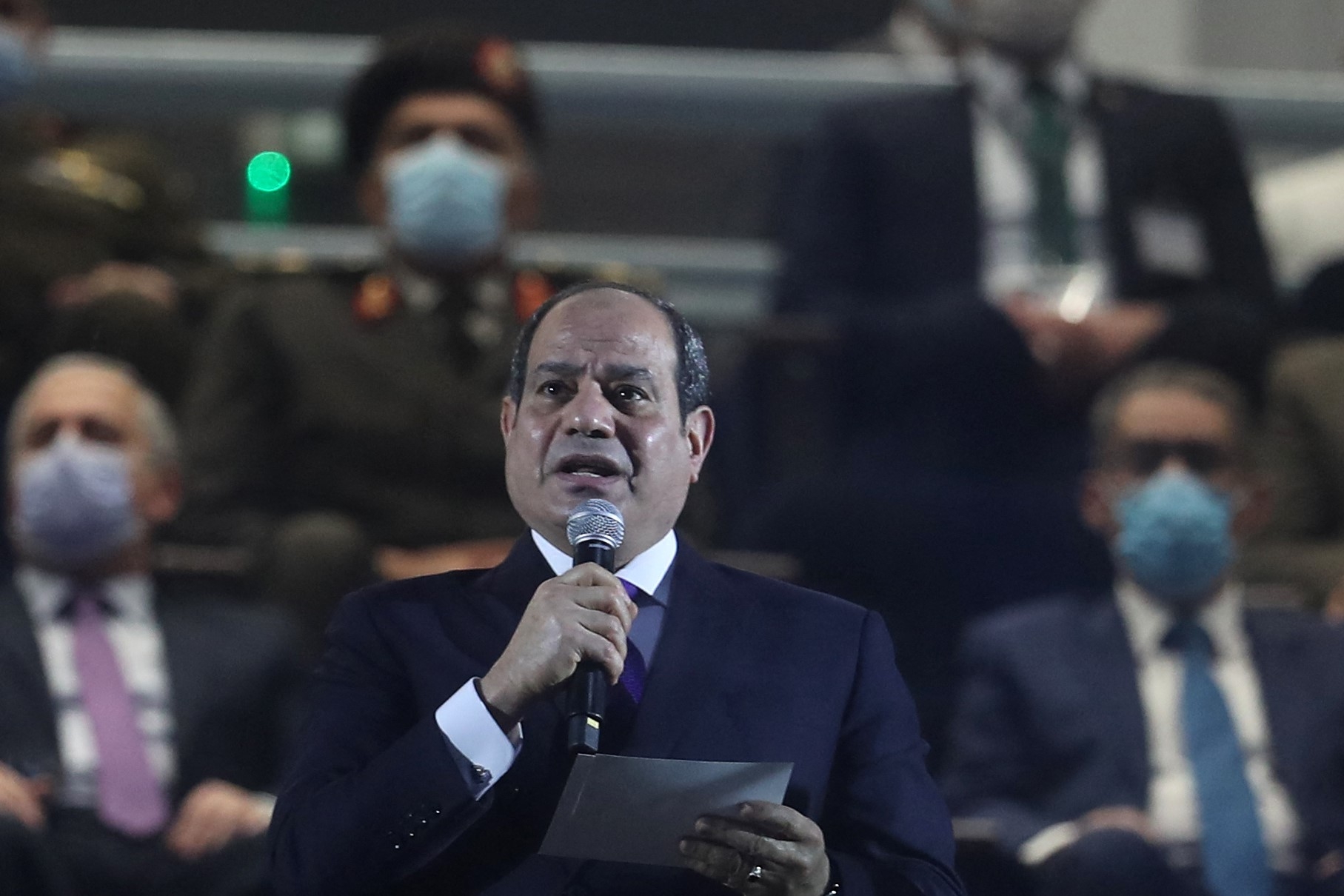

Sisi's debt fuelled policies could drive Egypt off a cliff

In March 2015, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi told an international investment conference that Egypt needed $200-300bn to “develop”. At the time, it seemed to be extreme hyperbole, considering that the size of the Egyptian economy in 2015 was $332bn.

Fast forward to November 2019, when Sisi boasted that the state had invested $200bn in projects over the past five years - a remarkable feat. But he neglected to mention that the regime followed a policy of debt-driven growth and heavy investment in mega-infrastructure projects with dubious economic benefits, laying the foundations for a profound economic crisis that is yet to unfold.

The roots of the crisis lie in a new form of militarised state capitalism that depends on the appropriation of public funds for the enrichment of military elites

The roots of the crisis lie in the regime’s political economy, which has spawned a new form of militarised state capitalism that depends on the appropriation of public funds for the enrichment of military elites, along with predatory austerity, rather than focusing on developing a durable competitive advantage anchored in a dynamic and innovative private sector.

This has led to not only a disappointing private sector performance, but also rising levels of poverty, lower levels of GDP growth, and weakened local market demand. This is combined with a weak tax base and shrinking government revenues, meaning that the only way for military state capital to accumulate is through additional credit.

This opens up the path towards a profound debt crisis, which is bound to occur in the case of an international economic slowdown. The subsequent credit crunch could lead to debt default, currency collapse and hyperinflation - the prerequisites for a mass social disturbance.

Last November, the World Bank issued a report predicting that Egypt’s public debt to GDP ratio would reach 96 percent by the end of the fiscal year 2020/21, up from a projected 90 percent the previous month. This is an increase from 87 percent in 2013 when the military took power.

During the same period, the level of external debt skyrocketed from 16 percent of GDP in 2013 to 39 percent in 2019, reaching a historic high of $123.5bn last June.

Last May, Egypt issued $5bn in foreign bonds, the largest issuance in the country’s history, followed by another bond issuance worth $3.75bn this month. This rapid rise in the level of debt has caused significant strain on the state budget; in 2020/21, one-third of expenditures were earmarked to cover loan and interest repayments, amounting to 556bn Egyptian pounds ($35bn).

Budgetary pressures

This pressure on the budget is compounded by decreasing government revenues and a weak tax base, as well as an under-performing private sector, which places additional pressure on government finances. Borrowing is the only feasible option not only to cover the government deficit, but also to continue the regime’s massive investment drive.

Government revenue as a percentage of GDP has dropped from 22 percent in 2013 to 19 percent in 2020. This is already low by regional standards, where neighbouring countries, such as Morocco and Tunisia, reached 27.5 percent and 25 percent respectively.

At the same time, Egypt’s weak, regressive taxation system is replete with exemptions for large corporations, both military and civilian, which benefits elite enrichment. It also weakens tax revenues, which according to the finance ministry reached 14 percent of GDP in 2020, lower than the African average of 16.5 percent in 2018 (with neighbouring Morocco and Tunisia reaching 28 percent and 32 percent that year).

Aggravating the problem is the weak performance of the Egyptian economy in terms of GDP growth, as well as private sector performance. GDP growth from 2015-19 averaged 4.8 percent, still lower than the average of the last five years of former President Hosni Mubarak’s long reign, although higher than the turbulent first half of the 2010s.

In terms of non-oil private sector performance, as of January 2020, it had only grown for six out of the past 54 months. This abysmal performance can be partially attributed to a drop in local consumption, which reflects weaker local demand amid rising poverty, which was not balanced by increased export performance.

Between 2015 and 2018, the total level of consumption dropped by 9.7 percent, while the level of exports as a percentage of GDP slightly increased, from 17 percent to 17.5 percent. In 2019, non-oil exports accounted for 48 percent of total exports, showing the weakness of Egypt’s competitive position. And the rate of economic growth is expected to slow further, reaching 3.5 percent in 2020 and a projected 2.3 percent in 2021 amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

Sisi's mega-projects

Hence, the source of Egypt’s economic growth lies in the massive influx of capital for infrastructure and construction. In 2019, the year with the highest growth rate since Sisi came to power, the largest contributor was the construction sector, which grew by an estimated 8.9 percent, fuelled by Sisi’s mega-projects.

The returns from most of these projects is dubious at best. For example, the Suez Canal expansion, which cost $8bn to complete in 2015, increased the canal’s revenues by only 4.7 percent over a five-year period, reaching $27bn during that period - a far cry from the $100bn annual return touted by the regime at the beginning of the project.

With a weak private sector, a regressive taxation system and the regime’s insistence on large infrastructure projects financed by debt, the seeds of a financial collapse have been sown.

The regime has no choice but to continue to roll over its debt and attempt to reduce government spending through increased austerity measures that are bound to increase poverty, drive up inflation and weaken local demand. This, in turn, will push the regime to borrow more to meet its financing needs.

This cycle is compounded by investment projects with low returns that serve only to enrich military elites. If sources of credit dry up, which is possible amid changes in the global economy, then Egypt would face possible state bankruptcy. The accompanying social disturbances, hyperinflation and currency devaluation would be of a historic scale - and the human costs would be immense for Egypt and the region.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].