What's left of the Egyptian revolution?

Egypt's 25 January revolution remains one of the greatest political events of the past century in the Arab world and perhaps beyond. Despite all critiques, there is no event comparable to it, in terms of both magnitude and impact.

When Tunisians succeeded in overthrowing their regime on 14 January 2011, their Egyptian brothers and sisters shared their elation at having disposed of one Arab tyrant. At the same time, they felt resentful that they themselves had been under the rule of the same man since 1981.

The people want

Social media and satellite channels were able to transmit what was happening in Tunisia at lightning speed and brought scenes of the revolution into every Arab household, shaking a false stability that was based on the naked power of repression and brute force.

The Tunisian revolution spontaneously began in rural areas in the depths of Tunisia before moving to Sfax, the country's second-largest city, and from there to the capital Tunis. The revolution began with socio-economic demands for development and employment before taking on a political character that produced the famous slogan: "The people want to overthrow the regime."

In reality, the coup against the Egyptian revolution began from the very first day of the revolution itself

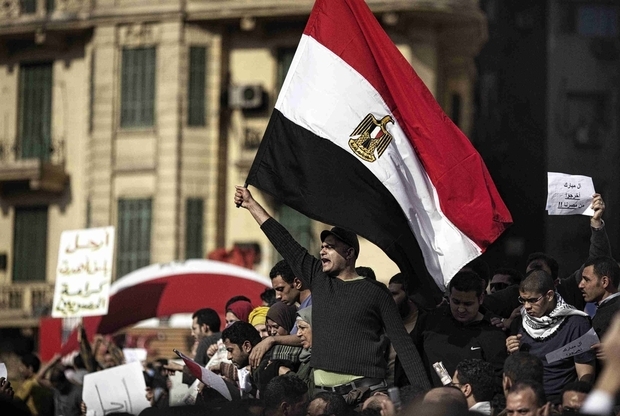

In contrast, the Egyptian revolution was born in the heart of the capital, Cairo. Its epicentre was Tahrir Square, from which it spread to other major Egyptian cities, which then created their own Tahrir Squares, from Alexandria to Giza.

The revolution carried a clear political demand from the very beginning. Egypt's educated and politically conscious youth were the engine of the 25 January revolution, combining organisation with a high degree of politicisation.

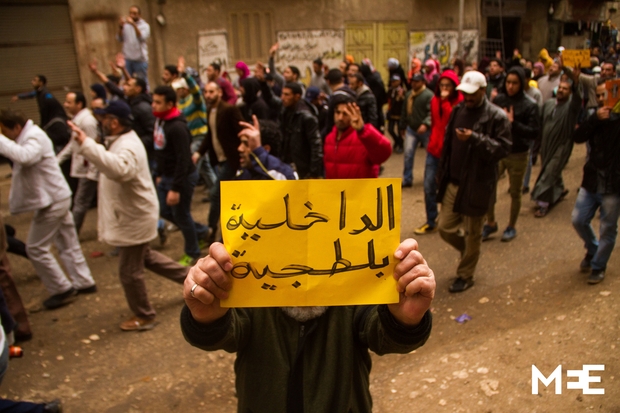

Despite attempts by Mubarak's men and the Military Council to divide and fragment them by opening channels of dialogue with some activists while simultaneously using violence and intimidation to end the Tahrir Square sit-in, Egyptian youth maintained their unity and goal - the end of the Mubarak regime.

The most famous images of the revolution are those of Mubarak's army of thugs and barbarians attacking protesters astride camels, carrying swords and sticks.

They failed to disperse the protests and Egypt's youth remained in the streets until they achieved their goal. This was finally achieved on 12 February when Omar Suleiman, then Mubarak's head of the intelligence services pronounced: "President Mohamed Hosni Mubarak has decided to step down from power."

A golden opportunity

In reality, the coup against the Egyptian revolution began from the very first day of the revolution itself. It began with the propagation of the misleading notion that the revolution was made by the army and the people together, and then by the Military Council's takeover immediately after the removal of Mubarak and its management of the transitional phase.

The Egyptian army considered the 25 January revolution a golden opportunity to reposition itself after having disposed of Mubarak, who had become a burden on the military.

Even when the army was forced to hold elections in May 2012, it turned out to be a mere tactical redistribution of power within the same old system of governance, allowing the military to continue to hold on to all the levers of power, even if they were forced to operate behind the scenes.

The 3 July coup, however severe its brutality and repression, cannot hold back the future of Egypt and the entire Arab world

At a time when political and revolutionary forces should have been working to build a united front to ensure the transfer of power to a civilian authority and the return of the army to their barracks, instead they were preoccupied with the struggle for power and positioning themselves for the forthcoming elections.

This was compounded by the deep polarisation between Islamists and secularists, and the widening gap between revolutionary youth and the Muslim Brotherhood.

Going to elections was not a mistake in itself but doing so under the supervision of the military and within the framework imposed by the army only served to deepen political wrangling and put the Egyptian revolution on a sure path to destruction.

It eventually became apparent that the army had only somewhat relaxed its grip on power after the 25 January revolution under the pressure of the street but began gradually to re-tighten it until the revolution was fully stifled by a full-fledged coup on 3 July 2013.

A gloomy reality

This coup was simply a continuation of the smaller coup that had begun with the announcement of the takeover of the military junta after Mubarak's removal.

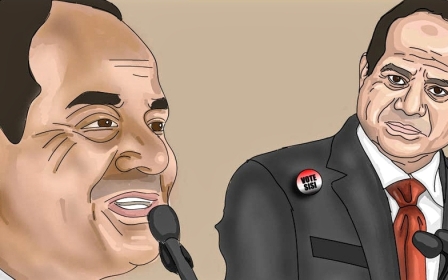

Today, the counter-revolution has tightened the noose on the 25 January revolution, besieging the Egyptian people with a brutal military apparatus led by Abdel Fattah El Sisi.

But what remains today of the 25 January revolution? Is it true that what was falsely called the "30 June revolution" has irreversibly crushed the 25 January revolution?

Observers of the Egyptian scene are faced with a gloomy reality on all levels, such that the Mubarak era now appears like a lost golden age. Nevertheless, the 25 January revolution is still alive in the minds of Egyptians and their consciousness of their right to freedom and dignity after having seen their own ability to break the wall of fear and overthrow a dictator.

Most of all, they have discovered that a despot they had thought was a pharaoh had turned out to be nothing more than a paper tiger.

It is true that Egypt has witnessed a huge regression but in terms of individual and collective consciousness, it is no longer possible to go back to square one.

The 25 January revolution introduced a new dynamic into Egyptian and Arab reality, despite the fierce resistance of the army and counter-revolutionary forces. Sooner or later, this new political consciousness and this rejection of dictatorship will translate into real acts on the ground.

The counter-revolution, however vast its power to repress, contain and misinform, will ultimately be unable to obstruct the path of history. The 25 January revolution was stopped in its tracks when it accepted the lie that "the army and the people are one hand".

Today, everyone knows that the cycle of revolution will inevitably complete its course towards the handover of power to civilian forces that express the will of the people and the return of the army to its barracks.

The 3 July coup, however severe its brutality and repression, cannot hold back the future of Egypt and the entire Arab world.

- Soumaya Ghannoushi is a British-Tunisian writer and expert in Middle East politics. Follow her on Twitter: @SMGhannoushi

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

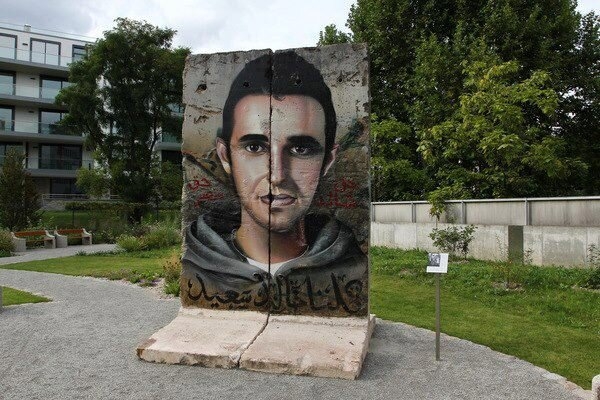

Photo: An image of Khaled Said painted on a fragment of the Berlin Wall by Andreas von Chrzanowski (Twitter / @wustelbalad)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].