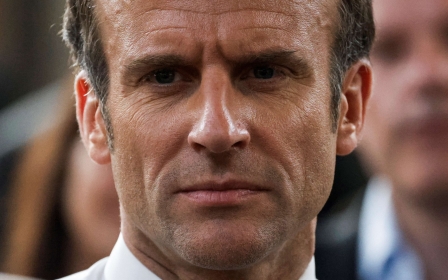

Return of Macron: Requiem for the French Republic

The results of the French presidential election were predictable, frustrating and historic in their catastrophic proportions. The second-round confrontation between Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen, ultimately won by the incumbent, showed that the traditional left-wing and right-wing parties that long dominated the country’s political establishment have been obliterated.

The Socialists earned just 1.8 percent of the vote, confirming that the party never recovered from the disastrous Hollande era and continues to pay dearly for its abandonment of the working class. The Republicans earned just 4.8 percent, as candidate Valerie Pecresse failed to break through with voters.

This rigged system, laid bare by the recent presidential election, has only exacerbated public defiance towards policymakers

Since former Republican President Nicolas Sarkozy pushed the concept of the “unapologetic right”, far-right topics have dominated the party’s agenda. This ultimately backfired with Macron’s arrival and his party’s absorption of moderates. Meanwhile, far-right polemicist Eric Zemmour stormed onto the political scene, contributing further to the mainstreaming of far-right narratives. Zemmour’s harsh criticisms of Le Pen had the opposite of their intended effect, making her more acceptable to a wider audience.

Leftist candidate Jean-Luc Melenchon earned a significant 22 percent of the vote, showing that his party’s strategy of endorsing local community organisers and launching massive voter-registration campaigns paid off. But this was not enough to convince a broader majority, and supporters say Melenchon could have done better if other left-leaning candidates had withdrawn.

Macron apparently failed to realise how unpopular he has become and what he represents to many, as a “president of the rich” who has “divided France”. For her part, Le Pen rode this wave of hatred, posing as the candidate who would protect the economy, even as observers noted that her programme would decimate the working class.

Pointless debate

Days before the second round of voting, Le Pen and Macron faced off in a presidential debate that received the lowest ratings since televised debates began in 1974. During the nearly three-hour event, Macron exchanged punchlines with Le Pen - and as is the tradition in French politics, they had to talk about Muslims.

Macron rightly criticised Le Pen over her suggestion to ban Muslim women from wearing headscarves in public. And yet, the president has done immense harm to the Muslim community through his own measures, such as the “anti-separatism” law, which violates Muslims’ freedoms of religion, assembly and speech.

As if the two opponents belonged to the same club, not one word was uttered about the McKinsey scandal that blew up on Macron days before the first round of voting, or on the allegations of fraud levied against Le Pen and her party (which she has denied).

The cringeworthy debate and the stakes of the second round of voting were perhaps best summarised by Olivier Madaule, a local leader with Melenchon’s LFI party: “It’s easier to vote for Macron if you don’t listen to him speak.”

The election results once again confirmed that the winning party was, by far, abstention. The widespread rejection of both Macron and Le Pen convinced around 26 percent of registered voters not to bother casting a ballot. At the same time, by coming so close to unseating Macron, Le Pen anchored herself in the mainstream for years to come.

Choosing the lesser evil

Democracy by representation is no longer appealing. Is France still a democracy? If so, is this democracy only about voting every five years? And is voting only about choosing the lesser evil? When will people be able to vote for something they truly believe in?

The current political regime in France has reached its limits. The Fifth Republic, which came about after Charles de Gaulle returned to power in 1958, is not adapted to the 21st century.

The president can appoint the prime minister, dissolve the National Assembly, resort to a referendum, and appoint three of the nine members of the Constitutional Council. He is also the commander in chief, and proving that the French Republic is more a compromise between a monarchy and a republic than a real republic, he is immune from prosecution.

Legislative elections will be held after presidential elections this year, favouring Macron’s party. And to seal the deal, France, like many of its western counterparts, suffers from a hyper-concentration of media ownership. This has further eroded whatever was left of French democracy, with no real counter-powers to the government.

This rigged system, laid bare by the recent presidential election, has only exacerbated public defiance towards policymakers. But if Macron and Le Pen have succeeded in one thing, it has been to convince more people than ever that elections do not change their lives for the better.

After all, it was on Macron’s watch that France made it onto the list of flawed democracies, while Le Pen would wipe out whatever is left of it.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].