Shelf Life: The birth of the modern Egyptian bookstore

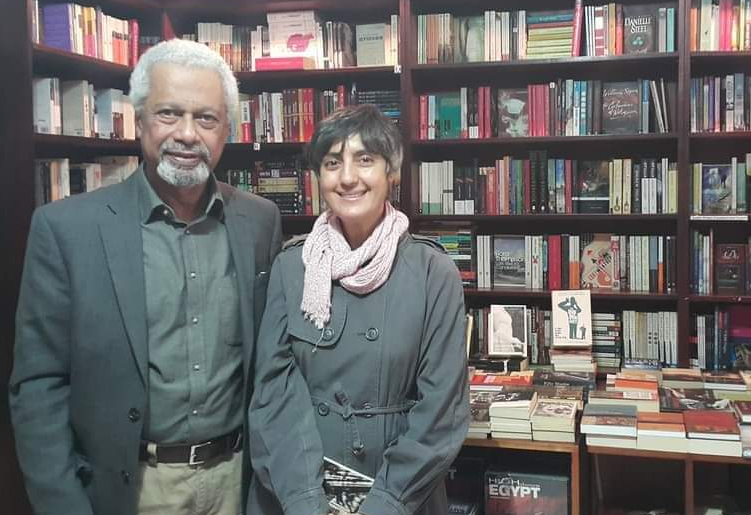

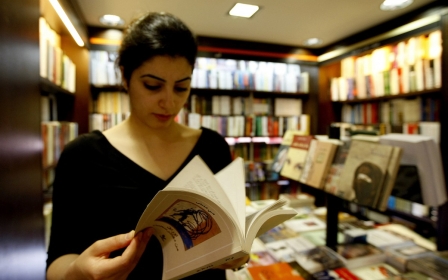

In the summer of 2002, three women decided to change Cairo’s bookselling landscape. They felt it was too inaccessible, too disorganised, and too male.

In Shelf Life: Chronicles of a Cairo Bookseller, out last month from Farrar, Straus & Giroux, one of those women, Nadia Wassef, explores the first 12 years of the journey of Diwan Bookstores, which opened shop on 26th of July Street in 2002 and has since spawned a chain of branches across Egypt.

A lot has changed in book publishing and distribution in the last two decades. Dozens of other bookstores have since opened up in the wake of that first Diwan Bookstore in Zamalek. Yet Cairo’s books sector still shows the deep imprint made by sisters Hind and Nadia Wassef and their friend Nihal Schawky.

The birth of Diwan

In Shelf Life, the story of Diwan unfolds in Nadia’s sarcastic, no-nonsense voice, which seizes the reader by the ear, leans in, and shares the intertwined stories of her life as “Mrs Diwan”.

In a weary aside that closes an early chapter, Nadia recalls how her partner Schawky was “relentless in her optimism”, in contrast to Nadia’s own natural cynicism. So much so that when a cafe regular tells Schawky about how she comes in daily, not because she’s a voracious reader, as Schawky cheerfully surmises, but for the carrot cake, Schawky still responds with an encouraging: “Good for you!”

It was July 2002 when Diwan opened its flagship bookstore in Zamalek, a shop conceived of one night over dinner in 2001. Nadia tells us that someone at the table asked, “If you could do anything, what would you do?” Both Nadia and her sister gave the same answer: “We would open a bookstore, the first of its kind in Cairo.”

Throughout the twentieth century, book-buying in Cairo had been geared largely toward a male clientele

As Nadia writes, bookshops everywhere are both private and public spaces. Throughout the 20th century, public book-buying in Cairo had been geared largely toward a male clientele. She describes the government-run bookshops she visited as a student as unwelcoming, and many publisher-run bookshops as smoky and male-dominated.

A different sort of Cairo coffee shop culture was also springing up around 2002, and Diwan became part of a movement to create new book-and-coffee-shop spaces with women in mind. Nadia writes that, when applying for a licence for Diwan, she explained to the government official that the business would sell books and have a cafe.

This bureaucrat told her that she would do no such thing: “A space can only be licensed for one activity. You can’t be a bank and a school. Pick one.” As in many other interactions, Nadia nodded and agreed, and then she did as she had wanted.

Yet it wasn’t just the cafe that made this space more welcoming for women. There were the clean, customer-friendly bathrooms, and there was also the bookstore’s investment in sections for “cookery” and “pregnancy and parenting”.

While those might not have been Nadia’s personal favourites, she was both a bibliophile and a gifted entrepreneur. She also cared about making a public space where women could browse books or drink coffee in peace, without being harassed.

The Classics

And while Nadia’s narrative begins with that store, she does not suggest Cairo was bereft of bookselling history. Every chapter is named for a section of that first Diwan bookshop, and, in the chapter The Classics, Nadia re-visits two classics of Cairo bookselling.

In this chapter, Nadia takes us on a road trip, first to a favourite stall in Soor al-Azbakeya, Cairo’s main book market, where books were available along the iron fence that enclosed Azbakeya Gardens, and then to Madbouly, a bookshop that opened in 1970 on Talaat Harb Square in downtown Cairo.

Nadia also gives us a glimpse of a Madbouly prequel, saying that her mother recalled seeing Hagg Madbouly on the beaches of Alexandria each summer in the 1960s, where, “Clutching a bundle of books held together by a leather strap, he’d shout, ‘Livres nouveaux!’”

Although not a bookshop, the annual Cairo International Book Fair was also an important part of book-buying throughout the latter half of the 20th century, a place where readers of most social classes could find books from across the region. Without this once-a-year intervention, Nadia writes, many books from around the region would have stayed “trapped under the rubble of failed distribution channels”.

A flowering of specialty bookshops

Diwan’s first location became not just a place to buy books, but a place to hold meetings, give lessons, meet friends, and attend cultural events. Five years later, Diwan opened its second shop in Heliopolis, in what became its most welcoming space. By then, others had come along to join in. Many of these shops were also owned and managed by women.

The Kotob Khan bookshop opened its first location in 2006. The bookshop, founded by Karam Youssef, started out in a prominent place on Laselky Street in New Maadi, and later shifted to a leafier location near the Cairo American College.

This bookshop, which also has a cafe, set out to be a haven for writers and serious literary readers. From the start, Youssef focused on bringing in major authors and put together serious creative-writing workshops.

The Kotob Khan publishing house launched in 2008, and its first book was a collection of work by creative-writing workshop participants. They have gone on to publish works shortlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (Adel Esmat’s The Commandments) and winners of the Sheikh Zayed Book Award (Iman Mersal’s In the Footsteps of Enayat al-Zayyat).

Another specialty bookshop is Balsam Books, which started as a publishing house. Balsam Saad started her children’s publishing house in 2004, and after that began working as an importer, bringing in children’s literature from other publishing houses. After several years, Saad wondered why she was hiding all these beautiful books in a warehouse.

In May 2010, she opened a child-focused bookshop in the affluent suburb of Mohandiseen. With the renaissance in Arabic children’s books that had begun a decade earlier, Saad was able to offer a wide range of high-quality children’s literature, in addition to readings and events aimed at young readers. Her store also became a place for international children’s book authors, illustrators and publishers to come for discussions of the art and business of Arabic children’s publishing.

A third fun specialty bookshop was also founded by women: Bikya Book Cafe, which opened up just before the seismic shifts of 2011, was launched by book-loving friends Rana El-Faramawy, Reem Khamis, Nancy El-Hady, Yara Taha, and Sara Boctor. The bookstore focused on used books and graphic novels, and it was a fun geeky getaway in Nasr City, which otherwise lacked independent bookstores. Unfortunately, Bikya announced they were moving in 2016 and did not re-open.

Others also looked to build on the Diwan model. The Alef Bookstore chain opened its first location in 2009, in Heliopolis, and spread rapidly, opening six more branches in just their first year. By 2015, they had 20 branches and were set to open a store in London.

Alef had a wide variety of books for readers of all ages, and their staff developed a reputation for being knowledgeable about books, but unfortunately, their bookstores have since all shut down, after the owner of their parent company was accused in 2017 of being part of the then-outlawed Muslim Brotherhood.

The bookstore chain, at that point the largest in Egypt, was taken over by the government and slowly closed down, with the last branch shutting its doors in December 2019.

Egyptian writer Ayman Howera summed it up on Facebook at the time: "10 years of success, including 8 years of brilliance … 37 branches and more than 250 employees and an inspiring success story for its team has come to an end.”

2011 and the surge in reading

Alef’s high tide had come after the 2011 protest movement that drove Hosni Mubarak from office, when there was a surge in creative activity across Egypt. In this period, Nadia Wassef writes in her memoir, Diwan’s customers “were reading more than ever”.

'The early revolution years produced infinite material for sarcasm, satire, and absurdism, all of which flourished in the newfound disorder and freedom from censorship'

- Nadia Wassef, Egyptian bookseller

While sales of their English books fell, Arabic book sales mushroomed. She adds: “The early revolution years produced infinite material for sarcasm, satire, and absurdism, all of which flourished in the newfound disorder and freedom from censorship.”

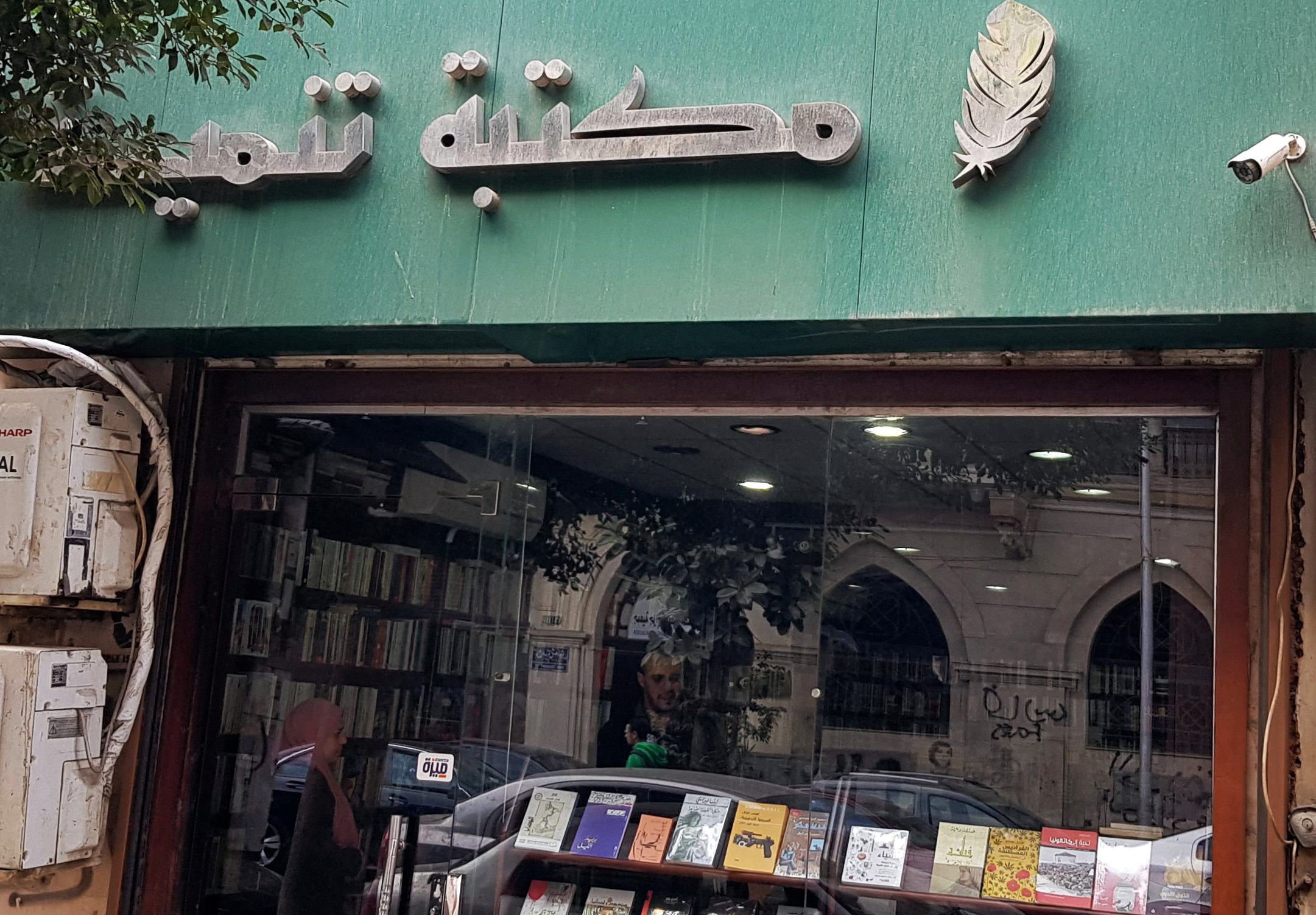

In 2011, many miniature library projects and bookshops sprung up. One that has persisted is Tanmia Bookstore, founded by long-time book distributor Khaled Lotfy, along with his brothers.

Like Kotob Khan, Tanmia also spawned a publishing house that has brought out a wide variety of award-winning works for children and adults, including popular translations of works by George Orwell and Stephen Hawking.

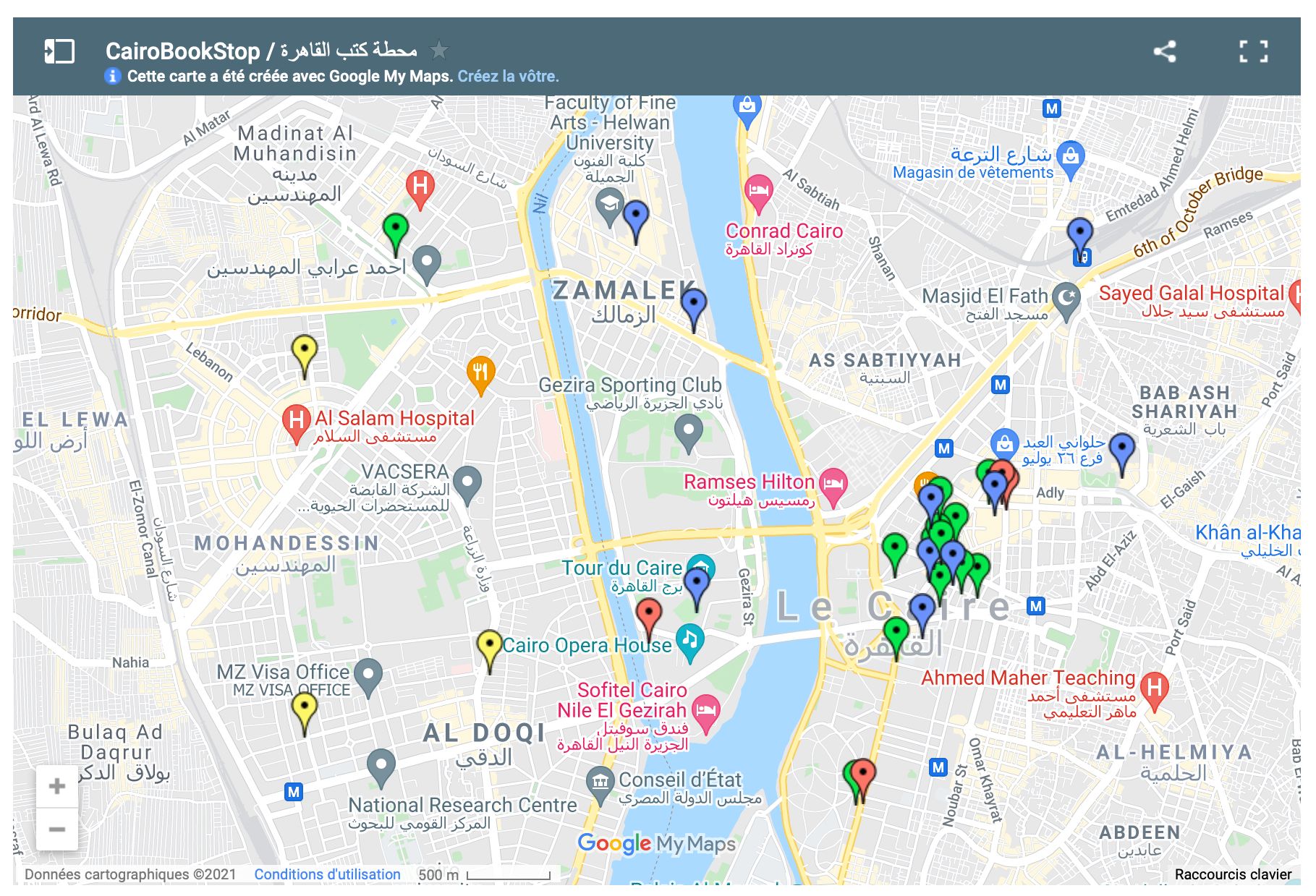

By 2014, there were enough book-buying options across the city that scholars Nancy Linthicum and Michele Henjum thought newcomers needed a map.

They launched their Cairo Bookstop project of mapping Cairo’s bookstores. Linthicum and Henjum added photos and notes about different bookstore locations, bookstore history, accessibility, and helpful notes about what you might find at each bookshop.

Although the website is now out of date, there is still a great deal of valuable information. Also, as a glance at the map shows, most bookshops are clustered in just a few areas: downtown, Zamalek, Maadi, Heliopolis, and Nasr City.

The map thus highlights the importance of projects like Gamal Eid’s now-closed Karama library project, which opened up essential library spaces in book-impoverished neighbourhoods.

It was around this same time in 2014, Nadia Wassef writes in Shelf Life, that Cairo’s bookstores began to run into difficult economic times. She tells us that “buying patterns shifted as collective fatigue set in, eventually giving way to disillusionment”. Although Wassef ends her memoir around 2014, there were yet harder times to come. Still, as she suggests, Diwan has continued to survive them.

New challenges, new solutions

After the pound was floated in November 2016, bookshops were hit hard by the rapid change in Egypt’s exchange rates.

And today, 19 years later since that first Diwan bookshop was launched, Egypt’s bookstores face a host of new challenges.

Amazon entered the Egyptian market in September 2021, 'with a focus on selling books with the lowest prices to dominate the market'

The current CEO of Diwan, Amal Mahmoud, says that the bookstore chain has been beset by a new series of challenges. Amazon entered the Egyptian market in September 2021, “with a focus on selling books with the lowest prices to dominate the market.

"On top of all the above, the growing popularity and preference of e-books compared with printed books has become a major challenge for bookstores in Egypt.”

And while Kotob Khan thrived for much of the last 15 years, the last several years have been exceptionally difficult, driving several bookshops out of business. Those that remain face “high costs of rent, electricity, salaries, difficulties in importing books, high prices, and customs fees,” Youssef said.

She added that there are also “multiple modes of book availability, whether on Amazon Kindle, Google Books, or even pirated.”

The Cairo books landscape faced another loss when, in 2018, Khaled Lotfy, founder of Tanmia Bookshop and Publishing, was arrested and brought up on military charges. Lotfy, who was accused of sharing state secrets by co-publishing an Arabic translation of Uri Bar-Joseph’s The Angel: The Egyptian Spy Who Saved Israel, was sentenced to five years in prison. This sent ripples of fear and outrage through Cairo’s literary community.

Tanmia Bookshop and Publishing persists as a landmark on Huda Shaarawi Street in downtown Cairo, and with a second location off the Ring Road in Maadi. During the pandemic, which has been particularly hard on Egyptian bookstores, Tanmia offered deep discounts, including a special discount for doctors.

Still, the store continues to thrive. At the end of October 2021, Tanmia hosted a packed event with bestselling Kuwaiti novelist Bothayna al-Essa, with fans of her books packed wall-to-wall.

Other bookstore spaces followed in Diwan’s footsteps, refusing to be “either a bookstore or a coffee shop,” but insisting on being multi-use spaces. The Sufi Bookstore in Zamalek, which opened in 2012, is a space for a cafe, arts, live music, film, yoga, and more.

In Garden City, the multi-purpose Falak Bookstore and Art Gallery continue to thrive, seven years since its opening.

Kotob Khan owner Karam Youssef suggests that, if Cairo’s bookshops want to survive, they will need to “change the shape and quality of the experience”. She suggests they will need to turn into workspaces or spaces that host workshops.

Yet bookshops such as the Diwan chain, Tanmia, Balsam, and Kotob Khan have, through all these challenges, managed to keep their doors open.

And if they are going to continue to stay open, Youssef adds, individuals will need to support their neighbourhood bookshops. The survival of bookshops, she says, isn’t just a matter of Egypt’s economic situation, but is “also linked to the individual’s awareness of the importance of the ongoing existence of bookshops”.

By the time Nadia Wassef’s Shelf Life ends, she has learned a lot about bookselling, Egypt, and relationships. Diwan’s ups and downs are mirrored by the ups and downs of Nadia’s personal life, especially by her relationships with her two husbands, who she amusingly depicts as Number One and Number Two.

Marriages begin and end, she tells us, just as bookshops open and close. Nadia's two marriages ended, and, in the same way, she left Diwan when it was the right thing for her to do, moving to London in 2014.

“After twenty years as Mrs Diwan, I hope I’ve managed to get divorced, which, as I learned, is not the same thing as failing,” she writes.

Now, when she visits Diwan, Nadia says she tries to keep her hands to herself, allowing Diwan’s shelves to belong to someone else.

Egyptian bookstores are facing another wave of change, but the Zamalek store remains.

“On March 8, 2022,” Nadia reminds us, “the Zamalek store turns twenty.” Then she adds insistently at the end, as if despite all else, “Egypt is blessed.”

Shelf Life, a memoir by Nadia Wassef, is available from Macmillan Publishers

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].