Egypt boom leaves poor high and dry - and Ukraine war will make things worse

Last November, the Egyptian government announced that GDP growth had reached 9.8 percent for the first quarter of the 2021/22 fiscal year - the highest quarterly growth rate in 20 years, signalling a robust post-pandemic recovery.

This was followed by an announcement in January that Egyptian non-oil exports achieved an all-time high for 2021, reaching $32bn, compared with $25bn the previous year.

The most notable factor is the regime's ongoing neoliberal dogma and insistence on eroding social supports for the most vulnerable

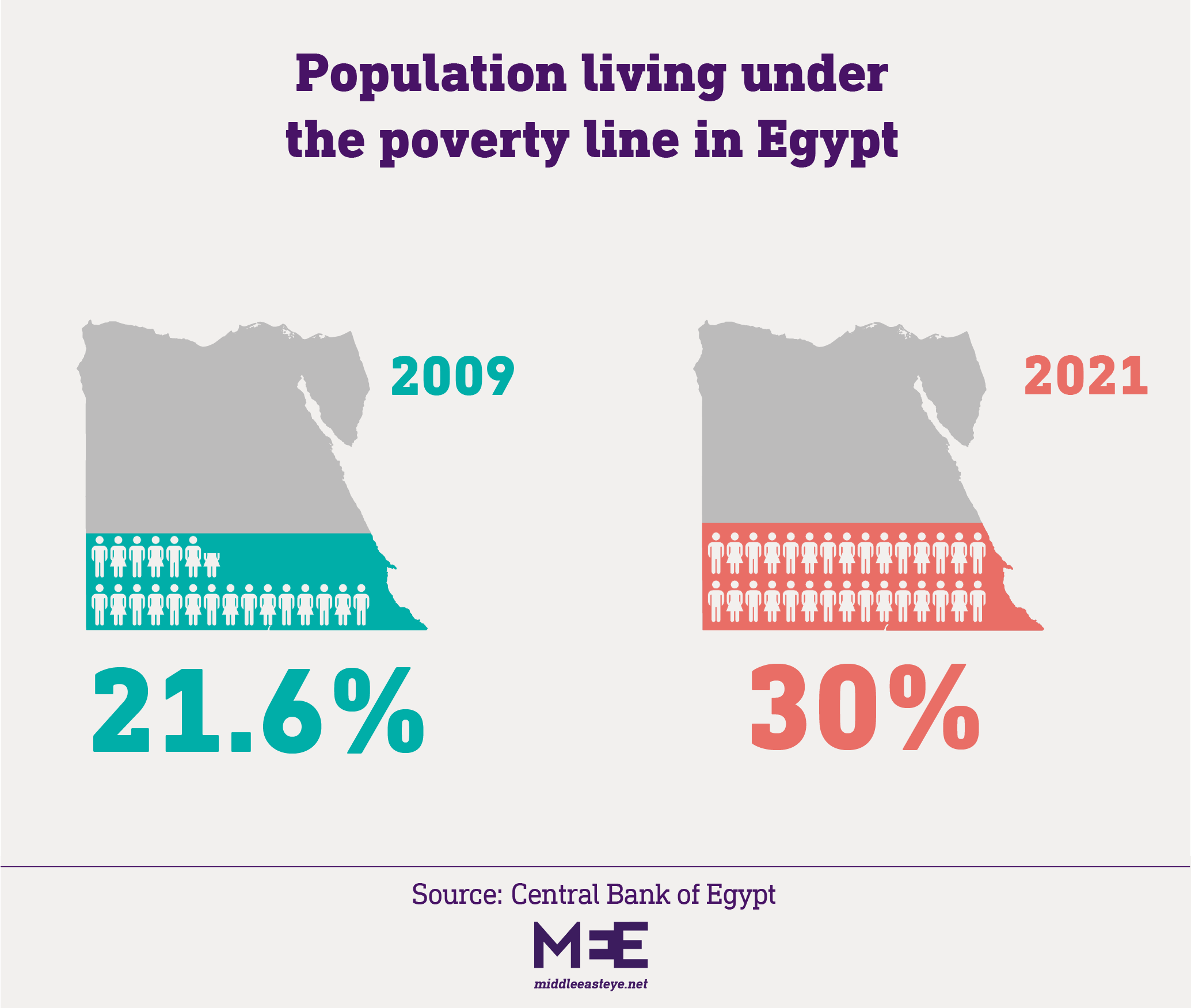

But these seemingly positive indicators obscure a much more complex picture, where a combination of domestic and international factors are set to deepen Egypt’s already high levels of poverty, with the rate currently sitting around 30 percent.

The most notable factor is the regime’s ongoing neoliberal dogma and insistence on eroding social supports for the most vulnerable, including the reduction last summer of bread subsidies used by 67 million Egyptians - a move expected to push millions more people into poverty. Another relevant policy, announced last December, is the exclusion of newly married couples from the food subsidy system.

The reduction in social spending has been combined with a regressive taxation system, which shifts the tax burden onto the shoulders of the poor and middle classes, ultimately lowering living standards for most Egyptians.

Chronic issue

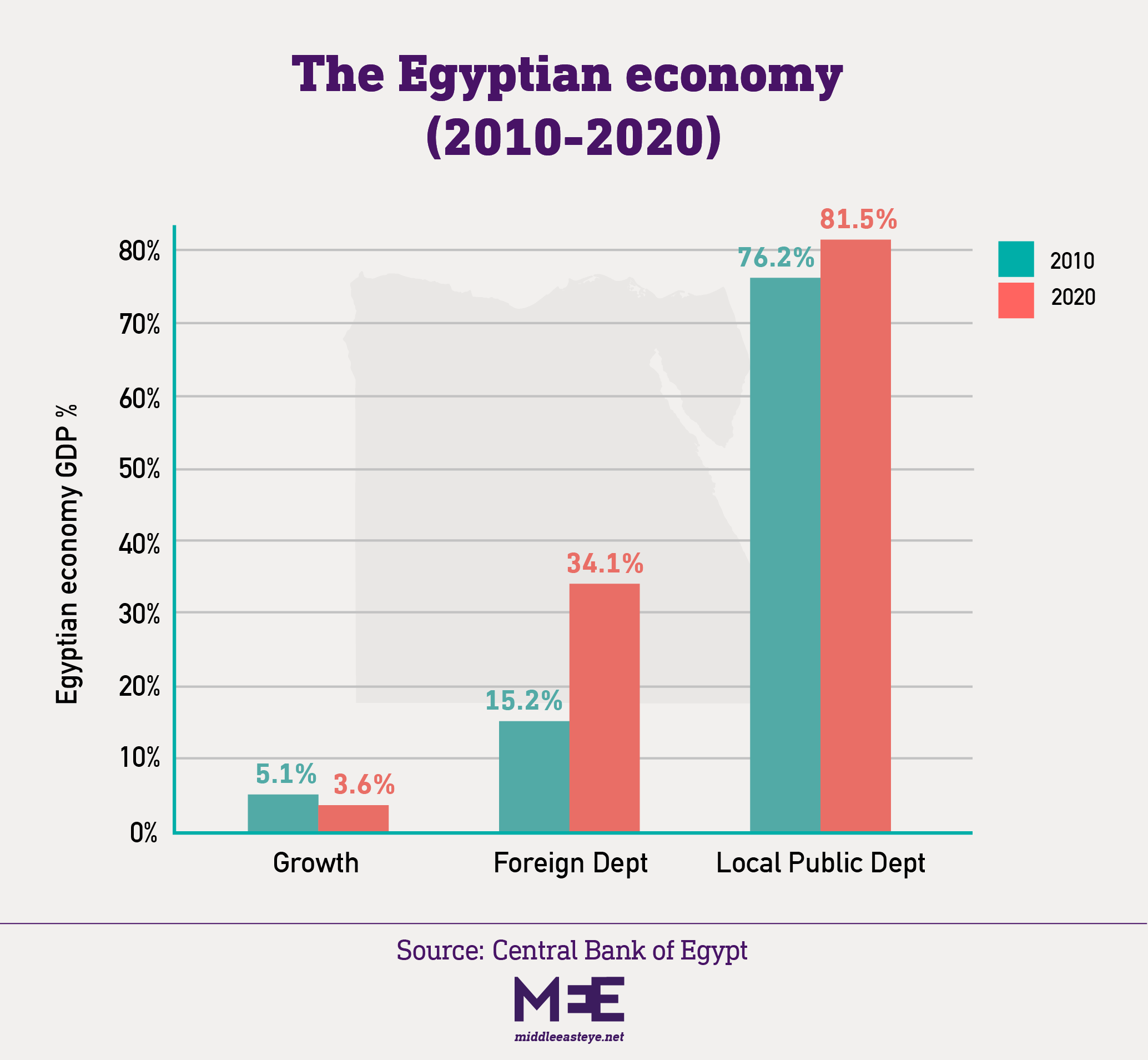

The regime’s neoliberal ideology is compounded by its failed, debt-driven growth model, which aims to improve Egypt’s international competitiveness and has placed pressure on the value of the Egyptian pound. Despite non-oil exports hitting a historic high in 2021, Egypt’s current account deficit reached 4.6 percent last year, almost double the value of 2018.

This has been a chronic issue for Egypt’s economy, and the regime’s focus on mega-projects as a driver for growth has not remedied the problem. The pound is currently overvalued by an estimated 16 percent, the highest overvaluation in Africa. This will have to be corrected at some point, which is bound to increase inflation, disproportionately affecting the poor.

The last currency devaluation in 2016 saw a sharp rise in inflation and a rapid increase in poverty rates. Although Egypt’s foreign currency reserves stood at $41bn at the end of 2021, giving the regime some breathing space to defend the currency, a devaluation seems inevitable.

The debt-driven growth model has also increased Egypt’s vulnerability to global financial flows, especially since the debt has not been used to bolster the international competitiveness of the Egyptian economy. The government relies heavily on debt denominated in foreign currency, which currently comprises more than a quarter of the overall debt burden. Only 60 percent of the foreign-denominated debt was issued externally.

This has several implications. Firstly, a devaluation in the value of the pound would increase Egypt’s public debt-to-GDP ratio. A devaluation of eight percent, for example, would increase the debt-to-GDP ratio by an estimated 1.8 percent. A more extreme devaluation could increase that ratio by 6 percentage points, pushing debt towards 100 percent of GDP.

Additional pressure

Secondly, the heavy reliance on foreign-denominated debt means that Egypt is affected by changes in interest rates in advanced economies. The expected increase in interest rates by the US Fed, for example, places pressure on Egypt to raise its own interest rates, already among the highest in the world.

The increase in debt and interest payments will place additional pressure on the state budget, where already a third of the budget is consumed by debt repayments. This pressure will translate into more cuts in social spending, which is bound to increase poverty levels, as the poor feel the crunch of international capital flows.

Finally, there are the impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, including on tourism and the increasing price of wheat. In 2021, tourism rebounded considerably in Egypt, with revenues reaching $13bn, back to pre-pandemic levels. This was partially boosted by a return of tourism from Russia, after the resumption of direct flights to Hurghada and Sharm el-Sheikh last August.

In February, before the outbreak of war, the escalation of tensions between Russia and Ukraine had already caused a significant drop - 30 percent - in bookings to Egypt from the two countries, and the escalation of the conflict is bound to prove disastrous for Egyptian tourism. Before the conflict, hundreds of thousands of Russians and Ukrainians were visiting Egypt each month.

Tourism is also an important source of hard currency in Egypt, meaning that any setback will affect not only those working in the sector, but also the regime’s ability to shore up the pound and pay its mounting debt, making a currency devaluation more likely.

Rising wheat prices

The picture is also complicated by a further increase in the price of wheat, already at its highest level since 2012, due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Egypt, the largest importer of wheat in the world, imported around $4.7bn in 2019, with Russia and Ukraine accounting for 55 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

A further increase in the price of wheat would thus create an additional burden on the Egyptian regime, and could accelerate the process of bread subsidy reduction, transferring the costs to the poor. The disruption in the market was already evident in February, when the Egyptian regime had to cancel a tender to purchase wheat after only a few offers at much higher prices were presented.

As the regime adapts by further cutting social spending ... the Egyptian poor are the ones who will ultimately pay the price

Hence, a combination of neoliberal ideology, a regressive taxation system, the structural failure of the regime’s growth model, the impacts of international capital flows, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine will act to impoverish the Egyptian masses even further.

The regime’s failure to invest in developing competitive industries, opting instead to invest heavily in infrastructure, has not only enriched the military elite, but also left the Egyptian poor vulnerable to the vagaries of international capital.

As the regime adapts by further cutting social spending, relying on financial support from regional allies, such as the UAE and Saudi Arabia, or borrowing even more from international markets, the Egyptian poor are the ones who will ultimately pay the price.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].