Could the Gulf become a proxy in the new US-China cold war?

Rising US-China tensions are having far-reaching ramifications across the international order, stirring up problems not only for western powers, but also for smaller states falling into regions of influence. This includes the Gulf countries, which are increasingly squeezed between the competitive pressure of these great powers.

The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Bahrain and the UAE have historically been rooted in the US sphere of influence. But they are forging an increasingly close set of relations with China, carefully leveraging their geostrategic locations, financial powers and hydrocarbon resources.

By carefully playing one superpower against the other, they are prospering as “in-between” states - at least for now.

Shifting power dynamics

Since the end of World War II, the US has promoted a liberal international order based on the free-market rule of law. This has benefited advanced capitalist economies, especially the US. But the influence of this liberal order, and with it the US grip on international power dynamics, is beginning to wane.

China has offered an alternative to western free-market orthodoxy, learning to efficiently adapt its state-led capitalism to the global economy, effectively challenging US primacy in highly strategic industries by massively investing in technology and innovation.

For GCC members, this could go either way. They could continue to reap the security benefits of a continued US presence in the region, while enjoying China's economic cooperation

There is increasing concern in Washington that if the US loses its position as the world leader in technology, its global hegemony will wane. This situation is compounded by President Donald Trump’s isolationism and confrontational stance towards China, and the growing Chinese military power projection within the Western Pacific.

Yet, both powers are loath to openly confront each other militarily, despite the odd clash, as their economies are highly interdependent, with China deeply enmeshed in global supply chains. So far, this has led to a new type of cold war, where the two competitors clash in proxy arenas such as trade wars, Covid-19, Hong Kong, etc.

But like the original Cold War, there are other, less-widely reported manifestations of this proxy conflict in other regions of the world.

Growing influence

The rise of China in the Gulf comes as US influence is waning. Given the significant US military presence in the Gulf, it is not going anywhere just yet. US influence in the security domain will likely remain intact, thanks to decades of western-orientated military education and equipment purchases. Western financial hubs will also remain a key locus for Gulf investments.

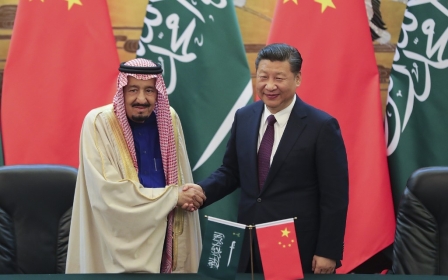

Yet, China’s influence is growing inexorably across the Gulf monarchies, on an increasingly sure footing. The Gulf is dependent on China to buy a significant portion of its hydrocarbon exports, just as China’s industry depends on these imports. Building on this point of commonality, Chinese investment across the monarchies increases.

The Gulf is an important hub in the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, something that boosts competition among Gulf nations as they bid for Chinese investments. Gulf investments have been diversifying in recent years eastwards, away from their traditional haunts of western capital markets and property investments.

In the security sphere, China plays important niche roles. International regulations prevent western nations from selling equipment such as drones (though the US is trying to relax these restrictions) so Saudi Arabia and the UAE acquire them from China, deploying them in conflicts, such as those in Yemen and Libya.

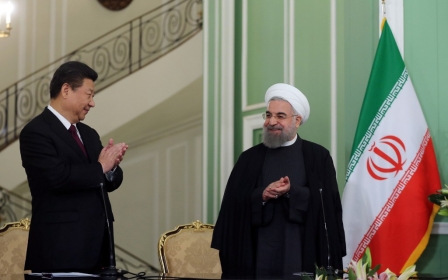

While this kind of arms trade is likely to increase, any prospect of China’s military playing a wider role in the region is broadly considered unlikely. Chinese forces lack the scale to involve themselves in the region in a significant way, and Chinese doctrine suggests a reluctance to get drawn into regional difficulties - not least because China will resolutely not take sides on regional tussles, including between the GCC states and Iran, another important hydrocarbon supplier to China.

Challenges and opportunities

Being stuck between two colossi can lead to hard choices. Yet, the current historical transition, with its geopolitical fluctuations, offers both challenges and opportunities. At this stage, the position of GCC members appears more favourable than that of other states.

Economic and political power in the Gulf are not as neatly separated as they are in Europe. This helps to mitigate tensions of the sort that have fuelled divisions within the EU. And while Europe represents an invaluable geostrategic asset that allows the US the luxury of a low-maintenance partner for offshore balancing, the Gulf has always needed US protection.

Gulf states are costly allies, making it difficult for the US to retain more than a necessary security presence while continuing to provide armaments.

GCC members are also less inhibited from forging closer links with China on the grounds of its human rights record and its actions in Hong Kong. The Gulf states even signed a UN letter endorsing China's record in Xinjiang, rejecting claims that it is persecuting its Uighur Muslim population. Still, the Gulf monarchies may be affected by increasing tensions in the South China Sea, given its potential to affect the international flow of oil.

While the conflict between the US and China has some similarities with the Cold War, the global distribution of power is no longer bipolar, as it was during the original Cold War. Rather, we are in a post-US order that is evolving in an uncertain, fragmented direction.

For GCC members, this could go either way. They could continue to reap the security benefits of a continued US presence in the region, while enjoying China’s economic cooperation. But if US-China tensions continue to mount around the world, the Gulf could be drawn in as a proxy in this new cold war.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Ths article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].