'Terrible things happened here': The battle for Egypt's collective memory

Less than a decade after Egypt’s 2011 revolution, Tahrir Square underwent a massive facelift. Starting in September 2019, authorities invested around 150 million Egyptian pounds ($9m) to remove all memories of rebellion. Buildings were repainted, hundreds of palm trees were planted, and a new centrepiece was installed: a towering, 3,500-year-old obelisk from the time of King Ramses II, along with four sphinxes from Luxor’s Karnak Temple.

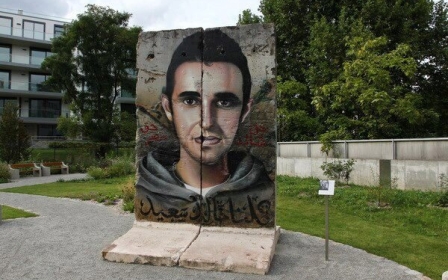

Many residents saw these efforts for what they were - a clear attempt to bury the recent past. The uprooted antiquities aimed to draw public focus away from the square’s symbolic meaning, while the fresh coats of paint covered any remaining traces of the revolutionary murals and graffiti that had been daubed across building walls.

'The streets were literally covered with our marks, and it gave us agency'

- Bahia Shehab, artist

“Since 2013, there has been a systematic effort to erase all collective memory of the revolution, and graffiti played a major part of that,” Bahia Shehab, a Lebanese-Egyptian artist and historian, said.

“[The graffiti] was a visual translation of how people were feeling … The streets were literally covered with our marks, and it gave us agency, and it gave us a feeling of belonging - and it made us feel as though the city was ours for a change.”

Today, the walls of Cairo that were once awash in colour remain largely blank. Shortly after the 2013 Egyptian coup, new legislation was implemented to criminalise graffiti with a maximum jail sentence of four years and a hefty fine. Iconic graffiti walls were knocked down. Artists were hounded from the streets, with many retreating into exile or landing in jail. It was almost as though the very act of remembering the revolution had been banned.

Whitewashing Cairo

For 18 days starting on 25 January 2011, Tahrir (“Liberation”) Square was transformed into an epicentre of nationwide protests demanding systemic change. Instead of cars and traffic fumes, the square was choked with people raising their voices against the 30-year autocratic rule of then-President Hosni Mubarak. With colourful banners, murals and chants, protesters claimed the public space as their own, ultimately leading to Mubarak’s resignation on 11 February 2011.

But the ensuing celebrations were short-lived. Egypt’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, took office in June 2012, only to be deposed a year later in a coup led by General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. In August 2013, Egyptian security forces slaughtered hundreds of protesters who had gathered at Cairo’s Rabaa square to denounce Sisi’s seizure of power.

The human rights situation spiralled further, with Sisi’s rule seeing an escalating militarisation of public spaces, including an anti-protest law and a wide-ranging crackdown on political dissidents. In a 2018 speech, Sisi declared: “That which happened seven or eight years ago will never happen again in Egypt.”

Armed with buckets of paint, surveillance cameras and draconian legislation, the new regime has worked diligently to whitewash Cairo’s colours. The ancient relics in the centre of Tahrir Square demarcate a space that is no longer public. It has become the site of a battle over Egypt’s collective memory, with revolutionary graffiti supplanted by symbols of the regime’s power.

'A Thousand Times No'

Shehab says she was first inspired to pick up a spray-paint can in November 2011, after witnessing the military’s violent clampdown on protesters in the weeks and months following the uprising. Unwilling to simply play the role of historian anymore, she wanted to express herself directly through graffiti.

“Unlike other artists who have a big group with them or would spend months on the streets painting large murals, I always worked alone … I always create very quickly using stencils, so I would never spend more than a few minutes on one wall,” she explained.

One of her best-known projects, titled “A Thousand Times No”, incorporated a variety of stylised representations of the Arabic word for “no”. Before the revolution erupted, she was already busy collecting these images; afterwards, she was able to assign a purpose to each “no”. They coated walls across Cairo: “No to military rule”, "No to killing men of religion", "No to stealing the revolution."

Another slogan gained prominence after images emerged in late 2011 of the Egyptian army assaulting female protesters, including a young woman who had been stripped to reveal her blue bra. Alongside “No to the stripping of the people”, stencilled images of a blue bra proliferated across the city.

“The urgency to paint messages came when things got darker and more uncertain towards the end of that year,” Egyptian graffiti artist Mira Shihadeh said.

'A sense of helplessness'

The use of sexual violence as a tool to police public spaces has long been used in Egypt to terrorise female journalists and activists into silence. In 2013, Human Rights Watch pointed to an “epidemic” of sexual violence in Tahrir Square, reporting dozens of mob attacks against women in less than one week. Women have also been detained by Egyptian military forces, subjected to “virginity tests” and threatened with prostitution charges.

Shihadeh described feeling “a sense of urgency and helplessness” at the time. She painted her first image, a woman’s face with a cross through her lips, in “as many places as I could”. Before heading to the streets, she practised the image over and over, until she could eventually draw it in two minutes with her eyes closed.

Another piece by Shihadeh, titled “The Circle of Hell”, refers to the coordinated nature of mob rapes, in which men form a circle around a woman to isolate her. She initially painted the mural on a wall on Mohamed Mahmoud Street on the second anniversary of the revolution in 2013. In the image, a woman, her eyes wide with horror, is engulfed by a sea of men with their teeth bared.

“There were reports of it happening in one corner of Tahrir … One report called it the circle of hell, so we called [the mural] that,” she said. “It took me an hour and a half to complete.” The mural remained untouched until 2016, when someone painted over the woman’s face.

Another Egyptian street artist known as El Zeft painted images of Queen Nefertiti wearing a gas mask, calling it a “tribute to all women in our beloved revolution” - many of whom donned gas masks ahead of clashes with police, but were subsequently chased from the streets.

'Spaces of connection'

Today, Shihadeh still practises art, but she has abandoned graffiti - partly out of fears that she could be arrested, but also due to her rising scepticism of its efficacy and concerns over how the international media has sensationalised the phenomenon.

“Street art is not instrumental in any revolution; justice would be. Until now, [political prisoners] are still in jail, so nothing’s changed,” she said. As more and more “random” artwork popped up on Mohamed Mahmoud Street after the uprising, she began to worry it was losing its impact.

“[I thought] this is wrong. Let’s not turn this into Disneyland,” Shihadeh said. “This street carries a lot of grief, and these artists are putting in random things … I feel quite possessive and protective about that, you know. These walls should say something more than something pretty. Terrible things happened here.”

While some of these works might have been only ephemeral marks on a wall, they also represented an enduring collective memory

Across Cairo, “the urgency or even enjoyment/excitement of graffiti is no longer apparent” today, she added. “It’s more popular as decorative commissioned work … in commercial spaces, with a bland message if any, and not on the street.”

Shehab’s artistic practice has also changed in the years following the revolution, morphing from the lonely work of stencilling walls in Cairo to large-scale, collaborative murals that she works on abroad. “When I lost access to Cairo, I started painting murals in different parts of the world,” she said. Several years ago, she worked with local artists in Britain to paint a mural at Lincoln University, with Arabic script reading: “We will not repent our dreams no matter how often they break.”

“I don’t think I’ll ever stop doing street art, even if it’s not in Cairo,” Shehab said, describing walls as “spaces of connection and conversations of the community”.

Her first stencils, hurriedly sprayed on the walls around Tahrir Square, were driven by the same compulsion to generate dialogue. And while some of these works might have been only ephemeral marks on a wall, they also represented an enduring collective memory - one that the regime can never paint out of existence.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].