Iran: How a Marxist guerilla band sparked a struggle in Siahkal

As the sun set behind the high peaks of the Alborz mountain range, nine young Marxist guerrilla fighters, armed with light machine guns and grenades, descended from the snow-blanketed heights of northern Iran.

On 8 February 1971, the young men had one goal: to free one of their companions in arms, Hadi Bandehkhoda Langroudi, an engineering student who had been expelled from university for his activism against the Shah, arrested earlier that day and held in a gendarmerie post in the small town of Siahkal.

The nine young men stormed into the post, killing two officers, but they were too late. Langroudi had already been transferred to Lahijan, a bigger city about 20 kilometres southeast.

Their group was too small to attack the gendarmerie centre there, and the young fighters knew that once news came out of their attack in Siahkal, it was only a matter of time before all other military posts in the area went on high alert.

With a wounded member of the guerilla - a school teacher named Houshang Nayerri - in tow, the group clambered onto a Ford minibus they had commandeered on their way to Siahkal. But the old engine would not start.

Bystanders helped push the vehicle until it roared to life, taking the nine young men on a dirt road back to the mountains.

When the engine died a second time, the group abandoned the vehicle, disappearing in the winter's desolate forest. By 17 March, barely over a month later, all had been killed or executed by the Shah’s forces.

A failed operation by a small band of leftist idealists could have been an anecdote lost to history. But 50 years later, the Siahkal incident, as it became known, remains a symbol of uncompromising resistance against dictatorship in Iran.

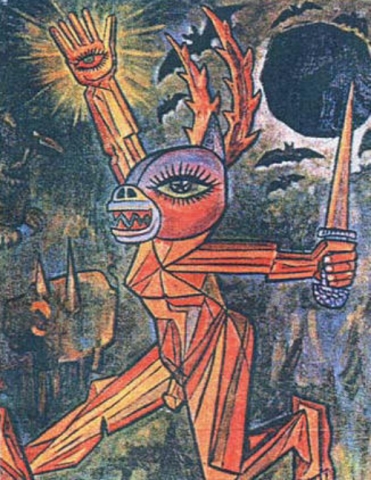

The fate of these nine young men has inspired tens of songs, works of art and movies, in defiance of unwritten bans both under the Shah and the Islamic republic following the 1979 revolution - as a potent symbol for countless Iranians who over the decades sought to stand up against government oppression.

Inspiring a new energy

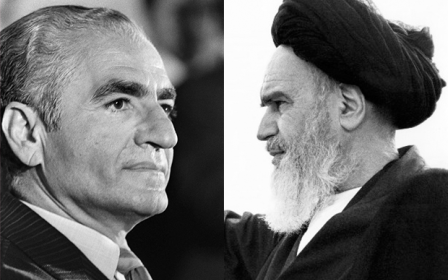

At the time of the attack, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had been ruling over Iran since 1941, brutally silencing all opposing voices since a 1953 US-backed coup overthrew democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mosaddegh.

Oil income cascading into Iran helped the Shah build the most powerful army in the Middle East with the support of the West and establish the Savak, the region's most infamous secret police with the help of the CIA.

"The 1953 coup and events following the Shah’s land reform programme in the 1960s created a degree of pessimism and an atmosphere of helplessness among those who opposed the Shah," explains Professor Maziar Behrooz, a historian at San Francisco State University.

"The Siahkal operation and the start of the [armed] movement managed to break through state censorship and create a sense of optimism among many people," adds Behrooz, whose book Rebels with a Cause: The Failure of the Left in Iran, analyses the 1970s armed movement in Iran.

Ali Ranjbar Yeganeh, a former political activist, was 18 years old when the Siahkal attack took place.

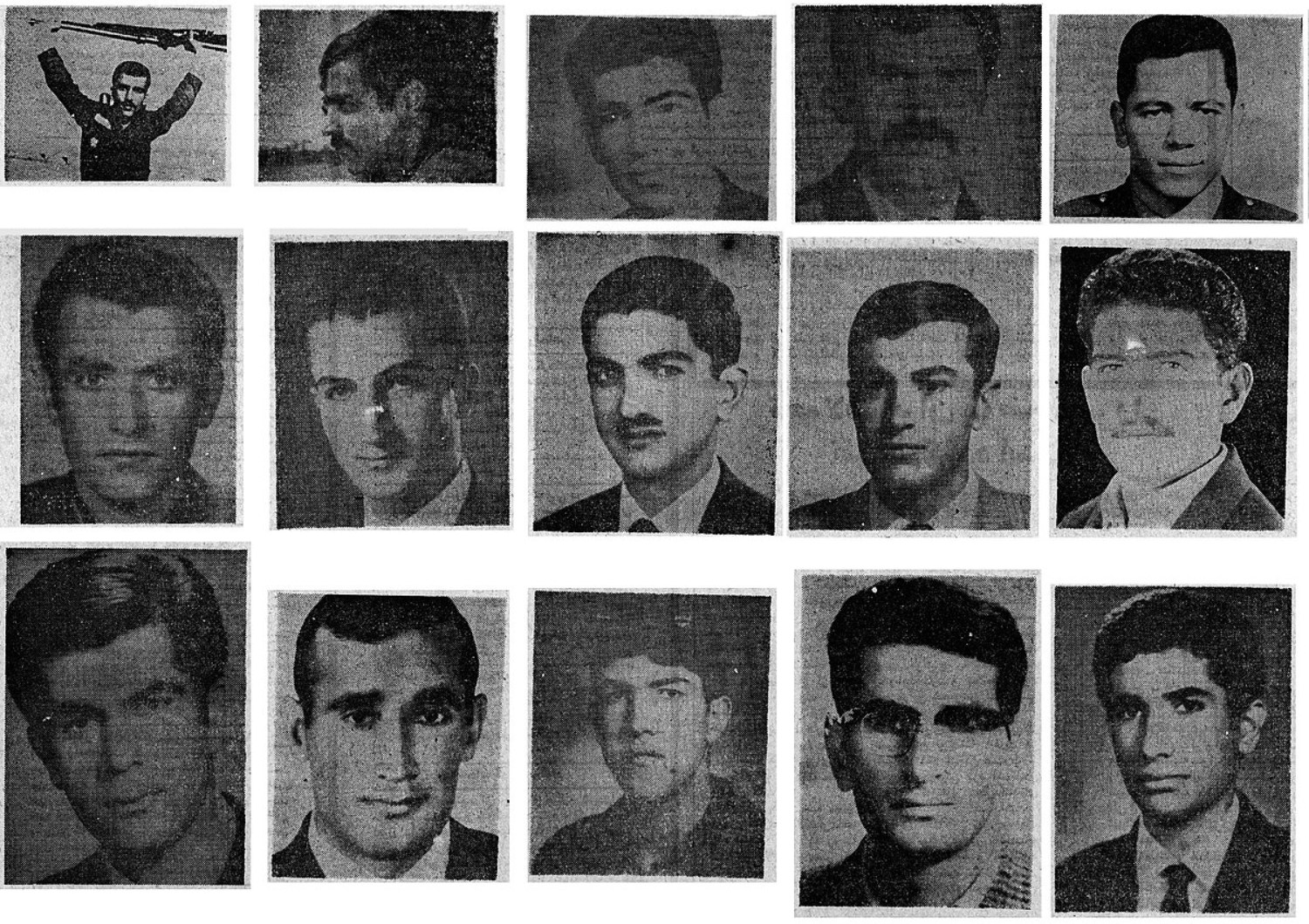

"When I saw the photos of the Siahkal group members, all wearing ties and clean-shaven, on the front page of the dailies, I was totally shocked,” he recalls. “I asked myself: how did those guys dare to do that?"

Inspired by events in Siahkal, Ranjbar Yeganeh joined a Marxist student cell in the city of Isfahan in 1973. He was sentenced to prison for his activism before and after the 1979 revolution.

"They didn't just inspire leftists. They pumped a new energy into all political factions who were fighting the regime,” he tells Middle East Eye.

“Before the Siahkal armed uprising, 'Yes, your majesty!' was the only answer to the Shah - but they showed it was possible to stand up to the Shah and hit back.”

When 'being killed was no problem'

After the Siahkal incident, armed opposition groups sprouted in Iran. Surviving associates of the nine young men joined ranks of other Marxists, creating the Organisation of Iranian People's Fedai Guerrillas (OIPFG).

Meanwhile, a group of religious university students who were blending a new ideology based on a mixture of Islam and Marxism also chose armed struggle as their strategy against the Shah, establishing the People's Mujahedin Organisation. Smaller armed cells such as Setareh Sorkh, meaning the Red Star, also took up arms at the same time.

‘Before the Siahkal armed uprising, 'Yes, your majesty!' was the only answer to the Shah - but they showed it was possible to stand up’

- Ali Ranjbar Yeganeh, former political activist

"Siahkal, as a revolutionary act, was the best kind of propaganda of the deed," Abbas*, an original member of the OIPFG whose brother was among the fighters of Siahkal, tells MEE.

"We were not fighting to win political power. We wanted to break the vicious circle of dictatorship and fear, and when I look back, I think we were successful," he adds.

"The Shah was killing our members, but youth in universities were looking to join our organisation. The Shah put us in prison, but he could not silence us even there, and had to exile us to prisons in remote southern cities. The Savak could not arrest the Fedais without sustaining casualties. This was enough for a suppressed society to create plenty of myths about us."

Abbas was himself arrested in September 1971 following an armed clash with the Savak, and sentenced to life in prison - only to be released in 1979.

In Iran between Two Revolutions, historian Ervand Abrahamian estimated that between the Siahkal operation and mid-1978, hundreds of fighters died - 177 killed in armed encounters, 98 executed, 42 tortured to death, 15 gone missing after their arrest, while seven committed suicide to avoid being arrested.

With so many casualties, the guerrillas earned profound respect in a society where martyrdom and heroic death have historically been valued.

Bahram Ghobadi was a member of the OIPFG medical team. In the summer of 1971, he was injured and arrested in a skirmish. "Being killed was no problem for the guerrillas," he wrote in 2004, in unpublished memoirs seen by MEE. "Our problem was to be arrested alive and reveal information about our comrades under the Savak’s brutal torture techniques."

Sentenced to death in a military court, Ghobadi was pardoned on appeal and sentenced to life in prison, only to be released from prison when the Shah was toppled in 1979 during the revolution that saw the current Islamic system come to power.

Enduring legacy

With the fall of the Shah in 1979, the guerrilla fighters who had been operating clandestinely for nearly a decade were now publicly hailed as heroes. On the 1980 anniversary of the Siahkal operation, thousands of leftist activists went to the northern town, chanting "We will turn all Iran into Siahkal."

However, the spring of political activism was short-lived for leftists, as the Islamic regime crushed them even harder than the Shah.

By 1981, the arrest and execution of the leftists was widespread. In 1988, Tehran carried out a mass execution of more than 4,500 leftist political prisoners. What the Shah had sought to tamp down in the 1970s, the Islamic republic succeeded in eradicating.

While Behrooz saw the OIFPG as successful in shaking the pillars of the Shah's dictatorial regime, the historian wrote that the Marxist fighters failed to bring it down, nor were they able to expand their influence beyond the circle of intellectuals.

"Although many sacrifices had been made, many military operations had been undertaken, and the organisation had established itself as a military-political force in Iranian society, it was unable to establish any kind of base among the working class ... it remained basically a militant guerrilla group, whose members were mostly from the intelligentsia," Behrooz wrote in Rebels with a Cause.

"One notable failure was that the [Fedai movement] was unable to take control of the [1979] revolution, and armed struggle did not become a mass movement."

For all its flaws, the memory of the Siahkal operation is still alive in Iran despite the government’s heavy-handed crackdown, as younger generations of activists born after the 1979 revolution continue to praise what happened in the Alborz mountains 50 years ago.

'The bravery of that generation, and the fact that they were willing to forfeit a comfortable life and put their lives on line, is another attraction'

- Professor Maziar Behrooz

"This rebellion was quite romantic, and romanticism is always attractive," Behrooz tells MEE. "The bravery of that generation, and the fact that they were willing to forfeit a comfortable life and put their lives on line, is another attraction. [That] this generation was willing to put its money where its mouth was, and follow up its political protest with concrete action was certainly another attraction."

The latter factor mentioned by Behrooz found importance again in the late 1990s when reformist Islamists' attempt to open up Iran's political atmosphere was thwarted by hardliners. After the brutal repression of Iran's 1999 student movement, whispers of reviving the Siahkal group's method of struggle were heard in certain circles of student activists.

However, that idea never gained more ground than fodder for heated discussions inside left-leaning student circles.

"You might laugh if I tell you that after the 1999 crackdown, with my closest activist friends, we talked about the possibility and necessity of the armed struggle," says Hamid Reza Akhtar, a former student activist who was sentenced to two years in prison in 2001 and now lives in exile in Canada.

"The Siahkal Group was a pioneer, and only if you are engaged in serious political activism do you understand how difficult it is to act as a pioneer, how difficult it is to start a new way," he tells MEE.

While the Covid-19 pandemic has limited Iranians’ ability to travel freely inside the country, the small town of Siahkal remains a discreet site of pilgrimage for leftist sympathisers seeking to visit the birthplace of modern armed struggle in Iran.

"I think their impact might not be clearly visible nowadays, but it exists in deeper layers of our society,” Akhtar says.

“Look at the fifty years of propaganda done by the two dictatorial regimes in Iran to defame the members of the Siahkal Group as terrorists or infidels. Even talking or writing about them was banned in Iran, but they are still alive for many Iranians."

*Name has been changed.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].