Caught between fact and fiction: How Palestinian authors write about their cities

How do you write about a city you’ve never seen? How do you reconcile a long-imagined city with the one that suddenly appears in reality? And how do you describe a city that is constantly telling you that you don’t belong?

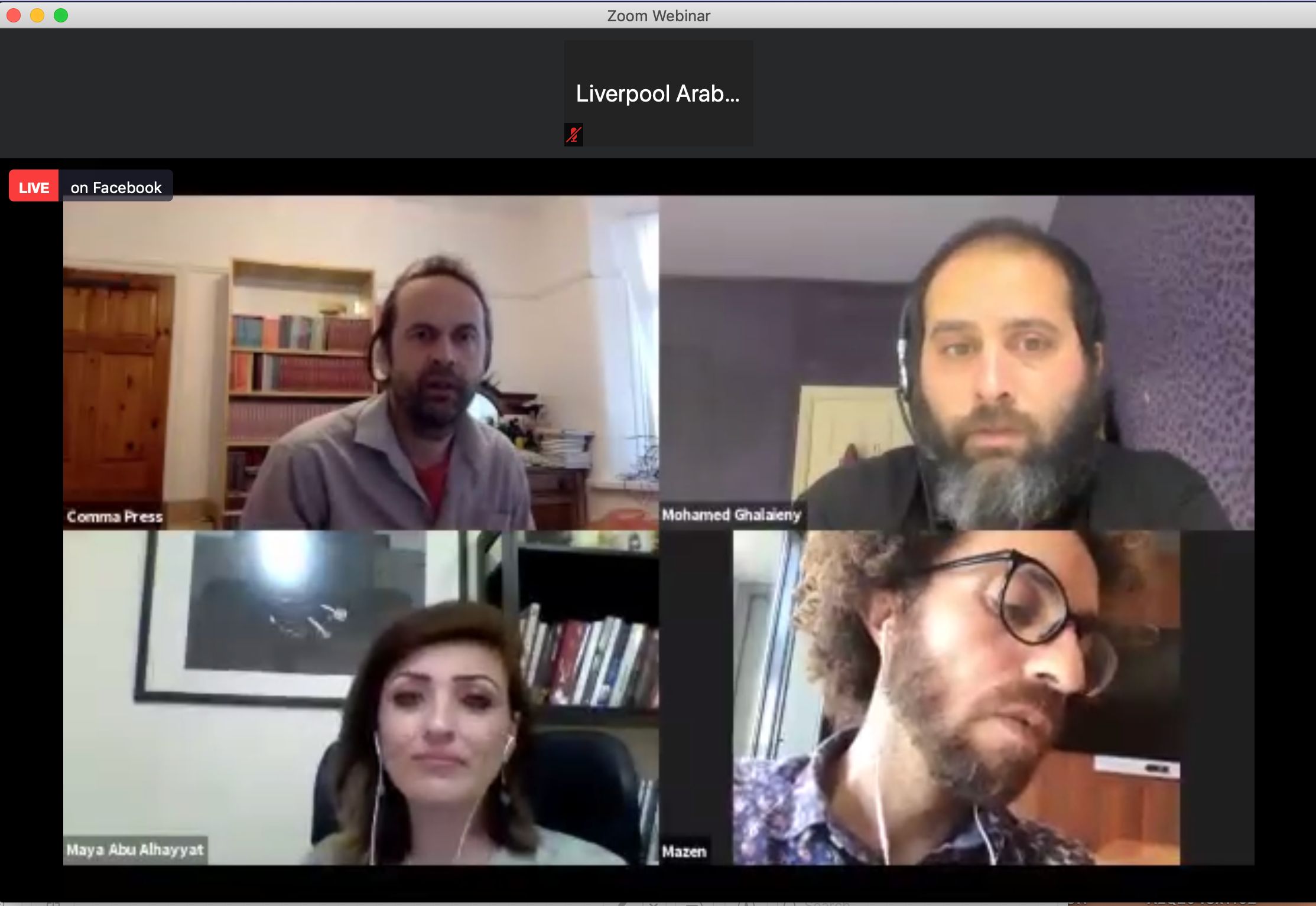

These were some of the challenges addressed by award-winning Palestinian writers Maya Abu al-Hayat, Mazen Maarouf, and Talal Abu Shawish at Writing the Palestinian City, held as part of this year’s digital Liverpool Arab Arts Festival (LAAF). The 13 July talk took place over Zoom, one of several literary panels that formed part of the LAAF festival, forced to go online in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Chaired and introduced by Ra Page of Comma Press - which published Palestine + 100 and The Book of Gaza, and will soon publish The Book of Ramallah - the panel was also joined by interpreter and translator Mohammed Ghaleiny. Readings by Ghaleiny, Abu al-Hayat, and Maarouf were followed by an incisive, thoughtful discussion about constructing and deconstructing literary cities, and the clash between a reality and an author’s imagination.

LAAF, the UK’s longest-running annual festival of Arab culture, kicked off 9 July and is set to close on the 18th. While the festival is ordinarily held at art galleries, theatres, cinemas, and concert halls around Liverpool, most of these UK venues are now shut in response to the global public-health crisis. Like numerous other arts organisations, several months ago LAAF organisers made the decision to adapt their festival for online audiences.

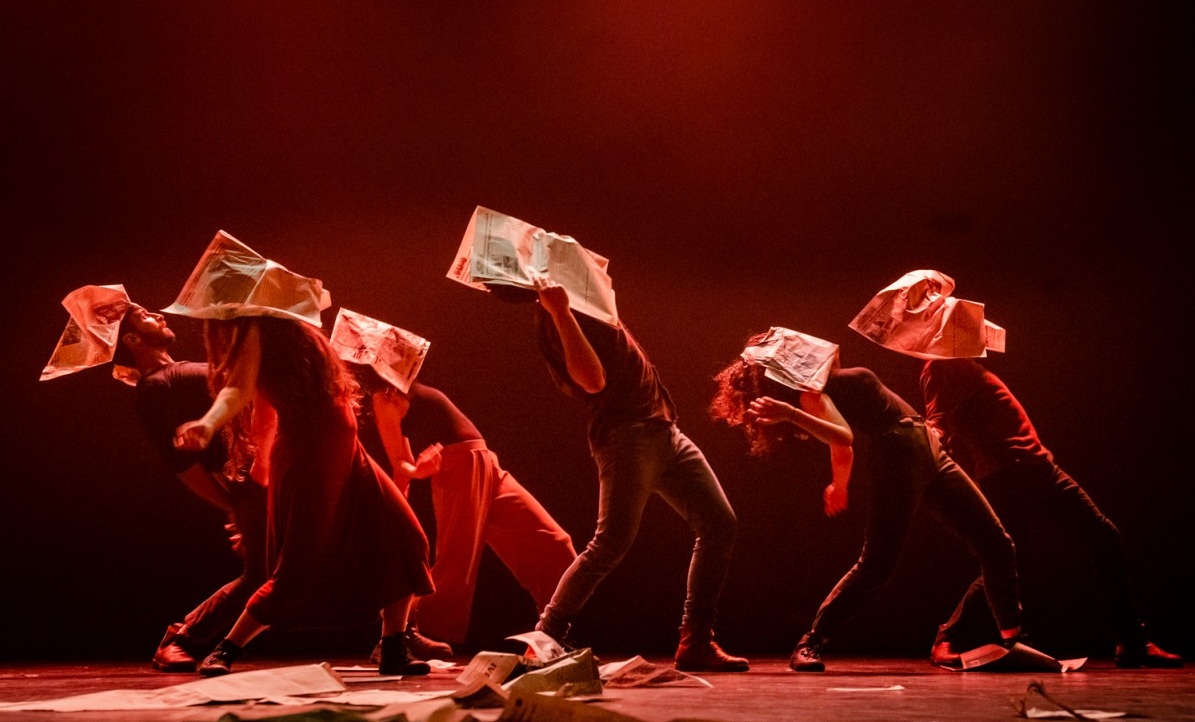

In addition to being “attended” online rather than in person, this year’s LAAF is much less performance-oriented than in the past. Instead, they shifted toward talks with artists, authors, and musicians that work better online.

This year, you can’t attend a dance performance in Liverpool. But you can watch a discussion amongst members of Hawiyya Dance Company and El-Funoun Palestinian Popular Dance Troupe about what dabke means to them.

Author events were perhaps the easiest to move online. And while those who attended Writing the Palestinian City on Zoom missed out on seeing the authors in person and picking up new books, there was a large upside: the three authors spoke from Gaza, Jerusalem, and Reykjavik, and audience members also logged in from around the world.

Each author took a markedly different approach to writing about cities: Talal Abu Shawish, who grew up in Nuseirat Refugee Camp and moved to Gaza City, talked about his story Red Lights, translated by Alice Guthrie, which focuses on small, charitable acts that can make a large difference in a difficult city.

In the story, children selling tissues, chocolates, and windscreen-cleaning services seem to surround a taxi driver as he attempts to move through a crowded streetscape.

Maya Abu Al-Hayat read a short personal essay set around Nablus and Ramallah, My Vertical City and My Horizontal Escape, translated by Ghaleiny, which is built around her shifting relationship to the Nablus cityscape. And Mazen Maarouf read an excerpt from his surreal Jokes for the Gunmen, translated by Jonathan Wright, which is set in a brutal and violent city that goes unnamed.

The imagined Palestinian city

Maarouf, who writes both poetry and prose, is a second-generation refugee. His family had to flee Tal El-Zaatar refugee camp at the start of the Lebanese civil war, and he grew up in Beirut. His first short-story collection, Jokes for the Gunmen, was translated to English by Jonathan Wright and longlisted for the Man Booker International.

The city in the title story, Jokes for the Gunmen, seems like an off-kilter version of Civil War-era Beirut. The section Maarouf read opens: “At school the kids competed with each other by telling stories about how their fathers beat them.”

Each boy wants his father to be the most violent, the most terrifying, but the narrator’s father isn’t scary at all. His role is to make jokes for the local militiamen. If the jokes aren’t funny, then they beat him.

But throughout the story, the city is never given a name. Ra Page asked why.

From the time he was born, Maarouf replied, he was “not allowed to consider Beirut my city”. Instead, he belonged to a Palestine that he could only imagine. As he walked around the real streets of Beirut, he was also walking around an imaginary Palestine in his mind.

“At some point, identity-wise, I was living in a fictional city while I was practising my daily life in a city that reminded me, every day, that this is not your place.”

In Jokes for the Gunmen, leaving the city unnamed means it’s at a remove from the characters. They are part of the cityscape, and yet they are not.

Chasing ghosts in Nablus

In Abu al-Hayat’s My Vertical City and My Horizontal Escape, Nablus also starts out as an imaginary place. Abu al-Hayat was born in Beirut and grew up partly in Tunis, listening to her father’s reminisces about Nablus. He was, she writes, “obsessed with the dishes and delicacies of the city. We would go from one Lebanese restaurant to the next so he could find somewhere to eat knaffa, ojja, or zalabya. All of these were now associated, in my head, with that legendary place that made weird and wonderful desserts we couldn’t find anywhere else.”

When Abu al-Hayat finally moved to Nablus, she was confronted by a city that was very different from the one she’d imagined. “My Nablus was all about myths and stories of the Old City, mystical beings and ghosts, the Yasmina neighbourhood and the onion market.”

Whereas the real city was full of hard edges, tall mountains, and a world that was so “vertical” she could only look up and down, at the heavens and the ground. She had to leave the city, she said, to be able to see the horizon.

During her talk, Abu al-Hayat spoke of how difficult it was to find herself in Nablus. In the end, she moved to Ramallah, a more “horizontal” city, with vistas that look out into the distance.

“When you’re in Ramallah, you’re not living in the City of Ramallah, you are escaping to Ramallah,” she said during the talk. “It’s not a city and it’s not a village, and at the same time everything is happening there. It can give you a space to experiment,” she said, with less judgment than in Nablus.

But at the same time, because there are few who are native to Ramallah, she said, “it’s everybody’s city. Which is good.”

Abu al-Hayat currently lives in Jerusalem, with her husband and children, and works in Ramallah. Jerusalem is yet a different sort of city life, one of impermanence, where Abu al-Hayat says she doesn’t know if her residence permit will be renewed from year to year.

“When I say now that I live in Jerusalem, I always say I live at the checkpoints. I’m not living in the city of Jerusalem - I’m living at Qalandia checkpoint.”

Location, location, location

Most of the discussion was about the authors’ own relationship with their writing and their cities. But Abu Al-Hayat is also the director of the Palestine Writing Workshop and editor of the forthcoming short-story anthology The Book of Ramallah, coming from Comma Press in 2021, and she wanted to talk about other authors’ depictions of Ramallah.

She was surprised, she said, that most of the submitted stories take place outdoors, on Ramallah’s streets. She had a harder time finding stories that took place inside individual homes. “And it’s rare for Palestinian writers to think about the house,” she said. “It’s always like your city itself is the house, because it takes on so much of your energy and your identity.”

Like the stories Abu al-Hayat describes, Talal Abu Shawish’s Red Lights takes place out on the streets, in the crowds of the city. But he said his next book will focus on the cityscapes inside the school where he works as an assistant director. “In the last ten years, I’ve gathered material for four hundred short stories from the school. I’ve written these as drafts, and I hope to make these my next project for publication.”

Abu al-Hayat also said that Arab and international readers can come to a story with very strong expectations of what they want to read about Gaza, Jerusalem, and Ramallah. Readers, she said, have expectations about what life is like in Palestinian cities.

“They already want to read something specific about the city. But you want, as a writer, to take them on a new journey… I want them to see the real Ramallah: the real isolation, the real fear, the real life.”

In describing the collection, Abu al-Hayat and Comma Press call Ramallah “a city of countless contradictions; defiant in its resistance against the occupying forces, but frustrated and divided by its own secrets and conservatism. Characters fall in love, have affairs, poke fun at the heavy military presence, but also see their aspirations cut short, their lives eaten into, their morale beaten down by the daily humiliations of the conflict.”

Maarouf also noted that literary cities are constantly changing, much as human relationships with urban spaces are also changing. The evening’s event, for instance, took place between multiple cities, and he can now find YouTube videos and photos of Palestinian cities online. But this reality also clashes with his imagined Palestine.

“So the fictional place is not entirely fictional. But it’s not entirely real, because I haven’t experienced it myself.”

To read depictions of Palestinian cities - past, current, and future - Comma Press has several city-focused books, including the future-fiction anthology Palestine + 100 which takes place in various cities in 2048.

The press’s “Reading the City” series also includes The Book of Gaza, edited by Atef Abu Saif. In 2021, they are set to publish The Book of Ramallah, which promises stories from well-known writers such as Ibrahim Nasrallah and Liana Badr, as well as several emerging writers who have made Ramallah their literal (and fictional) home.

Copyright for author photos: Jenny Hviding, Salim Abu Jabal and Talal Abu Shawish (Courtesy of LAAF)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].