Sultans of bling: How a rare set of Ottoman portraits reveal clues to a lost empire

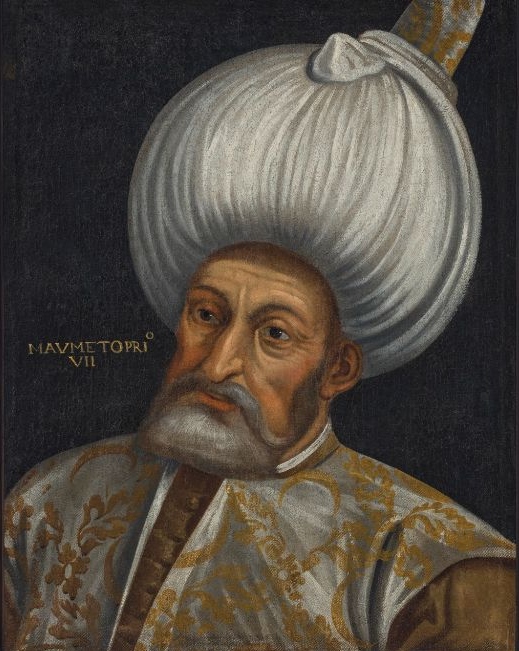

Each with his own style of facial hair, dark penetrating eyes and voluminous crown-like turban, the portraits currently awaiting the auctioneer’s gavel unmistakeably depict Ottoman royalty. The estimated price tag of a hefty £800,000-£1,200,000 further adds to their regal status.

Set to participate in The Art of the Islamic and Indian Worlds auction at Christie's, London, on 28 October, the six separate pieces depict Sultans Orhan I; Bayezid I; Mehmed I; Selim I and Selim II, as well as brother and rival of Mehmed I, Isa Celebi.

The portraits are believed to be part of a set, initially made up of 14 individual artworks, that were created in early 17th century Venice. Even more importantly, they are thought to be derived from originals commissioned by Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha. The commission allowed the Ottomans to document the all-important House of Osman.

“They are witness to the Grand Vizier’s efforts to create a dynastic portrait gallery. The result of which [an illuminated manuscript titled Şema’ilname by Seyyid Lokman] became canonical and represented one of the Ottomans’ most successful branding campaigns,” said Dr Julian Raby, a leading expert in Islamic art and retired director of Smithsonian’s Asian art galleries, who supported Christie's research and preparation of this set.

'This genre of works produced both by Ottomans and Europeans was steeped in diplomatic import with some pieces functioning as diplomatic currency'

- Dr Gizem Pilavci, research fellow at the British Institute at Ankara

A clue as to why the originals - and the set currently on sale at Christie’s - might have existed hides within a famous quote by a Venetian ambassador of the Ottoman court: “Being merchants, we cannot live without them.”

Despite a complicated and often fraught relationship that led to a series of wars between them, the Ottoman and Venetian Empires of the 15th to the 18th century relied on each other for trade. During peace time, they provided one another with access to crucial ports and exchanged essential goods such as wheat and soap.

Diplomacy at this time was therefore vital, and gifts were often used to maintain these good relations. These gifts could often be portraits.

“Beyond their role as visual documents of dynastic lineage, this genre of works produced both by Ottomans and Europeans was steeped in diplomatic import with some pieces functioning as diplomatic currency,” said Dr Gizem Pilavci, research fellow at the British Institute at Ankara.

But when the Grand Vizier to Selim II - Sokollu Mehmed Pasha - caught wind of some existing paintings of Ottoman Sultans in Venice and requested copies from the Venetian ambassador in 1578, Venice did not immediately grant the Ottomans their wish.

According to research conducted by Raby, Niccolo Barbarigo, the Venetian ambassador, denied knowledge of any existing paintings, stating only that there were some contrived prints that did not resemble reality.

These so-called contrived prints that Barbarigo referred to may have been those created in 1567 by Venetian printer Nicolo Nelli for the genealogical tree of the Ottomans - Sommario et Alboro delli Principi Othomani.

Whichever prints Barbarigo knew of, didn’t matter; Sokollu Mehmed Pasha was adamant that he wanted some portraits of the Ottoman sultans. He made his request again through a Jewish agent and this time he was successful - the Venetian senate commissioned a rushed set of portraits for the Grand Vizier.

By September 1579, the 14 original portraits were bound for Istanbul. Where they are now or whether they still exist is a mystery. However, it seems that multiple early copies of this original set of portraits were made; for example, one set of copies, complete with 14 portraits, resides in Wurzburg, Germany.

Fragments of two or three other sets were discovered in Topkapi palace, Istanbul, in 1924. The set currently awaiting sale at Christie’s is likely another.

“The existence of multiple 16th-century reproductions of the same series is significant in emphasising the centrality of Ottoman presence in the Mediterranean world of the period and the continual exchange between two sea-based empires,” said Dr Deniz Türker, assistant professor of Islamic art at Rutgers and affiliated lecturer at Cambridge.

“They also mark interesting, if lesser-known, moments of complex and successive artistic translations across cultures and media.”

Mysterious origins

Thanks to the persistent requests of the Grand Vizier, the original set was produced within just 10 months and it’s easy to imagine the flurry of the artist’s studio. It had initially been thought that they came from the hand of state artist and beneficiary of the Venetian ambassador Barbarigo’s family, Paolo Caliari - also known as Veronese.

However, with the whereabouts of the originals now unknown, this is questionable, none of the portraits in existence today bear Veronese’s very own personal mark, but rather that of his studio. This is due to the belief that these copies were the work of a "follower", possibly his son, under the guidance of Veronese. It was not an uncommon phenomenon for more than one copy to be produced at a time, and such a gargantuan task would have required many hands.

“When you look at the paintings, you can feel what they were like as actual ruling men. That’s something really special that people have always associated with Veronese,” says Behnaz Atighi Moghaddam, specialist at Christie’s.

“Yet, there is a painting by one of his sons which depicts the Safavid ambassadors being received by the Doge of Venice. That painting has a number of faces which are almost identical to the features of the sultans in our set. It’s very likely that there were sketches of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha’s original set at the studio where our set was painted.”

Hence, it is highly possible that the set on sale at Christie’s derives from the 1579 originals.

Raby’s research on the paintings has highlighted other attributes that suggest the Christie’s set were created in 16th century Venice. These include the format of the portraits and the material used. The three-quarter bust style is seemingly characteristic of Veronese’s studio and each has been painted on a twill canvas, the textile favoured by Venetian artists of the era.

The research also shows there are enough differences between the Christie’s set and those residing in Germany to indicate that each was produced individually, rather than the Christie’s set being later copies of the Wurzburg.

For example, the spelling of the names of two sultans varies; while the Wurzburg portrait spells Orhan as ‘Orcane’, the current set spells it as ‘Oracane’. Isa Celebi is also written as ‘ciriscelebi’ on the current set, as opposed to ‘iriscelebi’ on the Wurzburg one. Furthermore, the clothes worn by Bayezid I in the current set are different - they appear to be more brown wool than gold brocade.

'The set will likely generate important questions about factual and representational change across various artistic hands as they were continually reproduced'

- Dr Deniz Türker, assistant professor of Islamic art at Rutgers

For scholars of art history, the set on sale is significant. “If evaluated comparatively with other known copies, the set will likely generate important questions about factual and representational change across various artistic hands as they were continually reproduced,” said Türker. “It will also help us think through the trajectories of incomplete sets and highlight the broader network of patrons interested in owning and displaying portraits of Ottoman sultans.”

These particular portraits are being offered by a private seller and their provenance has been traced again to Germany - this time to Landshut, Bavaria. Before they were sold in 1935, the paintings were held by the Adelmann family.

“We know that the Adelmann family had a lot of contact with the Ottoman Empire,” says Atighi Moghaddam. “One of the most important histories of the Ottoman army was written by a member of the family,” he adds, referring to the book De Origine, Ordine, et Militari Disciplina Magni Turcae Domi Forisque Habita Libellus (The Origin, Order and Military Discipline of the great Turks At Home And Abroad).

It is also known that Christoph Martin Freiherr von Degenfeld, husband of Anna Maria von Adelmann, fought for the Venetians against the Ottomans in the mid-17th century, coming back a hero who was presented with many gifts. It may be that he later purchased these portraits as a reminder of his achievements. How they might then have come to remain in his wife’s family, however, currently remains undiscovered.

Turban renewal

The significance of the six portraits awaiting sale at Christie’s cannot be underestimated. It is the second largest series in existence after the Wurzburg set and the first time a set of Ottoman sultan portraits has come to auction. Other Italian-made portraits depicting Ottoman sultans have recently appeared in auctions, but these have always been singular works.

For example, in June 2020, Christie’s sold a single portrait of Sultan Mehmed II - otherwise known as Mehmed the Conqueror - with an unidentified young man for £935,250. It was one of only three surviving contemporary illustrations of Sultan Mehmed II. This piece was thought to have relied heavily on artist Gentile Bellini’s famous portrait of the Sultan, currently owned by the National Gallery in London, which was painted after the first Ottoman-Venetian war.

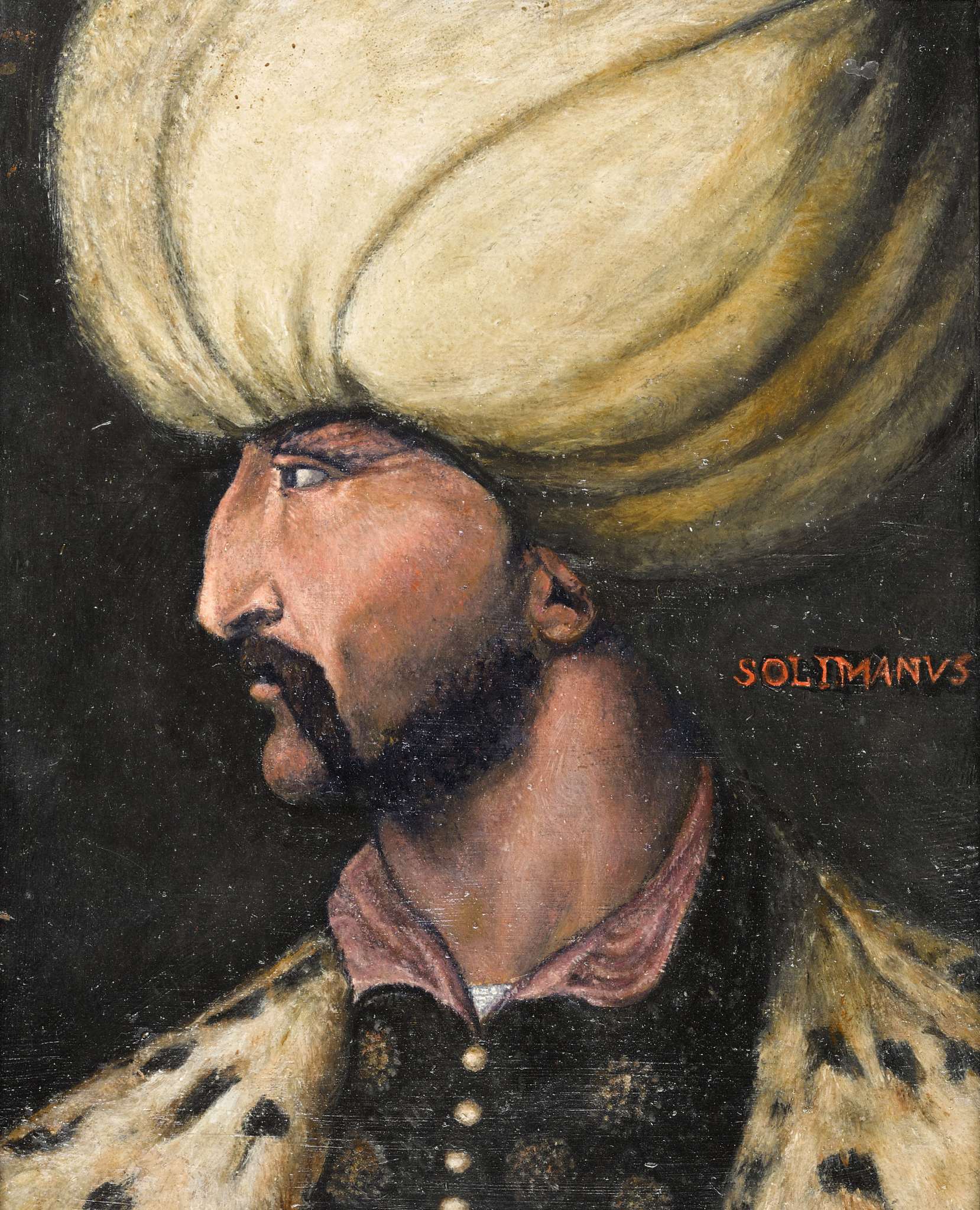

In March 2021, the auction house Sotheby’s sold a portrait of Sultan Suleiman at auction for £438,500. The work depicts Sultan Suleiman at the age of 43 and relates to two other known paintings of him at that age. Painted on copper, the piece is believed to have been created around the late 16th or early 17th centuries, similar to the set of portraits currently on sale at Christie’s.

However, neither were quite as special. “The quality of both of these portraits was dramatically different,” says Atighi Moghaddam. “The ones we are currently selling are on their original canvas and they’ve had such little restoration. They remain in remarkable condition, whereas the other examples did not.”

The size of the portrait sold by Sotheby’s in particular was also very different, raising questions as to whether it was ever part of a set.

“What makes this current lot so incredibly important and unique is the fact that six out of the fourteen paintings have survived. All the other sets we know of, aside from the Wurzburg set, are mostly fragmentary.”

Both the painting of Sultan Suleiman and of Sultan Mehmed II presently reside in Istanbul, having been gifted by an anonymous buyer and bought by the Istanbul City Council respectively. Whether Turkey will put in a bid to bring these current portraits home, however, remains to be seen.

According to Zeynep Boz, head of the department of anti-smuggling within the Turkish general directorate of cultural heritage and museums, the portraits aren’t on a watch list of any kind.

“These portraits have not been stolen from Turkey and I don’t know of an effort to get them back,” Boz said. “We already have our own collections of various portraits within the national palaces. As far as I know, there will be no attempt to buy them.”

Istanbul City Council, on the other hand, refused to comment for fear it would cause speculation.

Yet whether the portraits are ever repatriated or not, one thing is for certain: combined with the story of their provenance, they are a valuable piece in the jigsaw of Ottoman history.

Speaking of the 1579 originals, Atighi Moghaddam said: “This was such a big request to put to the Venetians. It depicted the ruling House of Osman. If the Venetians got it wrong, it could have really offended the Ottomans.”

Luckily, they didn’t.

Six portraits of Ottoman Sultans will be on auction at Christie's Auction House in London on 28 October

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].

!['[The portraits] are witness to the Grand Vizier’s efforts to create a dynastic portrait gallery,' says Islamic art expert Dr Julian Raby (Christie's Images 2021)](/sites/default/files/turkey-venice-sultans-potrait-auction-christies-3_0.jpg)