REVEALED: The UK media company silencing Syrian activists on Facebook

A new tactic has been employed in the suppression of protests in Syria, with an opaque and obscure UK-based media company friendly to Bashar al-Assad’s government apparently forcing video footage of demonstrations from Facebook.

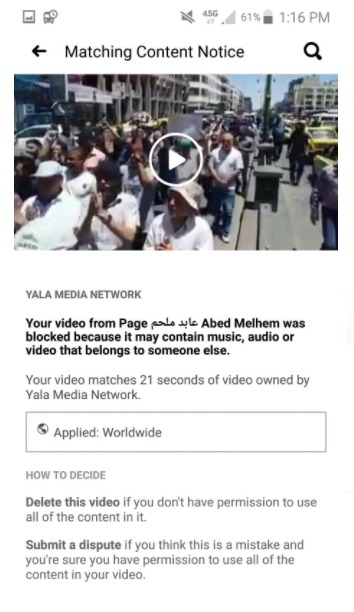

Several Syrian activists and citizen journalists have seen videos they uploaded to the social media platform of recent anti-government protests in the southwestern city of Sweida taken down due to alleged copyright infringement.

The rights to the clearly amateur footage taken by locally known activists and journalists, they were told, belonged to Yala Media Network, a mysterious company registered in London.

The Sweida protests in June, a rare show of public dissent in government-held areas, were pointedly absent from all Syrian state media reports. The government instead organised counter-demonstrations to shift the focus to the effect of harsh new US sanctions, and at least 11 protesters were arrested.

Activists suspect that the muzzling of grassroots footage from the protests is part of the government’s campaign to suppress any dissent.

Social media censorship and account takedowns in Syria are not novel.

Syrian activists as far back as 2014 have expressed horror at Facebook taking down videos of what they believe are clear evidence of human rights violations, abuses and even war crimes.

Just over the past two months, at least 35 Syrian activists and journalists have decried Facebook for deleting their personal accounts on the grounds that they have uploaded content that is violent, terror-related or does not meet the platform’s standards.

This time it is different, though, with supporters of the Syrian state believed to be using Facebook’s copyright policies as a way to directly target critical and independent voices.

Political leanings

At the centre of the Sweida trend is Yala Media Network.

Journalists and protesters were surprised to be told by Facebook last month that the video footage of Sweida’s anti-government demonstrations they had uploaded in fact belonged to Yala Media Network, an outlet few had heard of before.

Due to the claim of copyright ownership, the videos were either taken down, prevented from circulating, or even blocked from being uploaded altogether.

Yala describes itself on its Facebook page as a network that works on “television and music production through affiliate platforms or through cooperating partners”.

Although it has over 30,000 followers, it has had just miniscule interaction over its only two posts, including a promotion for a Ramadan television series.

Its financial information is unclear and the website of its parent company, Yala Group, mostly consists of dummy text, stock images and murky marketing jargon.

Although the company maintains that it is an independent Arabic media platform, it appears to have political leanings that favour the Syrian government.

Its content is primarily frothy skits and songs by mostly Syrian artists and actors, although ones such as Bashar Ismail, who have publicly expressed support for Assad and fiercely criticised those who stand in opposition to the government.

The address on Yala Media Network’s Facebook page leads to British Monomarks in central London, a company that provides a London mailbox and mailing address to businesses looking for a “prestigious London street address”.

Its parent company, Yala Group, is registered in the United Kingdom and also uses that same central London address.

The only person listed as working for Yala Group is Ahmad Moemna, identified as a United Arab Emirates-based Palestinian engineer born in June 1988, who is registered twice, as director and secretary.

Moemna runs at least two Facebook accounts, but both say he is based in Damascus. One has a profile picture of the Yala Group logo and shares few public posts other than a couple of generic pictures, including one of Assad in military garb.

His other profile is far more active, describing himself as a “manager” at Yala Group and originally from Aleppo. MEE could not verify whether he is of Palestinian origin or not.

There is no mention of the UAE, or employment as an engineer. Moemna describes himself as a social media advertiser and digital marketer.

The Facebook page also says that he is the business manager of another media organisation called Momento Media Network, which says it is based in Uppsala, Sweden.

Unlike Yala Group, Moemna has a picture of himself in an office with the Momento logo and a desk with his name on a placard. Although its website is not accessible, pages as recently as November 2019, via Wayback Machine, reveal that Momento Media Network primarily worked on increasing ad revenues for businesses through media services.

It also has an address in Malaysia, which matches a Malaysian-based company called Arabic Web Sdn Bhd, along with a Turkish phone number.

The Turkish phone number leads to a customer service worker. When asked if he was with Momento Media Network, he said he worked for Yala Group and that the former company “has different management”.

According to Momento Media Network’s Facebook page, it was launched in 2016. It includes some original videos and skits, although most of it is random viral videos and even reposted content from Yala Media Network.

Yala rejects allegations

When MEE contacted Yala Group through its London landline number, an individual claiming to be the company’s CEO responded.

Bassel, who declined to share his last name, told MEE that the company manages clients and produces its own content for a global Arabic-speaking audience. He added that they have branches in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates.

When asked about the Sweida protest videos, Bassel deflected responsibility away from Yala, saying that it may have been one of the many partners whose material is published on the platform that claimed ownership, rather than the company itself.

According to Bassel, Yala has more than 1,000 videos uploaded to its platform on a daily basis, alleging that the platform functions as a broker for clients. He said the network could not identify who might have claimed copyright on Yala’s behalf.

Bassel did not respond to further inquiries from MEE following the phone call.

Upon inspection, Bassel’s claim that hundreds of videos are uploaded daily seems dubious. Its YouTube channels host fewer than 100 videos, mainly skits and music videos, all unrelated to politics. Amateur footage of anti-Syrian government protests seem an odd fit.

'Unprecedented issue'

Activists and journalists have had to respond in different ways to ensure that their videos are successfully uploaded and circulated widely on various social media platforms.

Rayan Maarouf, editor-in-chief of citizen journalism platform Suwayda 24, said that as soon as they were notified of the copyright infringement, they immediately appealed the decision.

“This happened to us four or five times during the protest and each time we followed the same steps,” Maarouf told MEE.

'Copyright claims seem to be a new way to clamp down on freedom of expression and to suppress the dissemination of spreading videos of opposition or dissent'

- Oussama Jarrousse, Syrian researcher and cyber-security expert

According to Facebook, content that has been reported as a copyright violation may be taken down without prior notice.

However, not all protesters are familiar with Facebook’s copyright rules, let alone with the process to dispute and appeal the copyright restrictions.

“Many didn’t know they had the opportunity to dispute. They had a limited period of time to do so and were unaware,” said Oussama Jarrousse, a Syrian researcher and cyber-security expert, adding that this is an ongoing and unprecedented issue that should sound alarm bells.

“There are new videos from the same protest being taken down,” Jarrousse added, saying that videos removed in the past were mainly on the grounds of graphic and violent content.

“This is the first time we’ve seen such a case in the Syrian context.”

A representative of Facebook told MEE he would “follow up on the concerns raised”.

A new era of Syrian censorship?

Protests are a sensitive subject in Syria.

Anti-government demonstrations in 2011 were violently cracked down on by authorities, sparking the country’s ongoing war. Activists who organised protests and journalists that covered them were routinely arrested, tortured and killed.

Since then, public dissent has been a rarity.

Last month’s protests in Sweida, a majority-Druze city that has managed to tread a fine line between relative independence and acquiescence to Damascus, felt for many like a watershed moment.

Though Syria’s government has militarily all but won its war, it is struggling. The already wheezing economy is in freefall, buffeted by new US sanctions, coronavirus and an economic crisis in next-door Lebanon - and the effects are being felt in Syrians’ pockets.

Now the Syrian government is looking for ways to placate, or at least distract, its increasingly impoverished population.

“The Assad regime always smeared the protests in Sunni-majority areas as radical violence but in Sweida it can't [do the same],” said Suhail al-Ghazi, a nonresident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy think-tank.

“The regime is trying to push the narrative by saying the situation is stable but difficult and the citizens must adjust to it.”

However, Ghazi said, this state narrative that everyone has to play their part in bearing with a situation imposed on them by Washington may prove to be futile in quelling civil unrest.

In the meantime, Jarrousse fears a new era of censorship may be underway for Syrians.

“Copyright claims seem to be a new way to clamp down on freedom of expression and to suppress the dissemination of spreading videos of opposition or dissent,” he said with concern.

“The problem is ongoing.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].