Syria: Joining China's Belt and Road will not bring in billions for Assad

In January, Syria signed up to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), raising hopes that Beijing will provide its war-weary economy with much-needed investment.

The UN estimates that Bashar al-Assad’s Syria will need $400bn to rebuild after a decade of conflict - but he has struggled to find anywhere near that sum. Assad’s allies Russia and Iran lack the funds, western governments refuse to work with a dictator they accuse of war crimes ,and Gulf investors are wary given Syria’s continued instability. So, might China now finally be coming to Assad’s aid? It is unlikely.

This BRI invitation is primarily a political rather than an economic move and won’t initiate a wave of Chinese investment.

It helped that Chinese Islamists had travelled to rebel-held Syria to fight alongside anti-Assad forces, and Beijing was happy to support Damascus’s efforts to eliminate them

China’s current embrace of Assad is unsurprising. Throughout the civil war, it rejected western claims that the Syrian president had lost his legitimacy and joined Russia in vetoing multiple UN resolutions that threatened him. As well as insisting on Syria’s sovereignty - an argument China has repeatedly made elsewhere, partly to ensure that it too has a free hand with its own population - Beijing believed Assad was the best chance for stability.

It helped that Chinese Islamists had travelled to rebel-held Syria to fight alongside anti-Assad forces, and Beijing was happy to support Damascus’s efforts to eliminate them. Unlike Russia and Iran, China kept its distance from the fighting, but there was little question it was in Assad’s camp.

With Assad long stating his admiration for the "Chinese model" of economic development, it was logical that Damascus hoped to transform this nominal wartime backing into post-conflict investment. In September 2017, Damascus named China, alongside Russia and Iran, as "friendly governments" that would be given priority for reconstruction projects.

Cautious investor

Beijing did show some interest. Over 1,000 Chinese companies attended the First Trade Fair on Syrian Reconstruction Projects in Beijing, pledging $2bn worth of investment, while a further 200 attended the 2018 Damascus International Trade Fair. There has also been some limited investment in the Syrian automotive sector, while Beijing agreed to send $16bn worth of aid, including 150,000 Sinopharm Covid-19 vaccine doses.

However, China is a cautious investor and Syria is not an attractive proposition. Though Assad’s position in Damascus looks secure, he has not extended his control over the whole country and there remains the risk of renewed fighting as well as sporadic terror attacks.

There is a limited consumer market, given that most Syrians have been impoverished by the war and post-war hyperinflation, while the deep corruption of the Assad regime means a lot of investment will be skimmed off. In addition, the US’s Caesar sanctions, which punish any company that deals with Assad, are a deterrent.

Importantly, despite limited oil and gas deposits, Syria lacks the wealth of key raw materials that has seen China risk investing in unstable places elsewhere. Syria’s entry into the BRI has changed none of these deterrents and while the memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed sets out an intention for eventual investment, it will not produce the sudden injection of funds Assad badly needs.

So why has it been signed now? For China, there is a geostrategic logic. This public embrace of Assad sends a signal to three important actors.

Firstly, to the United States, which has upped its confrontation with China under President Joe Biden. Bringing Assad into the BRI highlights how ineffective the US and its allies have been at isolating post-war Damascus, underlining the sense of ebbing US global power.

Secondly, to Assad’s allies, Russia and Iran, who want Syria’s isolation broken. This is a relatively easy way for Beijing to earn goodwill from both, with Iran in particular already an important BRI partner.

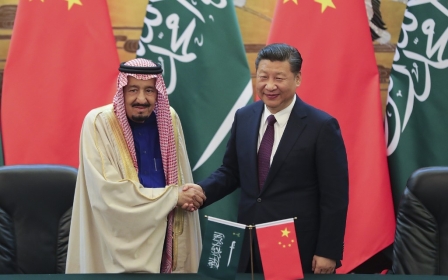

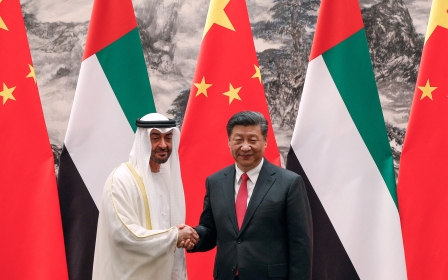

Finally, to other Middle Eastern powers, such as Israel and the Gulf states. Another Middle Eastern state entering the BRI indicates the deepening role of China and the need for regional powers to further their already considerable cooperation with Beijing - much to the chagrin of Biden.

The economic side of things is not insignificant for China, of course. Syria is strategically located with a sizeable Mediterranean coast and, should it ever stabilise sufficiently, could prove an attractive partner for China. But this is a potential long-term bonus for Beijing, rather than the immediate driver of the MOU.

Indirect economic benefits

And what of Assad? He is surely aware of the unlikelihood of significant Chinese reconstruction funds in the short term. But again, politics is an important driver. Joining the BRI serves a domestic agenda, holding out hope, however forlorn, of major Chinese investment for an impoverished population struggling in a crippled economy.

Damascus hopes alignment with China will encourage other non-western nations, and even some rebellious European ones, to re-engage with Syria

It also reinforces the ruling regime’s narrative that the rest of the non-western world is accepting Assad, strengthening his claims to legitimacy. Internationally, too, Damascus hopes that alignment with China will encourage other non-western nations, and even some rebellious European ones, to re-engage with Syria.

There may also be some indirect economic benefits. While China may not stump up the cash needed, its nominal presence in Syria signals to others that Damascus is one step closer to stabilising. This might prompt Gulf players to tentatively invest, reigniting pre-war networks to get in before Beijing.

While huge sums from Beijing are unlikely, joining the BRI might still facilitate a limited increase in Gulf investment and some funds from China. If it comes alongside further normalisation from Middle Eastern states, non-western Chinese allies and even some European states, it is clearly of benefit to Assad.

This may not mean his economy gets the hundreds of billions that it needs to recover, but it helps prop up the beleaguered dictatorship for a bit longer.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].