Iran start-ups battle brain drain and US sanctions

Online start-ups have mushroomed in Iran in the past decade with entrepreneurs offering services as diverse as online shopping, food delivery, e-ticketing for movies and laundry services, among others.

As of the beginning of March, there are around 10,000 start-ups operating in Iran, according to the country’s Vice-President for Science and Technology Sorena Sattari.

While US and Western sanctions against Iran have deprived the start-up scene of international investment, they have also created opportunities for locals to capitalise on the absence of bigger US-based multinationals.

In a 2016 paper for the Atlantic Council, the former US under secretary of state for economic growth, Robert Hormats, said: “Years of sanctions have forced Iranians to create their own internet companies and services - and provided an incentive to establish a wide variety of homegrown information technology firms.”

With tech giants like Amazon, eBay, and Uber unable to offer services to a lucrative market of over 80 million consumers, Iranian companies have moved to fill their niches - often closely following the business models of their Western counterparts.

Renewed sanctions

However, tried and tested ideas alone are not enough to guarantee the success of such businesses. The restoration of sanctions after the US pullout from the Iran nuclear deal has left Tehran with a shortage of the political and economic stability that is a requisite for the success of any start-up.

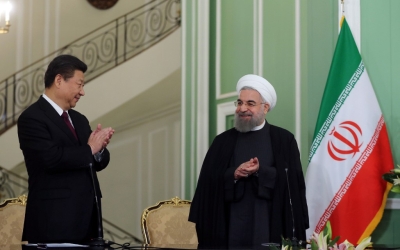

Up until then, sanctions relief under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) as it was officially known, had provided Iranian businessmen and entrepreneurs with a glimmer of hope. Under the deal, Iran and Western powers, most notably the US, agreed to lift some sanctions in exchange for curbs on Iran’s nuclear programme.

International investors took tentative steps to invest in Iranian companies, but with former US President Donald Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the agreement in May 2018, many Iranians' hopes for a deluge of foreign capital and investment were dashed.

“The months after the re-imposition of US sanctions caused our company to suffer,” says Mohammad-Reza Kheyrdush, the home sales manager of Sheypoor, an online classified marketplace.

After the easing of sanctions against Iran under the auspices of the Obama administration, companies like Sheypoor were able to draw in significant foreign investment. In its case, the Sweden-based Pomegranate Investment took a 43-percent stake in the company, but the foreign investors were forced to withdraw from Iran after the resumption of US sanctions.

According to Kheyrdush, it took a few months for Sheypoor to recover and “rise from the ashes” but others have not been so lucky. His former employer, the online real estate platform Aloonak, failed to secure a strong enough customer base after the reimposition of the sanctions. The difficulty was due to consumer uncertainty brought on by the Trump administration's decision. In September 2018 - two months before the sanctions came into effect - it was acquired by Sheypoor.

Trump’s unilateral withdrawal from the JCPOA had left the Iranian start-up ecosystem in tatters.

“The stakes rose unreasonably even for the most daring investors, who were willing to take risks for long-term yields in Iran,” says Reza Ghiabi, an Iranian business developer. “Political tensions grew out of proportion in the eyes of investors.”

Operating woes

The withdrawal of international investors brought with it an outflow of foreign currency, which in turn led to a drastic devaluation of the Iranian rial, further adding to the headache for Iranian businesses.

In 2015, when the JCPOA was signed, the rial traded at about 35,000 against the US dollar. However, the latest rates on the unofficial market indicate that over the past six years, Iran’s currency has experienced a 700-percent loss in value against the greenback, at almost a quarter of a millian rials to the dollar.

According to Mohammad-Reza Azali, the co-founder and CEO of TechRasa, a leading Iranian tech news platform, this devaluation has led to unprecedented inflation, tripling the price of hardware and software services needed for start-ups.

Where money is not an issue, finding foreign companies willing to do business with their Iranian counterparts is.

“As a result of sanctions, Iranian startups have been deprived of hosting, marketing and cloud services, and have been banned from certain software apps including Slack and Coursera,” said Azali, adding that the difficulties also extend to buying hardware.

Brain drain

The Iranian entrepreneurs Middle East Eye spoke to also complained that while there were possible workarounds to acquire equipment and software, sellers abroad were reluctant to engage for fear of potential complications.

As a result, entrepreneurs like Amir-Hossein Madadi find it near impossible to operate their businesses to their full potential. His start-up, Shenoto, is a podcast and audiobook platform with more than 100,000 users on the Android operating system but he finds it difficult to do business with those outside Iran.

“It might be possible in other industries to somehow bypass the sanctions, but it is not at all possible in this field,” he says.

This sense of impasse among businesspeople is in stark contrast to the mood when Iranian President Hassan Rouhani was first elected. While the Iran nuclear deal gave hope to many Iranians that their country was opening up to the world, its subsequent setback after the US withdrawal has left many wondering if they would be better off joining the Iranian diaspora abroad.

Iran has been suffering from a so-called "brain-drain" for decades before the Trump administration came to power. Since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the annual flow of migrants from Iran has averaged at about 63,000 people.

The total number of Iranian migrants abroad (including non-permanent residents) increased from about 830,000 in 1979 to 3.1 million today, according to a Stanford study. Their numbers include both opponents of the Islamic Republic and economic migrants seeking better opportunities abroad. As a result, Iranian businesses find themselves in a no-win situation where they both struggle to find competent employees and risk losing the ones they already have.

Vahid Rajabloo, the founder and CEO of Tavanito, the first Iranian start-up for disabled citizens, says employees grow by working at start-up companies, and once their skills are developed, they leave Iran for another country where their interests are better served.

“Start-up companies train and help elites to grow, but then that helps them leave the country more easily,” he says, adding: “If they decide to grow on their own, they would have a longer path to go. But when they are trained in major start-up companies, that helps them and even opens up their way to immigrate.”

For Rajabloo, those looking to leave need to ground themselves in a greater sense of patriotism towards their country. He describes the choice of whether to stay or leave as “a matter of conscience”.

“It's totally against humanity that a person chooses to work abroad just because their interests are better served in other countries,” he says. “That's forgetting their entire past and origins.”

Madadi takes a more forgiving approach: “What forces the elites to emigrate is a lack of hope for a better life and future. That’s not what high-tech companies (here) can give these people.”

Sheypoor’s Kheyrdush highlights another form of brain-drain, in which an employee need not leave Iran.

With the global rise of remote-working after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, many Iranians can work for foreign multinationals without ever leaving. While the foreign salaries would no doubt help the Iranian economy, Iranian companies are left with an even smaller pool of talent to recruit from.

“Many of the best programmers departed from Sheypoor,” says Kheydrush. “The same issue happened at other start-ups...The best ones are now working remotely with other countries, instead of helping (Iran’s) start-ups.”

Future hopes

There is near unanimity among the Iranian entrepreneurs who spoke to Middle East Eye that their prospects are tied to the future of the Iran nuclear deal. While the sanctions are ostensibly targeted at the Iranian government, the Iranian people have been significantly impacted.

While access to foreign markets has largely been closed off, Iranian businesses increasingly look at internal markets for solutions, thereby encouraging the growth of monopolies and reducing competition.

“The monopoly has stripped Iranian start-up companies of their right to choose,” Rajabloo says.

In response to the sanctions, Iranian officials are also developing internal networks and alternative platforms to ones available internationally that will make the country even more detached from the global internet. Such projects have the effect of increasing government control over what happens online.

“The high level of tension between Iran and the West has increased the likelihood of internet restrictions,” says Iranian business developer Reza Ghiabi. He further says that an internet shutdown, like the one in November 2019 which came in response to the nationwide fuel protests, is a “grave operational and financial threat to Iranian start-ups”.

According to the entrepreneurs, the way of addressing this threat is for all sides to return to the deal.

“A deal [between Iran and world powers] is needed to calm the situation, and that will lead to economic stability,” says TechRasa’s Azali.

“As long as Iran is fighting the world, there will be no economic stability, and that’s very important to entrepreneurs.”

The sentiment is shared by Sheypoor’s Kheyrdush who believes the lifting of sanctions will “attract foreign investment, increase competition, and finally benefit the end-user”.

However, there might not be a lot of time left for the Biden administration to secure a deal with the Rouhani government, which is considered moderate on the issue of the nuclear deal and has a track-record of engagement with the US. A more conservative candidate is expected to win the presidential election slated for 18 June.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].