State of terror: How the West helps Middle East dictators crush dissent

Post-1945, the United States defended its freedom and democracy by entering into a series of paradoxical partnerships with some of the most brutal regimes the world has known. US strategists believed that victory at the polls for communists would lead to suppression of democratic opposition and a one-party state. According to this theory, support for the rule of autocrats and military despots became essential if freedom and democracy were to be preserved.

Perhaps the most stark example of this Western complicity with state terror concerns the military coup that deposed Salvador Allende, the first Marxist to be voted into power in a South American liberal democracy when he became president of Chile in 1970. For Cold War Latin America, read today’s Middle East. For Salvador Allende, read Mohamed Morsi, the first democratically elected president of Egypt who was ousted in a military coup in 2013, just over a year after he was sworn in as president.

When I visited Cairo a few months after the coup, it was like attending a funeral. The atmosphere in the city was subdued, the streets were quiet. Protest was punishable by jail, torture was routine, and the acting president was a puppet while his defence minister General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi ran the country. Sisi’s picture was everywhere: in shops, in cafes, on street corners, often placed meaningfully alongside those of Nasser and Sadat, the country’s two previous strongmen. Sisi was rumoured to have told friends of a series of visions, some dating back decades, in which it was divulged to him that he was destined to emerge as Egypt’s saviour. And yet, to this day, not one British Foreign Secretary has uttered the phrase coup d’etat in relation to the events in Egypt. In a surreal interview on Pakistani TV, US Secretary of State John Kerry hailed General Sisi for "restoring democracy" and praised him for averting violence.

There are differences between Egypt and Chile. The political opposition to Morsi’s socially conservative Muslim Brotherhood presidency came from the country’s liberal left, while the hostility towards Allende came from the right. While Allende died by suicide on the day of the Chilean coup, Morsi died in prison six years after he was ousted from power. Also, the CIA was probably not a prime mover in the Egyptian coup, which was supported by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates with widespread support from neighbouring dictatorships.

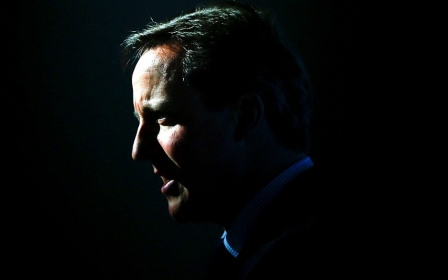

The similarities are nevertheless striking. In both Egypt and Chile revolutionary movements sought peaceful political transformation. In Egypt, the United States and the West offered little more than formal protests when the new Egyptian dictator went on to hunt down and kill more than a thousand political activists at Rabaa Square and al-Nahda Square in Cairo. This was around the same number as are thought to have been killed by the Chinese government in Tiananmen Square, although the media coverage was far more restrained, as is so often the case when reporting atrocities committed by a Western ally. The UK never protested about the conditions in which President Morsi was held in jail. President Sisi was in fact warmly received in Downing Street by David Cameron. The sale of British arms to Egypt continues.

Justifying the slaughter at Rabaa Square in 2013, an Egyptian army spokesman stated that "when dealing with terrorism, the consideration of civil and human rights is not applicable". Note the use of the term "terrorism" here. It was being used on behalf of an illegal military regime, which seized power in a military coup, to describe hundreds of pro-democracy protesters who had been shot down in cold blood. There were, once again, no complaints from the US or the UK. All this is familiar across the Muslim world: US and Western involvement in, or tolerance of, state terror and military coups.

Mohamed Ali Harrath: 'I was vilified'

The West’s often misplaced involvement in foreign regimes has shaped global politics over recent decades, but no less important is the impact it has had on the lives of individuals.

Mohammed Ali Harrath was born in 1963, close to the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid, where Mohamed Bouazizi would later set himself on fire on 17 December 2010, the desperate act which literally ignited the Arab Spring. Harrath came from an upper-middle-class family, which dispatched him to what he describes as a "rigidly conservative boarding school’"

Harrath became politically active at the age of 13. His first experience involved the preparation of news sheets to be pinned up on the wall of the local mosque. Of course, I asked: why the mosque? One of the central criticisms made in the secular West against so- called Islamists is their failure to distinguish between religion and politics. He gently explained that his local mosque was the only place you could agitate in the Western-backed dictatorship of Tunisia. There were no free newspapers, no political parties, no freedom, no democracy.

“I was fascinated by the power of the word,” Harrath told me. “I always believe the word is stronger than the bullet. Sometimes the bullet can silence the word, but then the word prevails.” He was arrested for the first time at the age of 18, while a student of textile engineering in Tunis, for “degrading the status of the president”. He became a founder of the Front Islamique Tunisien (FIT), formed in opposition to the Habib Bourguiba regime.

He spent most of his twenties on the run, in and out of jail. He told me that “the prison is not the problem. As bad as it is, it cannot be compared to when you go through investigation.” That meant being sodomised with sticks and bottles, with faeces being shoved into your mouth. Victims suffered mock-drowning and electric shocks. Amnesty International has described how some victims were tied to a chair for a week with an apparatus that pierced their neck with a needle whenever their head dropped through exhaustion. “We were unable to go to the toilet on our own,” Harrath remembered, “so we were carried by four or five friends.” He knows of 30 people who died under Tunisian government torture. When Bourguiba was removed from power in a coup in 1987, Harrath was on death row, facing execution.

Bourguiba’s successor, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, promised reforms. Rather than being executed, Harrath was freed. But that moment of hope proved a false dawn. Ben Ali turned out to be even more oppressive than his predecessor.

Harrath told me that at this point, after a decade of struggle, he reassessed his life. He said there came a moment when he realised there was no point fighting the regime in Tunis because Bourguiba and Ben Ali were just puppet rulers. The real enemy, he realised, was France, the former imperial power that provided security assistance and (in part through the European Union) diplomatic and economic backing to keep the dictatorship in power. This was the same insight which famously occurred to Osama bin Laden on his journey from Saudi dissident to terrorist chief. Bin Laden recognised that his real opponent was the "far enemy"– the United States. Rather than copy Bin Laden’s bloodthirsty logic, Harrath abandoned the political struggle and left Tunisia for good.

For five years, Harrath wandered the globe using false documents, “with a new name and personality every week”. When he arrived in London in 1995, he studied for a degree in politics at the University of Westminster, writing his undergraduate dissertation on Karl Marx (“good on the analysis but bad on the solutions” was Harrath’s verdict), and started to dabble in business. “I was working here and there, buying and selling – I did everything.” This nomadic period was to be used against him by critics who repeated Tunisian government claims – as usual with no evidence – that he worked with al-Qaeda.

For 15 years, Harrath lived the life of a political exile. Then, in 2004, he set up Islam Channel, a British TV station aimed at Muslims. It was then, he says, that the harassment began: “I was vilified.” First to visit, he told me, was the Inland Revenue. “They came here and stayed for nearly a month going through every single receipt, every single paper. What astonished me is that they were asking politically motivated questions. They are asking about our content, they are asking about programmes. They are the taxman, they have to see whether we are paying our taxes or not. But they went further than that.”

‘I have been called an extremist, an Islamist, a terrorist, all

the -ists’

- Mohammed Ali Harrath

Then the press attacks started. The British media had an easy task. When Harrath fled Tunisia, the Ben Ali regime had accused him of “counterfeiting, forgery, crimes involving the use of weapons/explosives, and terrorism”. His torturers asked for him to be added to Interpol’s Red Notice list, a system of international alerts aimed at detecting suspected criminals or terrorists. The international police agency obliged.

This meant there was no legal risk for journalists in connecting Harrath with terror. Interpol, such a respected international law enforcement organisation, had done the job for them. And no journalist took the trouble to look behind the Interpol designation to the regime that had demanded it. From this moment on, Harrath was fighting battles on two fronts. The Tunisian government and the London media shared a common interest in labelling him an extremist. In 2009, he spoke at a City Hall-sponsored event in London. The Sunday Express responded with a story headlined: “Boris terror link”.

The Times launched an innuendo-filled campaign, opening itself up to the charge of doing Tunisian dictator Ben Ali’s job by highlighting Harrath’s alleged links to terrorism, while asserting that he was an adviser to the Metropolitan Police. “[It] was part of the vilification,” he says. “It was aimed at damaging me within the community.” Harrath insists he was never a police adviser and the claim was based on his having spoken from time to time, like many other Muslims, to the Muslim Contact Unit of the Metropolitan Police. This did not stop the Conservative Party’s shadow security minister Baroness Neville-Jones demanding in 2008 that he should be sacked from his non-existent post. In deference to the Ben Ali regime, Neville-Jones declared that “the Tunisian government, an ally in the fight against terrorism, has asked for extradition of this man”. The Tories, then in opposition, were displaying a shocking readiness to operate within parameters set for them by a North African dictatorship. Ben Ali was then one of the most notorious rulers in Africa. Harrath had fled the country to escape him.

Apparatus of repression

In April 2011, remarkably soon after the fall of Ben Ali, Interpol removed its Red Notice, telling Harrath that, “after re-examining all the information in the file”, the organisation “considered that the proceedings against you were primarily political in nature”. Interpol has questions to answer. For almost two decades, its system of Red Notices had been used by Tunisia’s Ben Ali to harass and torment a leading dissident. Within a few months of the fall of Ben Ali, the Red Notice was removed. The agency’s purpose should be to help national police hunt down criminals, not to help round up opponents of dictatorship.

There were some powerful grounds for criticising Harrath. His channel broke Ofcom’s impartiality rules, and one employee won an appeal for unfair dismissal and gender discrimination. More seriously, it broke the broadcasting code by allowing a presenter to condone marital rape and violence against women.

But not one of the newspapers that so eagerly played up Harrath’s alleged terrorist past apologised – or even reported that Interpol had lifted him off the Red Notice list. Like the Conservative Party, they were happy to act within the parameters set for them by a dictatorship. Here was a man who arrived in the UK as a refugee from tyranny. Instead of being welcomed, he was treated like a criminal. For years, he has been unable to travel without risk of arrest and extradition. After he set up Islam Channel, a television station popular among the UK’s two million Muslims, Harrath’s fugitive status was ruthlessly used against him by a new set of persecutors: critics of Islam within the British political and media establishment.

Harrath, who sported a dark, bushy beard, joked: “I have been called an extremist, an Islamist, a terrorist – all the ists.” It wasn’t really a joke. Millions of innocent Muslims (and many non-Muslims) are categorised in the same way. Across much of the world, it is actually hard for any supporter of political freedom to avoid being labelled a terrorist. Even if they protest peacefully, they risk arrest and torture, or being shot down by armed police in the streets. If they flee their country, they can find themselves listed as terrorists or hunted down.

I have talked to scores of such ‘Islamists’ in the near two decades I’ve spent researching this book. They are brave and principled in a self-sacrificial way that nowadays we rarely encounter in the West, with high standards of personal integrity and public conduct. Otherwise they would not be able to endure torture and enforced exile for their beliefs. But, according to normal discourse in the West, these Islamists are single-minded fanatics hell-bent on the destruction of (to use the phrase much loved of British and American leaders) "everything that we stand for’" This is false, insulting and, above all, ignorant.

I have found again and again that supporters of political Islam revere the UK and even more so our institutions: Parliament, the rule of law, freedom of the press. Indeed, they admire them all the more keenly for the powerful reason that such institutions can scarcely be said to exist in their own countries and they understand rather better than we do how much they matter. It is true that they criticise the UK (and the West), but this is not because they want to destroy our values, despite what politicians and opinion-formers have repeatedly asserted. They criticise us mainly because we don’t cherish our values enough. Our newspapers spread lies and act as propaganda tools. Our governments break the law. Western intelligence services encourage illegal detention and torture. Our armed forces maim and kill with impunity and, in an especially cowardly way, through the use of drones and air power.

Worst of all, the UK is part of the apparatus of repression in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and elsewhere. We supply arms and provide advice and training for the police and security forces in regimes dedicated to the suppression of democracy and freedom. This means that their opposition becomes our opposition as well.

This explains one reason for hostility towards Islam in the UK. Regimes in Muslim states such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE devote time, influence and, above all, money to discrediting political movements that challenge them. In particular, they have been successful at portraying Islamism as a mortal threat to the West, often defining Islamists as terrorists, thus tying their Western allies closer through a shared enemy.

Photo: A poster of Mohamed Morsi at a supporters camp destroyed by the army during the Rabaa massacre in August 2013 (AFP).

The Fate of Abraham: Why the West is Wrong about Islam is published on 12 May by Simon & Schuster. Peter Oborne won best commentary/blogging at the Drum Online Media Awards in both 2022 and 2017 for articles he wrote for Middle East Eye. He was also named as British Press Awards Columnist of the Year in 2013. He resigned as chief political columnist of the Daily Telegraph in 2015. His latest book, The Assault on Truth: Boris Johnson, Donald Trump and the Emergence of a New Moral Barbarism, was published in February 2021 and was a Sunday Times Top Ten Bestseller. His previous books include The Triumph of the Political Class, The Rise of Political Lying, and Why the West is Wrong about Nuclear Iran.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].