Turkey blamed Syria for a deadly air strike. Its troops blame Russia

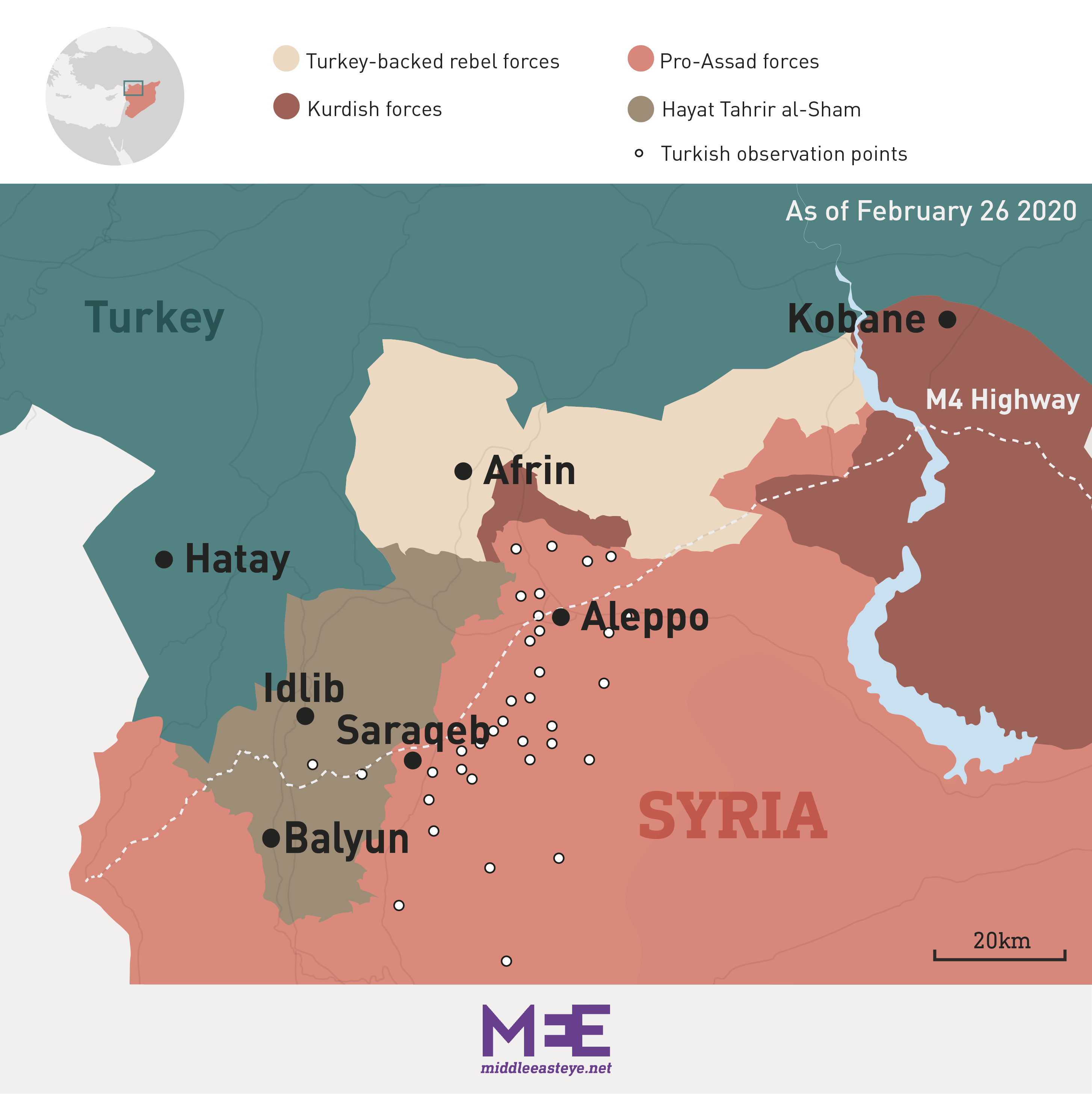

On 27 February, 2020, four missiles slammed into a convoy of Turkish soldiers near the village of Balyun in southern Idlib, the Syrian opposition’s last stronghold.

The group of at least 80 men, sent to reinforce Turkish-backed rebel groups, scrambled for cover in a local building.

The day before, anti-government forces had taken the strategic Idlib town of Saraqeb, but for months the Syrian opposition had been losing territory and soldiers to the Russian and Syrian air forces, fighting on the opposite side of Syria’s bloody civil war.

Captain A.H., currently working for the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army, was returning north from the front, alone on a motorcycle, when the bombs struck in the distance.

Heading towards the rising smoke, he came across a single wounded soldier sitting among olive trees by the roadside. Seeking help, he had managed to walk several kilometres from the scene of the attack.

“He had shrapnel wounds on his head and body,” A.H. told Middle East Eye, speaking anonymously, like the other current and former soldiers, officers and military officials interviewed for this story, for fear of dismissal or prosecution.

Roughly one hour after the attack, A.H. was the first to arrive at the scene.

“Martyrs were lying on the ground, corpses were everywhere,” he told MEE. Some were buried under rubble. “The scene that I saw was very bad... the wounded were at the roadside.”

Turkish military vehicles were “almost destroyed”, he said. “There were fires everywhere.”

When backup arrived they tried to help the wounded. Two cars were filled up with injured soldiers. Taking two other Turkish vehicles at the scene, they departed for the nearest medical point.

“I tried to reach the Turkish military but they initially dismissed our reports,” he said.

The convoy’s communication lines had dropped out before the attack, so they couldn’t radio it in for back-up. (They had been deployed without air cover, one military source told MEE). And with fierce fighting raging in other areas, the reaction back at Turkish headquarters was to reject reports of a hit. They would have known, they said, if a convoy had been struck.

But two hours later, as the evacuated wounded began arriving at the Turkish border, they realised what had happened, according to a Turkey-aligned Syrian National Army commander deployed nearby at the time. Still, it was another hour before anyone reached the wounded.

The Turkish government kept quiet for hours after the bombardment, even after Syrian and Turkish journalists had begun reporting on it.

Finally, that evening, nearly 12 hours after the bombs struck, Rahmi Dogan, governor of Hatay, a Turkish city close to Syria, stood before television cameras and described “an air strike by regime forces in Idlib", pointing the finger at the Syrian air force.

Turkish soldiers involved in the fighting in Balyun that day were furious. The author of the attack, they insisted, was not Syria, but Russia.

Astana silence

Turkey and Russia and Iran, which are both allied to the Assad government, have long maintained that diplomacy, in particular the Astana process - efforts to negotiate a de-escalation that began in 2017 - is the only way forward for Syria.

The country's bloody civil war has claimed more than 350,000 people, according to the UN, though the UK-based Syrian Observatory of Human Rights puts that figure at over half a million.

Ever since the agreement, Turkish ministers and high level officials have refrained from publicly criticising Russian action in Syria: even when air strikes have killed civilians or struck near Turkish observation stations.

Soldiers and officers speaking to MEE for this article expected outright condemnation after the 27 February 2020 strike, which killed 34 people and wounded more than 30.

It was the deadliest single day for Turkey since intervening in Syria in 2016, and the Turkish army's single biggest loss of life on foreign soil since the 1974 military operation of Northern Cyprus.

But while public officials in the days after the striked hinted at Russian involvement, the Turkish government has maintained that it was the Syrians.

The Russian defence ministry agreed, saying that Syrian pilots, confused by opposition forces in the area, hit Turkish soldiers by mistake.

Bunker-busters

Syrian and Russian jets were flying over Turkish targets on the day of the attack. They had been clustering above Baylun all day.

Twin take-offs and close flight formations were a familiar tactic from the allies: while one or two Russian warplanes took to the skies from the Hmeimim base, Syrian planes would take off from the southern bases of Homs or Hama.

"Regime and Russian warplanes fly side by side. In short, they shield each other to prevent the downing of their warplanes by Turkish forces," said a Turkish colonel.

'The Russians had targeted areas very close to our convoys on that day at least four times'

- Turkish soldier

“The Russians had targeted areas very close to our convoys on that day at least four times,” a Turkish soldier deployed near Balyun in one of several convoys told MEE, despite multiple warnings from Turkish officers to their Russian counterparts.

“There was an ongoing [Turkish] coordination with the Russians... They always knew where we were.”

Then, suddenly, bombs struck the areas ahead and behind the convoy, he told MEE. “The first direct hit struck the vehicles before some of our soldiers found cover.”

Often, the perpetrator of an air strike from a joint Syrian-Russian flight group can be deduced from the type of bomb dropped.

If the target is a specific point or a shelter, it likely came from the Russians: according to Turkish military sources, Syrian planes cannot drop so-called “bunker-busting” bombs, which penetrate hard targets such as walls before exploding. Syrian government planes are also unable to ensure a direct hit on a precise target.

Two Turkish military officers speaking to MEE who examined official photographs from the area said it was clear the hits were targeted.

One of the bombs used on 27 February was “obviously a penetrating bomb”, a senior Turkish military source directly involved with the incident told MEE.

“We reached the area that evening - multiple bombs had been dropped. Two buildings there before had been completely turned to rubble.”

'What will protect us against Russia'?

“Could this attack have been prevented", a Turkish special operations veteran asked. “Yes. Everyone says the S-400s [a Russian missile defence system] will protect us against the West. So, what will protect us against Russia, who killed 34 of our soldiers?”

“Russia gained psychological superiority with that. They already had military superiority,” a retired high-ranking officer told MEE.

Even more infuriating for Turkish military sources speaking to MEE was the Russian reaction to the strike. Ankara tried for hours to convince them to secure a safe passage to extract the dead and wounded, according to military officials, who say they refused.

“We couldn’t open an air corridor and we had to send medics by foot under sporadic bombardment,” a high-ranking officer running Syria operations said. “[The Russians] first told us that they thought they hit the Syrian opposition... Later they denied their involvement altogether.”

The Turkish government has never launched an investigation into the incident. Turkish and Russian jet radar records from the day have never been published, nor have the results of investigations carried out by the military experts at the scene.

The army’s only reaction was to dissolve the 65th mechanised infantry brigade, most of whose soldiers died in the attack. Survivors were assigned to other units.

Some within government-aligned circles say that Ankara did the right thing by blaming the Syrians: Turkey didn’t have enough firepower to take on Russia.

With nearly one million displaced Syrian civilians heading for Turkey’s border, and its Idlib observation stations surrounded by Assad’s forces, the government had been trying to push Moscow for a ceasefire for months.

And seven days after the strike - and Turkey’s intense retaliatory offensive against Syrian forces, pummeling 200 Syrian government targets and killing more than 300 Syria-aligned soldiers - Turkey and Russia reached such an agreement, turning Idlib into a "de-escalation zone".

The repercussions

But not holding Moscow responsible for the attack played into the hands of the pro-Russian clique within the Turkish military and government, according to several sources within the military. As well, of course, as Russia itself.

In recent months, the Russian and Syrian air forces have intensified their aerial assaults, pushing Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to seek another meeting with his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin.

The two countries have been negotiating to stage a Turkish military operation in the Syrian border town of Kobane to clear Syrian Kurdish YPG units there, Middle East Eye reported on Monday.

Officials speaking to Bloomberg last week said that Turkey was considering leaving some small parts of Idlib to the Russians in return for support for an operation in northern Syria.

For now, though, hostilities continue. Last weekend, Russian jets again hit the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army headquarters in the Afrin region, only a few kilometres from the Turkish border.

“We could have seized Damascus in 40 days if there wasn’t a Russian presence in Syria,” a Turkish colonel told MEE, reflecting on the years-long Turkish campaign.

“The Syrian army is total trash. We can hit the Syrian army as much as we want, but it won’t create a deterrent, because the Russians were the ones who struck us.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].