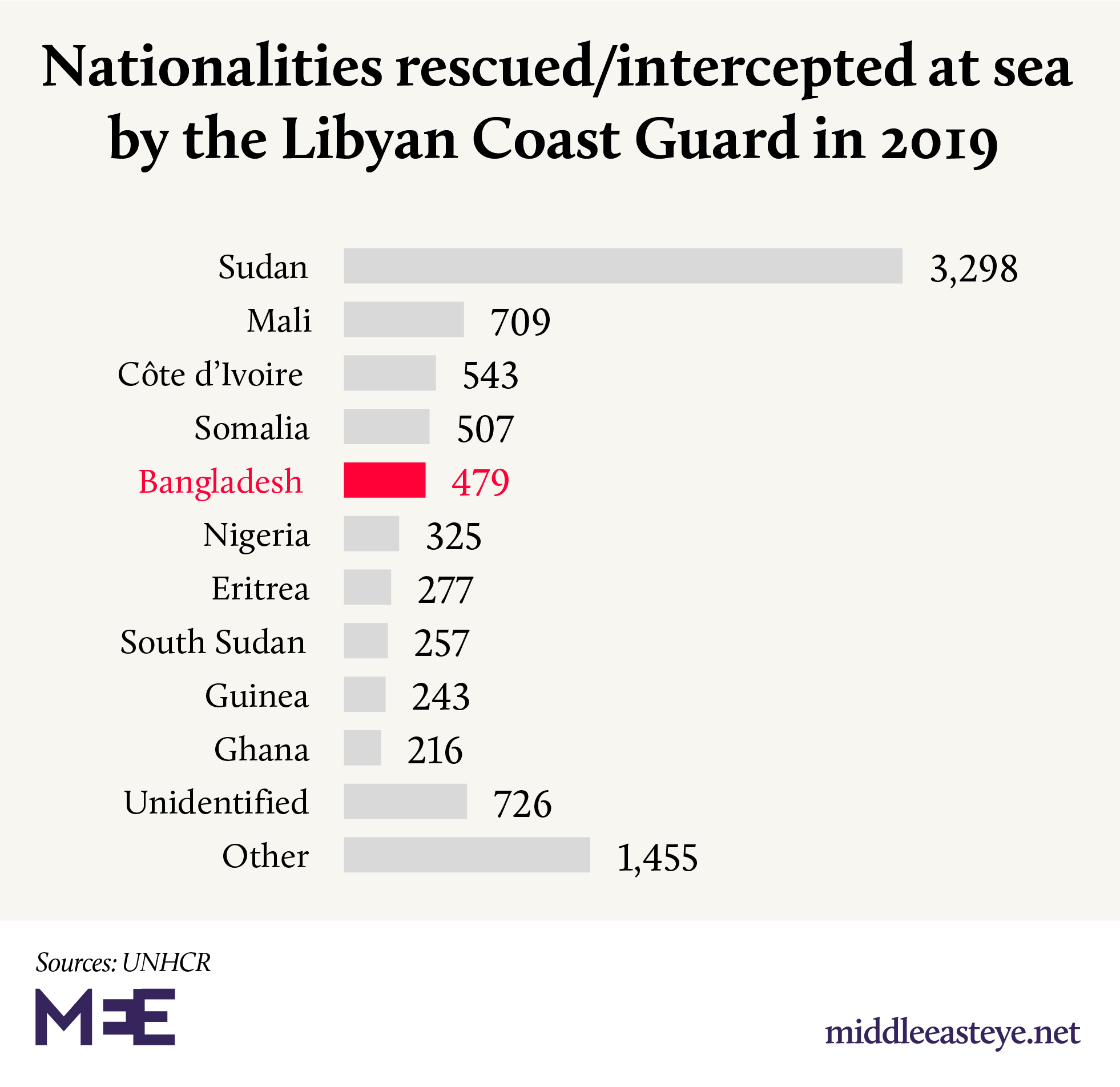

Set on halting migration to its shores, Europe has heavily invested in stopping these boats and turning them back, despite the dangers they are likely to face at sea. Bangladeshis, however, still continue to make the long and arduous journey to Libya, now one of the largest nationality groups trying to cross the Mediterranean.

According to the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, Bangladeshis were the only non-African nationality in the top 10 intercepted at sea during 2019.

Dreams of Europe are stoked by friends and relatives who have made it with the help of brokers, known as dalaals, who organise the journey with stopovers in Turkey or Tunisia.

“If anyone I knew told me they wanted to do it, I’d tell them they are crazy and offer to lock them up in a small room here so they can get the experience themselves,” Jakir, who is now back in Bangladesh after spending months in Libya last year, told Middle East Eye.

His first two months were relatively comfortable. He stayed in accommodation organised by the dalaal as he awaited his turn to cross. But shortly before his time came, he was transferred to what the Bangladeshis in Libya call “the game house”.

There, conditions changed.

Deception

Somewhere outside the capital Tripoli, they were held in the dark and given barely any food, which, Jakir said, was to make them lose weight before they made the journey.

Suddenly, one day, they were transferred to another location before being taken at night to the coast.

He had been told they would be crossing to Europe on a fishing trawler, but the armed men standing behind the gathering migrants, mostly from African countries, forced them onto a much smaller boat. They were given no food and one person in the group was assigned captain.

The designated captain was told to follow a compass to Europe and ask for help if any larger boats passed.

Once at sea, things took a turn for the worst.

'They [Libyan militias] put us through all kinds of mental and physical pain'

- Jakir, Bangladeshi migrant

Even after their fuel ran out, passing ships refused to help the increasingly desperate passengers, who included a pregnant woman. They were eventually rescued by a Libyan coastguard boat and transferred back to land, where they were kept in detention centres run by Libyan militias.

Jakir said that this was where he faced the worst treatment.

The migrants were often denied food by the militias, who also confiscated blankets given to them by the UN’s migration agency IOM. Jakir said some migrants accepted work offered by the militias and went off, only to never be seen again. Their families would later receive phone calls demanding ransoms.

“Libya for Bangladeshi people was full of problems,” Jakir said. “They put us through all kinds of mental and physical pain.”

Stories of crushed dreams and tragedies return to Bangladesh with those who lost the game, but these accounts compete with the success stories of those who made it to Europe.

The promise of Europe

Faruk*, 23, knew there were “hundreds and hundreds of risks” that came with boarding a rubber dinghy to cross the Mediterranean, but he, and even his mother, felt the promise of Europe was worth it. But they had almost no knowledge of the civil war that has been raging in Libya for several years.

“There’s a chance to earn money there [in Europe], to get a livelihood. From Italy you can travel by road and reach France. There’s a chance to settle,” he said.

His brother-in-law had managed exactly that.

Ultimately, Faruk did not get further than Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, where after more than a week of waiting, the dalaal broke off the deal. He later tried a different tactic by flying to Oman, where he worked for a few months hoping he could save up enough to muddle his way through Iran and Turkey.

His plan failed, however, as he was not able to save the money needed to make his trip.

At least half a million Bangladeshis leave the country for work every year, sending back $15bn in remittances.

Many left Bangladesh for Europe in the 1960s, but as immigration laws tightened, later generations sought opportunities in Saudi Arabia instead.

But even in the Gulf, which relies heavily on migrant labour, Bangladeshis have been subject to immigration raids, leading many workers to veer towards irregular routes.

Tens of thousands had travelled by boat to Malaysia, alongside Rohingya refugees from Myanmar, until in 2015 mass graves were discovered along the route in camps run by smugglers.

Today, many aim for Europe.

Dalaals

Bangladesh was one of the poorest countries in the world when it gained independence in 1971, but it now has a fast-growing economy that will soon see it become a middle-income country.

But the growth has been unequal, concentrated in the hands of rich businessmen in certain sectors, such as the garment industry. The country has seen a rapid rise of the super-rich, while most of the population is left behind.

“What is there here? There’s so little for us here. I have a sister with a master's degree and she’s spent half her life searching for a job," Jakir said.

"We don’t have any future here, there’s no security."

Dalaals in Bangladesh offer a way out towards a better life. While they advertise journeys organised illegally, there's also a legitimate side to their business, which includes organising passports and permits to Malaysia or the Middle East.

Though many of these trips end in failure - whether because of the lack of work for men or the abuse, or even death, of women employed as maids - the dalaals operate fairly freely and often do not have to do much work to recruit young people.

“It’s not hard to find a dalaal. Everyone knows someone, somewhere and it’s easy for them to spread their message,” said Faruk.

A distant relative organised Faruk's trip to Oman. Relatives also organised Jakir's trip to Libya, as did the relatives of friends he travelled with.

With so few opportunities in rural Bangladesh, the dreams sold by friends and relatives made the idea of escaping more promising.

“We are always on the lookout for an opportunity,” said Faruk.

*All names changed to protect their identities

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].