Turkish doctors increasingly seeking posts abroad as Covid and currency issues bite

"I was an assistant doctor. It was around 2am when a man, who refused to stay in the queue in the accident and emergency area, suddenly attacked the doctor just standing near me," recalls Sena Kerimoglu*, a public health specialist in one of Istanbul's biggest hospitals.

"'If you were a man, I would hit your head, too!' he shouted. I began screaming when I saw the doctor bleeding on the ground.

"Why should I continue doing this job without even my life being safe?"

Kerimoglu is just one of thousands of doctors who have left or are considering leaving the profession in Turkey for brighter opportunities in Europe and particularly in Germany.

A hard grind of 36 hours continuous work at least eight times a month, physical and psychological violence, low pay, and mandatory service in remote areas, now exacerbated by a global pandemic, have all helped stimulate the exodus.

The trend comes despite Turkey long priding itself on what it considered a successful health sector, claiming even to lure patients from Europe.

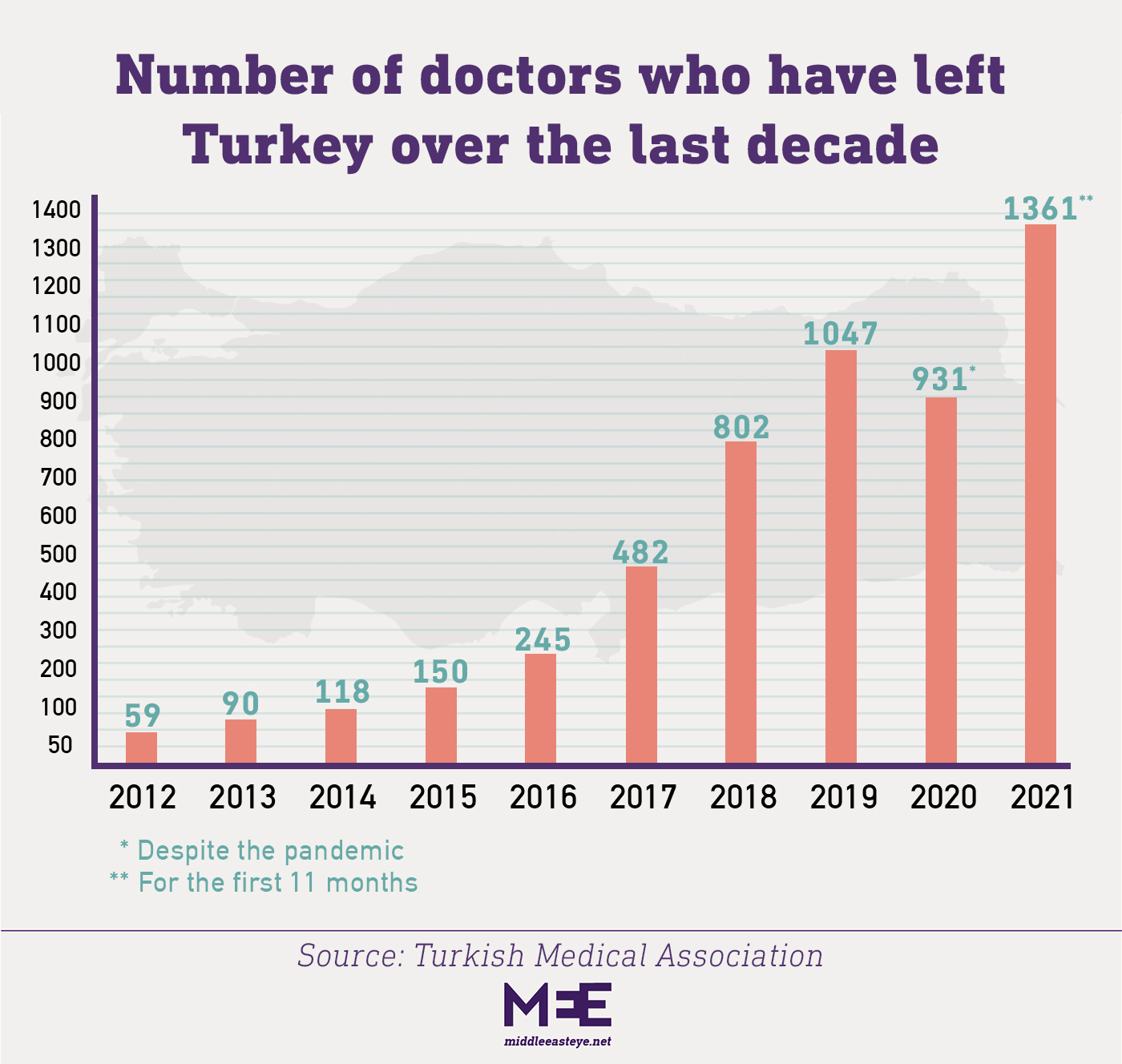

According to figures provided by the Turkish Medical Association (TMA), the number of doctors who left Turkey in the first 11 months of 2021 was 1,361. This compares with just 59 in 2012.

As seen in the chart below, the number has continued to increase every year in the intervening period.

The vast majority of those leaving Turkey are doctors who have recently graduated. Given that 15,000 people graduate from medical faculties each year, Turkey is currently losing almost 10 percent of its doctors to establishments abroad.

Sebnem Korur Fincanci, the head of the TMA, told MEE: "The number of doctors who want to go to abroad is increasing incrementally.

"I'm afraid no doctor will be left unless an effort is made to keep them in Turkey."

The TMA also reported that more than 8,000 state-employed doctors had resigned in the first year of the pandemic, before this option was suspended.

There are now groups on Telegram with thousands of members of health workers, including not only doctors but also nurses and other staff, who consult each other on how to where to apply for positions abroad and which documents are required, including how to obtain an equivalence certificate.

'Extraordinary situation'

For many doctors already disillusioned with their roles, the pandemic was the last straw.

"It was a disaster during the beginning of the pandemic," Elif Temiz, an assistant doctor at a state hospital in Rize, told MEE.

"I had to treat Covid-19 patients despite being a psychiatrist. I can accept that as it was an extraordinary situation. But the working conditions are awful and unhealthy. Also, the shifts were so long and frequent that we barely protected our health," said Temiz.

"That is why many of us contracted the coronavirus."

As of June 2021, 403 health workers had died of coronavirus, according to official figures released by the TMA.

However, the number is believed to be higher since each coronavirus-related death was not always properly reported.

'Swearing from my superiors'

The worsening economic conditions also incites disappointment among doctors.

"Currently, a specialist doctor earns around 12,000 liras [$1,050] a month," Ahmet Yucel, an assistant doctor at a state hospital in Istanbul, told MEE.

"Imagine that the average house rent in Istanbul is not less than 4,000 liras.

"Market prices keep increasing. Every day, we wake up with another rise on basic goods, whether it be milk, cheese, bread or oil.

"Furthermore, I work around 40 hours a week, excluding the night watches. Every day, I hear swearing from not only patients but also by my superiors," Yucel said.

"I can't explain the abuse that we [assistant doctors] face. Tell me one reason to stay here!

"I spent years to become a doctor. I was among the first 100 students in the university exam. The reward is abuse, violence and struggling to survive!" said Yucel, who is in his mid-20s.

'How long should I endure these conditions?'

Despite the pressures, medicine remains one of the top faculties in Turkish universities. It requires students to reach the top 0.5 percent in university exams, which are sat by some 2.5 million people.

For Turkey's top and oldest medical faculties, such as Istanbul University's Capa faculty, this percentile goes up to 0.01 percent.

After six years of study, students are assigned for mandatory service. Graduates then sit another exam, the TUS (medical expertise exam), to begin their education for specialisation in a particular field.

Following this, doctors are required to fulfil another period of mandatory service at a hospital designated by the state.

If they wish to continue their education in a sub-branch, they must go undertake a third mandatory service.

The fact that doctors are mostly sent to underdeveloped and remote areas, and that they have to fulfil three mandatory services, often harms both their social and family life, making it difficult to switch to a settled existence.

"So, after all these efforts, with no social life, how long should I endure these conditions?" asked Kerimoglu.

"I have to spend one-and-a-half days at the hospital almost 10 times in a month, constantly treating patients.

"This is neither sustainable nor healthy. Moreover, it is impossible to provide good treatment when a doctor must take care of hundreds of patients every day."

Demanding patients

According to the TMA, as of 2020 there were 164,594 doctors in Turkey, meaning the number of patients per doctor was 498, nearly 50 percent more than the 341 per doctor across the 30-member OECD as a whole. The OECD, or Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, includes Turkey as a member.

While doctors complain about the high volume of patients, the system is also at fault.

Many patients say they are unable to book an online appointment at a state hospital, so they arrive at accident and emergency in the hope of being sent to an already busy specialist.

Often, such people should in any case be applying to primary health clinics for their first treatment, rather than going to hospitals.

"The tiered health system, which aims to receive patient initially in a primary health clinic and only dispatch them to a state hospital when required, doesn't work in Turkey," Ahmet Kulfalli, an assistant doctor at a state hospital in Istanbul, told MEE.

"Indeed, a professor should not be so easily accessible. Imagine, we see patients every day, with very simple complaints, who demand to be treated by a renowned professor.

"They refuse to go to primary medical clinics. In Europe, it's not possible for a patient to book an appointment with a specialist until they have been put forward by a primary-care physician."

Acts of violence

Kulfalli, who is in his late 20s, also believes that neither the government nor hospital management backs doctors against acts of violence or baseless complaints.

Doctors, he said, are vulnerable to both patients and management.

"One day, it was around 5pm, the work shift was about to end, So, we were not taking any patients," he said.

"One man came and yelled at us, saying that we had to treat him. When we refused, he went directly to the chief doctor, saying that he was a relative of the mayor [of that district].

"Then, the chief doctor called me and yelled, ordering us to treat him immediately," Kulfalli said. "I can't imagine such a thing would happen in Germany."

In 2020, 11,942 cases of violence against doctors were reported, but TMA head Fincancı said unreported acts of violence were higher than this.

Unqualified hospital management

Gulseren Yenice, an assistant doctor in her early 30s in Istanbul, said only one intern doctor out of 150 in her hospital last year was studying for Turkey's medical expertise exam.

"I'm not exaggerating - 149 of the interns at my hospital were studying for exams in either the US or Germany," she said, noting that even she was learning German.

Yenice cited increasing violence, economic conditions, and the ascendancy of unqualified people to top positions in hospital management thanks to their political ties in Ankara as the main reasons for the exodus of doctors.

"Even professors are seeking ways to find a place for themselves in a German or Swiss hospital," she said.

"Why shouldn't they, when a doctor barely survives under these economic conditions, in addition to constant threats from patients, the hospital management, as well as abuse from unskilled but Ankara-provided privileged managers?"

Germany lures doctors

Despite the strong desire of many doctors to work abroad, it's not at all easy for them to become registered as a doctor in a European country

The bureaucratic procedure is very detailed and irksome, varying country by country and even state by state in some countries, such as Germany.

Umut Karapinar lives in Germany, offering advice on visa issues and other requirements through a Telegram group to doctors who would like to immigrate.

"The bureaucratic process takes a very long time, around 12 to 18 months," said Karapinar.

"Also, it costs more than 10,000 euros [$11,300], which is a considerable amount of money today, given the depreciation of the Turkish lira against foreign currencies.”

However, he said, Turkish doctors have a chance in Germany, since the country desperately needs more doctors, and, according to Karapinar, working conditions are far more favourable.

"In the last few years, thousands of doctors from Turkey have wanted to come to Germany or Switzerland due to overloaded working hours, continuous shifts, stress and economic conditions," he said.

Comparing conditions with Turkey, he said: "Here, in Germany, a doctor works around 40 hours a week, with the possibility of reducing this number to 20. So, they have a social life here."

Strike action

Germany has facilitated the immigration of skilled and qualified people from abroad in several sectors, including medicine.

In 2020, almost six percent of doctor positions in Germany remained unfilled.

Accelerated by the pandemic, Germany employed more than 56,000 foreign-trained doctors in 2020, compared with less than 20,000 before 2010.

Incentives for workers include the right to become a citizen at the end of five years, and in some special cases just three years. The normal qualification time is currently eight years.

In Turkey, some health workers went on a strike last week, demanding the government increase salaries and improve working conditions.

TMA head Fincanci said: "Our doctors are vulnerable against Covid-19, inflation and inhumane working conditions.

"Why should they stay here? Following strike action, the government hastily put forward regulations for better working conditions and salaries.

"But they failed to pass the bill due to their incompetence and internal disputes."

'I want to serve my people'

An official from the health ministry, speaking on condition of anonymity, told MEE the government was aware of the fact that so many doctors were emigrating.

"This is a serious problem, and the government is doing its best to prevent this migration," the official said. "We’ll do the required regulations as soon as possible."

In a speech to parliament earlier this month, Health Minister Fahrettin Koca also highlighted the issue, warning: "We shouldn't forget that the wealthiest countries eye our doctors."

Despite all the problems, some doctors have still spoken up for the profession in Turkey.

Hatice Rumeysa Bulucu, an intern and a graduate of Turkey's top medical faculty, Capa, told MEE: "This country supplied the opportunity to me to get an education at top schools, including the medical faculty, without paying anything.

"They even gave us the books. I am also aware of these problems, but I belong to this country and want to serve my people."

While Bulucu shared the concerns of her colleagues, acknowledging how doctors suffer from violence and a poor standard of life, she believes that things will improve.

* Note: The names and/or surnames of interviewees except Umut Karapınar and Sebnem Korur Fincanci were changed by the author at their request since they feared their words could put them in trouble as state employees.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].