'A life without war': Iran's booming art scene comes to London

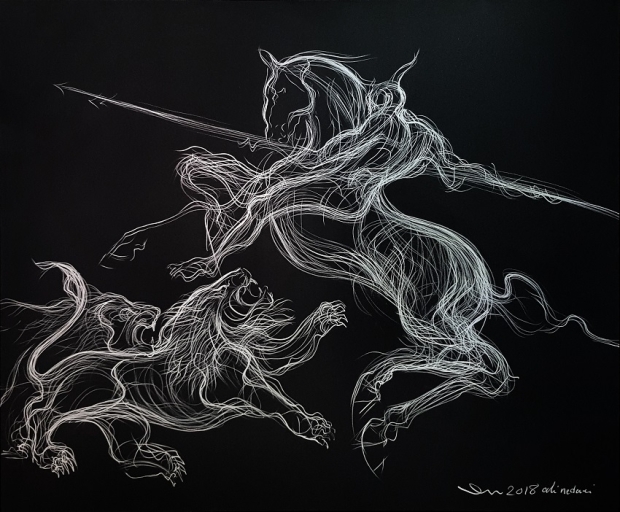

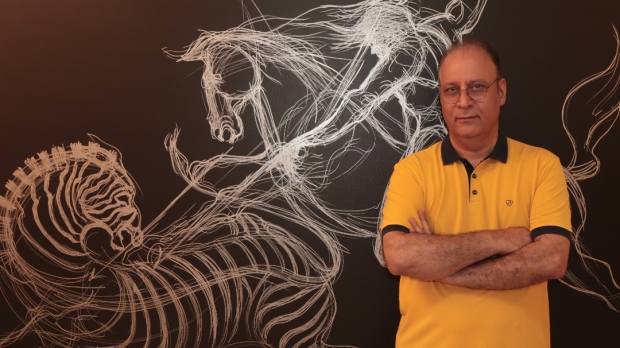

LONDON - Iranian artist Ali Nedaei’s exhibit at the Contemporary and Modern Art (CAMA) gallery in London is titled Silent Myths, but the 23 pieces on display there come across as anything but quiet.

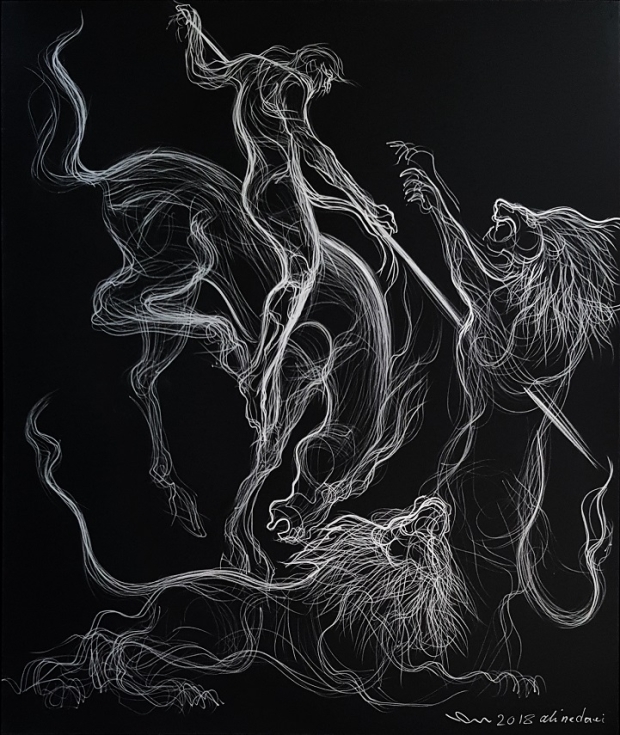

Silent Myths, which runs until 2 September, draws on Persian mythology, bringing to life his preoccupation with vast and abstract themes including war and peace, and good and evil. The running motif of the painter, who himself has experienced war, is a firm rejection of violence.

“I’d like the rest of the world to know that most Iranians are always seeking peace and tranquillity, and dream of a life without war on the planet,” Nedaei said in an interview with Middle East Eye via email.

“As a human being who has experienced war, my message to society is peace and friendship,” he added, referring to the Iran-Iraq war, one of the longest and bloodiest conflicts of the 20th century, which Nedaei lived through. The eight-year war left over one million people dead.

I’d like the rest of the world to know that most Iranians are always seeking peace and tranquillity, and dream of a life without war on the planet

- Ali Nedaei, artist

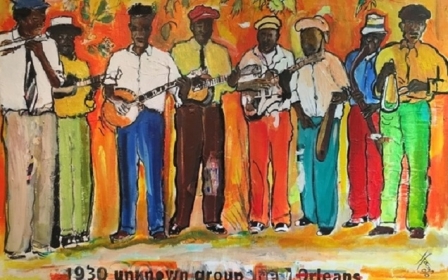

The men – painted in red, white and blue and connected by a single yellow rope – appear to be bound up or wounded from a battle they have only just emerged from. It is hard to ignore that the combined three colours evoke the flags of the US and UK. No one emerges from war unscathed, Nedaei appears to be telling us.

“If we look at human history from the past 2018 years, we see that it’s been full of wars, victories and failures. During prehistoric civilisations there may have been justifications for wars, but today, there is no excuse,” Nedaei said.

Silent Myths is Nadei’s first London exhibit. Due to UK visa restrictions, he wasn’t able to attend the London opening of the show. CAMA instead streamed a video of him speaking for the gallery's visitors.

While there are several London galleries that showcase Middle Eastern art, including Park Gallery and the Mosaic Rooms, CAMA is the only venue in the city whose focus is solely on Iran. The works that are presented at the venue, which opened in the UK capital in April, give visitors a rare look at Iran’s vibrant cultural life.

‘Peace for everyone’

Nedaei’s technique is precise and distinct, his single brushstrokes often so thin that up close, they resemble strands of horsehair. The resulting art is dreamlike: both man and beast appear to float atop the sprawling canvases they sit on, travelling from one dramatic piece to the next as their mythical stories build on one another.

In the poem, which literally means “Book of Kings,” Ferdowsi delves into the mythical reign of 50 Persian kings. Part one of Shahnameh focuses on the rule of Zahhak, an evil serpent king, who feasts on the brains of young Persians. He is killed by a blacksmith and succeeded by the valiant peasant Fereydoun. Nedaei’s painting depicts both men, aided by their respective beasts, about to charge at one another.

Stronger cultural exchange

Born in 1957, Nedaei has been immersing himself in art for almost 35 years. The painter experimented with larger-scale works for this particular exhibit, which was first shown in Tehran.

We want to take our artists outside the country, and to show that even after everything that's happened with the political situation, we can promote all kinds of positive aspects about Iran

- Ava Moradi, director of CAMA gallery

“We want to take our artists outside the country, and to show that even after everything that's happened with the political situation, we can promote all kinds of positive aspects about Iran, including art, art business, and art collaboration,” Ava Moradi, the gallery’s director, said in an interview at CAMA.

CAMA’s on-the-ground ties with the domestic art market in Tehran have allowed the gallery to respond to what it refers to on its website as “an increasing global demand for art from the Middle Eastern country”.

CAMA first opened in Iran in 2016; it has two venues in the country, and an office in Cyprus, in addition to its newly opened UK outpost.

The gallery, which was co-founded by Iranian siblings Mo and Mona Khosheghbal in 2016, has links with some 100 Iranian artists in the Islamic republic, 41 of whom work with CAMA exclusively.

Iranian artists must receive approval from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance before exhibiting their artwork in the country, and therefore need to take into account state-imposed rules.

Meanwhile, auctions in the city have been breaking record after record. That success has traversed borders: most paintings that were sold at Sotheby’s 20th Century Art / Middle East auction this year were by Iranian artists.

‘Politically neutral platform’

Nedaei’s paintings, which range from £5,000 to £30,000, are accessible to a wide investor base, according to Ryan Stevenson, a development consultant focusing on CAMA’s growth.

Art that is in the market is either of the pre-sanctions era, or has been smuggled out of Iran through various "proxies," he said. “As a result, it is usually incredibly expensive.”

Most people don’t understand the importance Iran holds in where we are as a civilisation

- Ryan Stevenson, development consultant

“The backing we have within Iran allows us to come in and bring the art out, whilst looking after the artists, and providing below-market value art,” Stevenson said.

Cultural exchange between Iran and the West has been strained by a protracted political crisis, despite a brief cooling period spurred by a 2015 international deal over Iran’s nuclear programme.

Following his election, Donald Trump backtracked on that detente, and on Tuesday Washington enforced sanctions on Iran that it had previously waived. Meanwhile, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani and Trump have recently traded barbs, one of which included a now-notorious all-caps tweet.

While the combined developments don't bode well for cross-cultural exchange, they haven’t fazed CAMA, which says it offers artists a politically neutral platform.

“Most people don’t understand the importance Iran holds in where we are as a civilisation,” Stevenson said. “There’s a forgotten part of the story, a missing link, and when we speak to people who are made aware of these things, all of a sudden, the narrative changes without us even attempting to change it.”

Beyond dynamic filmmaking

In line with its efforts to widen the scope of the West’s understanding of Iran, from August through October, CAMA will turn its attention to seven Iranian filmmakers. Time Lapse features a series of photographs celebrating the works of directors including Mohammad Rasoulof and the late Abbas Kiarostami. CAMA says it's stretched the exhibit “beyond dynamic filmmaking to the creation of fine art”.

The work of Jafar Panahi – who in 2010 was charged with propaganda against the Iranian government, banned for 20 years from directing films, and placed under house arrest – is on display at Time Lapse.

Panahi made headlines again the following year, when his documentary, This is Not a Film, was smuggled to Cannes by way of a cake containing a hidden USB stick. He is joined by a Qajar-era photographer, Mirza Ebrahim Khan Akkas Bashi, who is said to have popularised photography in Persia and who later would also become a filmmaker.

CAMA hopes the show will raise the profiles of the lesser-known film directors and photographers while honouring the greats.

“Now that the installation is coming to London, these artists will be more recognised outside of Iran,” Moradi, who herself is an Iranian artist with degrees in art business and literature, said. “ We’re bringing cultures together.”

*Ali Nedaei’s Silent Myths, which opened on 1 July, will run at the CAMA Gallery in London until 2 September. Time Lapse opened 2 August and will run through 2 October.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].