Egypt: Seven years after the coup, repression reigns as the economy tanks

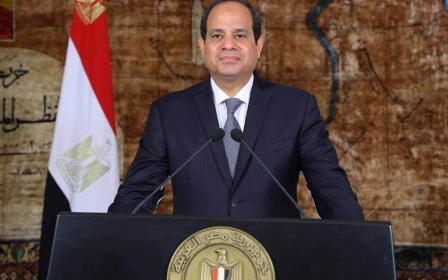

Egyptians who demonstrated in support of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s coup in the summer of 2013 likely expected, at a minimum, increased political freedom and an improved economic situation.

Seven years later, it is clear that demonstrators did not get what they hoped for.

Today, Egypt is more repressive and worse off economically than it was under Mohamed Morsi, the nation’s first democratically elected president, ousted by Sisi just a year into his first term in office.

A protest law that criminalises anti-government demonstrations has helped the state to imprison tens of thousands of people

Military coups almost never lead to greater levels of political freedom, democracy or human rights. Egypt offers a textbook illustration.

Although the one-year Morsi period wasn’t necessarily a model of democratic perfection, it was relatively open, free and competitive, particularly when compared with the current political climate.

The Sisi regime began its reign by promptly rolling back nearly all of the gains accrued after Egypt’s 2011 democratic uprising, including those advanced by Morsi during his brief stint in office.

The post-coup regime, led by Sisi, immediately shut down opposition media outlets, arrested political leaders, banned leading political parties, and carried out several massacres against protesters. The 14 August 2013 massacres at Cairo’s Rabaa and Nahda squares may constitute the largest single-day slaughter of protesters in modern world history.

Importantly, the post-coup government also passed draconian legislation. A protest law that criminalises anti-government demonstrations has helped the state to imprison tens of thousands of people. Egypt currently holds more than 60,000 political prisoners.

Given the protest law and the broader climate of fear that has enveloped Egypt, it is perhaps unsurprising that Egyptians aren’t participating in ongoing, global Black Lives Matter protests. While there are undoubtedly many Egyptians opposed to police brutality and anti-Black racism, the Sisi government’s history of anti-protester violence, along with its oppressive legal framework, have effectively eliminated any possibility of protest.

Silencing of journalists

The Sisi regime has also succeeded in fostering a singular, pro-regime media narrative. This has been achieved through both the aforementioned media closures and a broader campaign of strong-armed intimidation.

In particular, Sisi has used Egypt’s press law, penal code, new constitution, and new anti-terror law to silence critical journalists, with articles allowing the government to censor, fine and arrest journalists, particularly on issues relating to Egyptian “national security”. Today, Egypt is the world’s third-worst jailer of journalists.

In 2019, the government blocked tens of thousands of website domains set up to oppose government-proposed constitutional amendments allowing Sisi to extend his rule through 2030.

Earlier this month, the government announced censorship on news coverage of “sensitive” issues, including the coronavirus pandemic, the conflict in Libya, the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) and the Sinai insurgency.

The government also recently arrested journalist Mohamed Mounir over his coverage of the Covid-19 crisis, and relatives of Mohamed Soltan, a prominent human rights defender who writes critically of the regime from his home in the US. Last week, Nora Younis, editor of al-Manassa news website, was briefly arrested after police raided the outlet’s offices and searched its computers.

Meanwhile, pro-Sisi Egyptian media have used the 25 May murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis to deflect blame from brutal Egyptian police and subtly justify their history of violence. Broadcast journalists on pro-government channels have suggested that if police violence is an inevitability in the US, which claims to be governed by democratic norms and the rule of law, it should also be expected in a place like Egypt.

Economic regression

At the same time, Sisi’s major economic projects, including a new capital city and a massive Suez Canal expansion have, so far, been unsuccessful.

Sisi projected the August 2014 canal expansion to more than double annual revenues, from $5.5bn in 2014 to $13.5bn by 2023. Instead, canal revenues have either declined or increased only slightly in each year following the expansion. In 2018/19, revenues were $5.8bn, far below projections.

The Egyptian pound has been devalued from 7.1 per dollar in June 2013 to 16.1 per dollar today. Egypt’s main economic programme under Sisi has been to borrow tens of billions of dollars from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, China and allies in the Persian Gulf, among other sources.

Egypt’s national debt has nearly tripled since 2014, from about $112bn to about $321bn. This week, Egypt secured an additional $5.2bn loan from the IMF. Nearly 40 percent of Egypt’s annual budget is devoted to paying off interest on loans.

Loans have enabled the government to boost foreign reserves and other macroeconomic indicators, but microlevel economic indicators suggest that the average Egyptian is struggling mightily.

The price of basic goods has increased dramatically since Sisi took power, and in particular since the launch of the IMF loan programme in late 2016. The IMF required the regime to slash government subsidies on essential goods.

Subordinate allyship

Overall, the country’s poverty rate has increased from 26 percent in 2013 to 33 percent in 2018. According to a 2019 World Bank report, about 60 percent of Egyptians are either “poor or vulnerable”.

Sisi has also received billions of dollars in grants from the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. These grants have come at a great cost, leaving Egypt beholden to both nations.

UAE and Saudi grants have come at a great cost, leaving Egypt beholden to both nations

In 2016, Egypt handed over two Egyptian islands to Saudi Arabia, and Egypt continues to do the foreign policy bidding of both the Saudis and the Emiratis.

Earlier this month, Sisi threatened military action against Libya’s UN-recognised government. Unsurprisingly, his remarks were received favourably by both the UAE and Saudi Arabia, who have turned the money they’ve spent on Egypt into a relationship of subordinate allyship.

It’s possible that Sisi’s threat was issued with a multi-pronged purpose in mind: to appease his supervisors in Abu Dhabi and Riyadh, and to distract from his government’s gross mishandling of both the coronavirus pandemic and the GERD project.

What does the future hold?

It was difficult enough to make sense of hardline Morsi critics in 2013, when Egyptian liberals claimed, quite absurdly, that Egypt was witnessing a dictatorship more repressive than the one presided over by Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s dictator from 1981 to 2011. It is almost impossible now.

Indeed, the Morsi period now appears as a lost opportunity. Morsi was obviously not a perfect leader, but the political system enshrined by the post-2011 uprising and 2012 constitution would have allowed for political contestation, and, over the long haul, the breakup of Egypt’s deep state.

Egyptians critical of Morsi, who was killed while in jail last year, would have been better served by seeking to impeach Morsi through the 2012 constitution’s impeachment mechanism, or simply seeking to vote him out of office.

The weeks, months and years ahead under Sisi may prove even more difficult for Egyptians than the past seven have been. The nation has proven itself ill-equipped to handle the ongoing coronavirus crisis, and the ramifications of the GERD project could be far-reaching and devastating for Egypt, which depends on the Nile River for most of its water supply.

Ironically, Egypt’s only hope may be another popular uprising. The hope, for many Egyptians, is that the next popular protest movement leads to more democracy, and not more dictatorship.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].