Turkey and the UAE: Making amends and talking business in post-Trump era

Late last month, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed held rare talks, in which they reportedly discussed bilateral relations and regional issues. According to the official Emirati news agency, Wam, the two leaders “reviewed the prospects of reinforcing the relations between the two nations in a way that serves their common interests and their two peoples”.

In a tweet, UAE presidential adviser Anwar Gargash described the phone call as “very positive and friendly”. Justifying his country’s acute U-turn, he noted that the call was based on “a new phase in which the UAE seeks to build bridges, maximise commonalities and work together with friends and brothers to guarantee decades of regional stability and prosperity for all”.

The UAE is working on promoting its 'new face' as a de-escalatory and constructive player, rather than a disruptive force

While the call surprised some observers, it should have been expected in light of bilateral developments between Ankara and Abu Dhabi over the previous few months. At the end of the Trump era, Abu Dhabi eased restrictions on the movement of Turkish businessmen and resumed daily flights. After the al-Ula agreement formally ended the Qatar blockade, Gargash made it clear that Abu Dhabi wanted to normalise relations with Turkey.

Ankara received the Emirati message positively, but demanded sincere, concrete and constructive steps. To show its seriousness and openness, Ankara appointed a new ambassador to Abu Dhabi. Soon afterwards, UAE Foreign Minister Abdullah bin Zayed spoke on the phone with his Turkish counterpart in April, expressing Ramadan greetings.

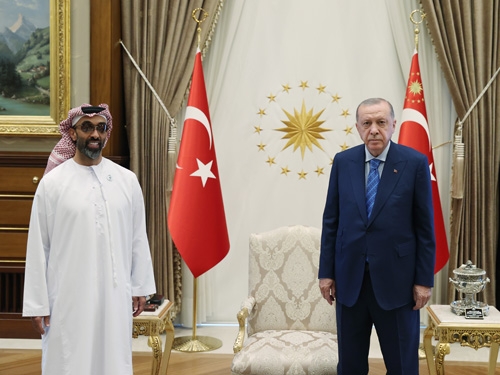

In August, just days before the phone call between the two countries’ leaders, the UAE’s national security adviser, Sheikh Tahnoun bin Zayed, made an unprecedented trip to Ankara to meet Erdogan. The Turkish president later said they discussed “serious investments” by the UAE in Turkey, leading some to question why, considering the sheikh’s portfolio, they would have discussed finances rather than security.

Finding common ground

There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, for Turkey, the intelligence channel has been the most effective in launching exploratory talks with other nations, such as Egypt and Israel, in hopes of finding common ground. In recent months, this channel has also been active with the UAE.

Secondly, the UAE is working on promoting its “new face” as a conciliatory and constructive player, rather than a disruptive force. It wants countries of concern, such as Turkey and Qatar, to take this message seriously, and sending its foreign minister to Ankara at this stage would not serve this goal. Abu Dhabi tried that approach with Ankara in 2016, and it didn’t end well.

Thirdly, Tahnoun is on the Supreme Council for Financial and Economic Affairs, established in 2020. He oversees a huge business empire in the Emirates, chairing several major companies, such as ADQ, the First Abu Dhabi Bank and Royal Group, among others. With this in mind, his perspective on economic relations is pertinent.

But the main question remains: why would the UAE mend fences with a country it has considered a sworn enemy, especially over the last few years?

As Abu Dhabi lost its bet on Trump, US President Joe Biden’s victory and the al-Ula agreement created new realities. As a result, Abu Dhabi’s allies, Saudi Arabia and Egypt, along with Turkey and Qatar, have been engaged in rapprochement efforts on several levels.

This past April, King Salman of Saudi Arabia invited Qatar’s emir to the kingdom. Weeks later, Saudi Arabia appointed an ambassador to Doha, which in turn appointed an ambassador to Riyadh in August. In line with these developments, Egypt’s foreign minister, Sameh Shoukry, said his country was burying the hatchet with Qatar. He visited Doha for the first time in years and even appeared on Al Jazeera.

Bilateral trade

Both Egypt and Saudi Arabia have also improved their relations to some extent with Qatar’s primary regional ally, Turkey. King Salman and Erdogan have spoken directly, while their foreign ministers have continued to discuss bilateral ties. At the same time, Egypt-Turkey relations have improved; in a first since Egypt’s 2013 military coup, a Turkish delegation conducted exploratory talks with Egyptian officials in Cairo in May - talks that are expected to continue in the weeks ahead.

These developments heighten the risk of regional isolation for the UAE, particularly amid a widening rift between Saudi Arabia and Abu Dhabi over various bilateral and regional issues. UAE-Egypt relations also seem cooler than they once were. While Abu Dhabi remains influential in Cairo, there are concerns over its relations with Ethiopia, among other issues.

Abu Dhabi is tasking Tahnoun with the mission and prioritising the economy, rather than ideology, as a means of finding common ground

As a client state and a disruptive regional force, the international and regional dynamics in the post-Trump era are not suitable for Abu Dhabi, significantly minimising its role. Paradoxically, Turkey and Qatar are rising in the region and beyond, with the most recent example playing out in Afghanistan.

To cut its losses, avoid isolation and secure a place for itself in the new regional game, Abu Dhabi is recalibrating its position vis-a-vis Turkey and Qatar and promoting itself as a constructive player. To give credibility to this message, Abu Dhabi is tasking Tahnoun with the mission and prioritising the economy, rather than ideology, as a means of finding common ground.

In the wake of the Qatar-Gulf crisis, the volume of bilateral trade between Turkey and UAE fell from around $15bn to around $7bn in 2018. One main reason was Ankara’s support for Doha. The current volume of trade stands at around $8.5bn, with around $2.7bn balance of trade in favour of Abu Dhabi. Clearly, there is room to boost economic relations to pre-Gulf-crisis levels.

In a post-Covid-19 period, the economic channel would be convenient for testing waters and mending fences. Turkey has a keen interest in boosting economic and investment relations with the Emiratis, but whether the UAE will go beyond that to fully normalise relations with Ankara and find a new regional role for itself remains to be seen.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].