Srebrenica, 25 years on: How genocide denial is adding to survivors' pain

Survivors of the Srebrenica genocide in Bosnia Herzegovina 25 years ago say they are enduring a double-edged nightmare due to a growing local culture of genocide denial, in which war criminals are celebrated and history is being rewritten.

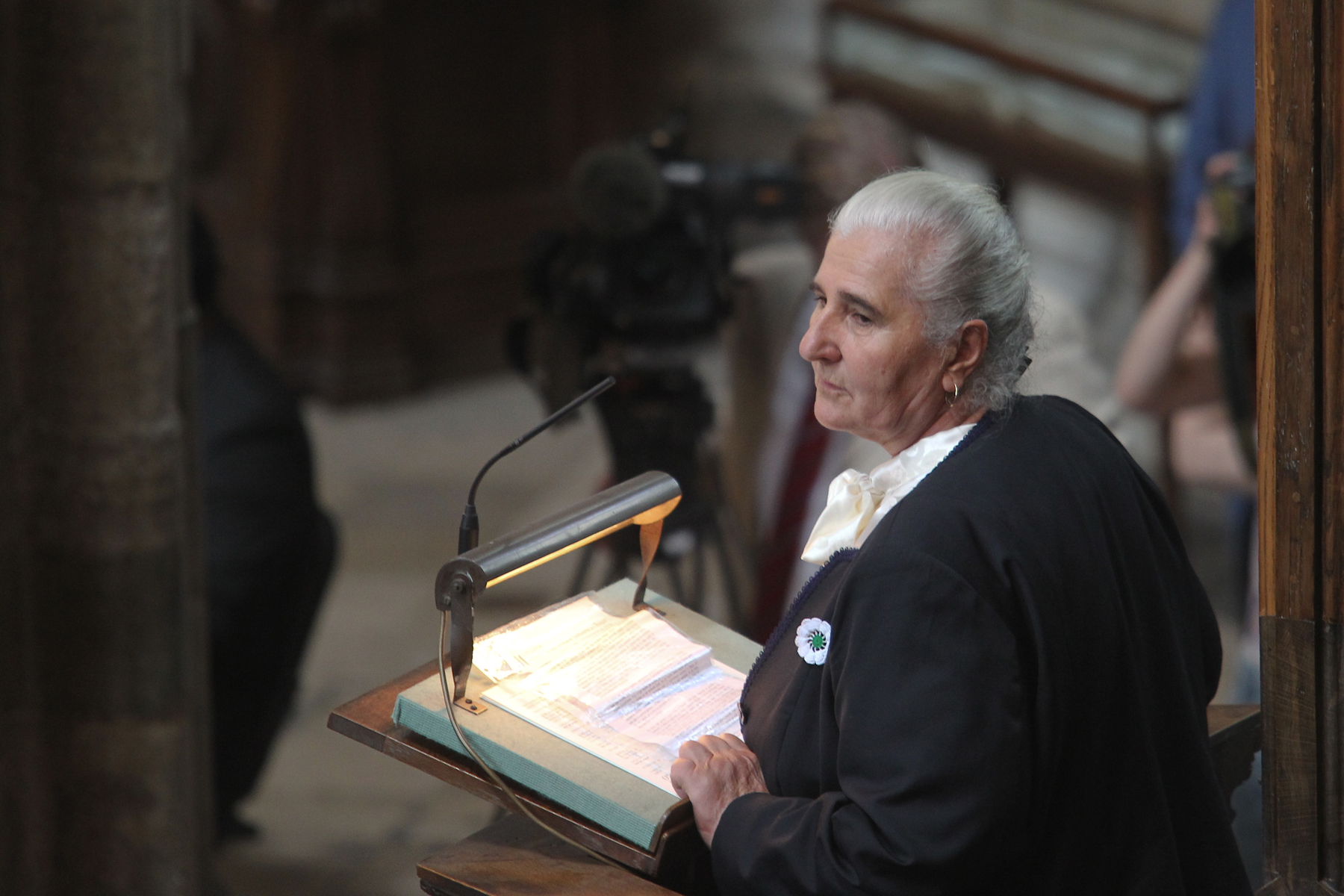

“It is unimaginably painful to be in Srebrenica,” Munira Subasic told Middle East Eye ahead of Saturday's anniversary of the fall of the formerly Muslim-majority town to Bosnian Serb forces.

Subasic is the president of the Mothers of Srebrenica organisation. She lost more than 20 family members in the Bosnian war, which followed the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

Srebrenica, in eastern Bosnia near the Serbian border, had been declared a safe area by the United Nations and was officially under the protection of UN peacekeepers, who surrendered the town to the Bosnian Serb army on 11 July 1995.

Over the next few days, more than 8,000 Bosnian men and boys were murdered.

Both of the main architects of the Bosnian Serbs' genocidal campaign, political leader Radovan Karadzic and military commander Ratko Mladic, are now serving life sentences for their crimes, arrested by Serbia after years in hiding and convicted by a UN war crimes tribunal at The Hague.

But survivors say they are being haunted by those who tried to kill them or drive them away from their homes, many of whom they still see on the streets of the town and who have never faced justice. Some, they say, have gained positions of authority on the local council and in the local police force.

“We are faced with injustice and denial almost on a daily basis, even though we are on our land. We get looks that make us feel that they want us to be dead as well,” said Subasic.

“Genocide denial is killing us again. It is an additional phase of genocide because... the genocidal plan never ended. Srebrenica is a living genocide and it is denied just like the killings of our loved ones were denied.”

General Mladic Street

For the past quarter century, Srebrenica has been under the control of Republika Srpska, the Bosnian Serb-controlled entity that was recognised as part of a federal Bosnia Herzegovina in the peace deal that ended the war later in 1995.

About 14 percent of the population of Republika Srpska is Muslim, according to the last census.

Many local schools segregate Muslim and Serb children, while teaching of the genocide was removed from the curriculum in 2017.

Meanwhile, Bosnian Serb war criminals and their allies at the time of the conflict are being honoured with street names, buildings and statues.

In the village of Pale, which is in the Srebrenica municipality, there is now a Radovan Karadzic Student Residence, named after the former Bosnian Serb political leader.

In Bozanovici, there is General Mladic Street, dedicated to the Bosnian Serb military commander who was born in the village.

In 2018, Republika Srpska erected a statue of Vitaly Churkin, the former Russian ambassador to the UN who vetoed a resolution condemning the killings in Srebrenica as genocide.

Republika Srpska is not alone in the region in honouring figures accused or convicted of war crimes. An investigation by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network in May also found examples of a street in a Croat-majority Bosnian town named after a Croat general accused over the killings of at least 100 Serb civilians, and a mosque honouring a Bosnian Army general accused over the killings of 34 captive Bosnian Croat soldiers and civilians.

But with most of Srebrenica's historic Muslim population having either been killed or forced to leave the town, campaigners warn that genocide denial is in the ascendancy.

“Denial strategy started slowly with the funding of small NGOs and academics who were tasked with discrediting the internationally accepted truth of events. Now it is a state policy,” Hikmet Karcic, an academic and researcher on genocide based in Sarajevo, told MEE.

Denial among Bosnian Serb figures of authority goes to the very top.

Srebrenica's mayor, Mladen Grujicic, has denied that the killings that took place constituted genocide, as they have been repeatedly recognised in international law.

“When they prove it to be the truth, I’ll be the first to accept it,” he has said.

Ramiza Gurdic, who lost two sons in the genocide and still lives in Srebrenica, told MEE: “So much has changed but in reality nothing has changed. It is painful because it reminds me of everything. I still have not entered the municipality building since Grujicic was elected.”

Milorad Dodik, the Serb member of the joint-presidency of Bosnia Herzegovina, called the genocide a “fabricated myth” only last year.

Documented atrocity

Yet Srebrenica is perhaps the most well-documented atrocity of its kind in history.

After the fall of the town to the Bosnian Serbs, thousands fled to the nearby village of Potocari, where around 200 Dutch UN peacekeepers were stationed.

Faced with the Bosnian Serb army and with no support from the international community, the peacekeepers withdrew.

On 12 July, executions and evacuations of men and boys to killing sites began. Meanwhile, thousands of women and girls suffered sexual assault. By the end, more than 8,000 had been killed.

Details about these events are known because of painstaking efforts to identify the bodies of the dead. The International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) was created in 1996 in response to the conflicts in the former Yugoslavia.

Since then, almost 90 percent of the Srebrenica victims have been identified.

“That’s unprecedented,” said Kathryne Bomberger, director-general of the ICMP.

For some, however, the long wait for confirmation of the fate of missing relatives continues.

“I am still searching for the remains of my loved ones,” said Ramiza Gurdic. She tells a story that is common among the women survivors. It is one of watching husbands and sons marched into the forest.

“My Mustafa was born in 1975 and Mehrudin in 1977. I am still searching for Mehrudin's skull to be found and identified from mass graves. It's not easy remembering how both of them left with their father, my husband, to go through the forest and never seeing them again,” she said.

Bomberger describes how the perpetrators of the genocide tried to cover up their crimes, using bulldozers to move bodies to different locations across eastern Bosnia.

“It was common for the body of a victim of the genocide to be found in anywhere from five to 11 different locations sometimes 50 kilometres apart from each other. That's how extensive the cover up was,” she said.

The scale of the challenge led to the pioneering use of DNA identification of the victims whose bodies had been mutilated and dismembered.

“The evidence that has now been provided is irrefutable. It’s scientific. It’s been subject to rigorous court proceedings. To deny these events is ludicrous and dangerous,” Bomberger told MEE.

European inaction

This makes it all the more extraordinary that the events at Srebrenica 25 years ago are being largely ignored.

In 2009, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on Srebrenica calling "on the Council and the Commission to commemorate appropriately the anniversary of the Srebrenica-Potocari act of genocide by supporting Parliament's recognition of 11 July as the day of commemoration of the Srebrenica genocide all over the EU, and to call on all the countries of the western Balkans to do the same."

But Waqar Azmi, founder and chairman of the Remembering Srebrenica campaign, told MEE that despite two EU resolutions calling for member states to commemorate Srebrenica Memorial Day on 11 July each year, “only Britain holds a national commemoration or has developed educational programmes”.

'It's not easy remembering how both of them left with their father, my husband, to go through the forest and never seeing them again'

- Ramiza Gurdic, survivor

For Azmi, this lack of effort to commemorate and educate by other EU member states is “deeply shameful”.

“It is also deeply worrying that this inaction on the part of [European countries] is emboldening those seeking to deny the genocide whilst glorifying the architects of the genocide,” he added.

The reluctance of EU states to adequately remember the Bosnian genocide may point to unease surrounding their own conduct at the time.

According to The Clinton Tapes, an account by Taylor Branch of Bill Clinton's presidency based on recorded conversations with its subject, the US president believed European leaders were prejudiced against Bosnia Herzegovina on account of its Muslim-majority population.

Clinton is reported as saying that European allies constantly blocked proposals to adjust or remove the arms embargo imposed on Bosnia because "an independent Bosnia would be 'unnatural' as the only Muslim nation in Europe”.

“[Clinton] said President Francois Mitterrand of France had been especially blunt in saying that Bosnia did not belong, and that British officials spoke of a painful but realistic restoration of Christian Europe," wrote Branch.

This attitude was reflected in comments by Boris Johnson, now the British prime minister but then a journalist, who wrote in the Daily Telegraph in 1997: “All right, I say, the fate of Srebrenica was appalling. But they weren’t exactly angels, these Muslims.”

In a message posted on the Remembering Srebrenica website in 2018, when he was foreign secretary, Johnson described the genocide as "one of the worst crimes in Europe’s modern history".

Recently declassified British government office documents reveal distrust and disagreement between the UK and France, both United Nations Security Council permanent members, about how to respond to the situation.

British officials accused French President Jacques Chirac, who had replaced Mitterrand in May 1995, of “lunacy” and “grandstanding”, and also suggested that France may have made a secret deal with the Bosnian Serbs to halt air strikes in return for the release of peacekeeping troops being held hostage.

British officials also sought to limit military involvement in Bosnia and resisted pressure from Washington for more air strikes targeting Bosnian Serb forces in the aftermath of the fall of Srebrenica.

One senior official advised that British peacekeepers should be withdrawn from the final Bosnian Muslim safe area of Gorazde, which was facing imminent attack, to avoid being sucked into the war.

These are new details for historical accounts of how western powers failed the victims of Srebrenica. But the official added: “We must not allow ourselves to be identified as a country responsible for ‘the defeat of Bosnia’ (implications for our trading position etc in the Arab world).”

Yet the Bosnian genocide has become a reference point for contemporary far-right ideology and an inspiration for its most violent advocates.

The perpetrators of last year's attack on a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand, in which 51 people died, and a 2011 far right-inspired attack in Norway in which 77 people died, both took inspiration from the Serbian ultra-nationalist cause of the 1990s.

Munira Subasic told MEE that campaigners were seeking “truth and justice, not revenge”.

“The day when I last saw my loved ones, my son, husband and close relatives, is a day when a part of me was killed as well. I remember every detail,” she said.

“As a living survivor and a witness, I carry the burden of seeking truth, because it is the only way to prevent the Srebrenica genocide from happening again. As a mother, I am still screaming for justice.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].