Lebanon's Muslims locked out of Hajj by rising costs and collapsed lira

For every Lebanese Muslim who wished to perform Hajj this year, the 97th verse of the Quran’s third chapter has meant a great deal: “Pilgrimage to this house is an obligation by God upon whoever is able among the people.”

Since Lebanon was engulfed in a terrifying economic crisis in 2019, tens of thousands of Lebanese have found it increasingly difficult to perform this holy ritual.

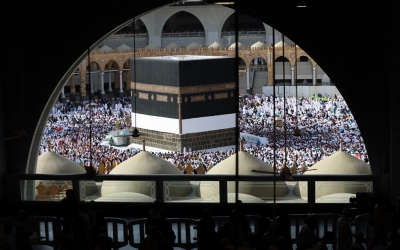

With Hajj scheduled to begin on Thursday, Jihan Tabarra, who owns a small fishmonger's, sits in her living room watching the Mecca channel, a Saudi TV station that streams live coverage all year round from the holy city. When footage of pilgrims circumambulating the Kaaba appears, the 52-year-old turns with a sad smile to say: “I was supposed to be there.”

Tabarra has been saving money in a Kaaba-shaped savings box for four years, so that she could fulfil the obligation expected of all able-bodied Muslims.

“I never had a bank account," she tells Middle East Eye. "I never trusted banks and I preferred to keep my money where I can see it. My only mistake was that I saved my money in Lebanese lira.”

Since 2019, the lira, which was once pegged to the dollar, has lost 93 percent of its value. Corruption, bad governance and an economy run like a ponzi scheme have plunged Lebanon into what the World Bank calls one of the worst economic crises in 150 years.

Tabarra never suspected that the currency could crash like it has, and now her savings aren’t enough to meet her family's basic needs, let alone for her to perform Hajj.

“Today, if I had to sell all my jewellery and my furniture it wouldn’t be enough for me to perform Hajj. I never thought I will be one of those who will not be able to be among the people, as the verses says. But the situation has never been worse,” she says. “But God will forgive me. However, I wish God won’t forgive those who deprived me from this blessing.”

Unaffordable costs

Like others worldwide, Lebanese Muslims have been restricted from performing Hajj over the past two years due to the pandemic. After two years of allowing only Saudi residents to perform the pilgrimage, Saudi Arabia is now allowing a million pilgrims from across the world to travel. In 2019, 2.5 Muslims performed Hajj.

For two years, the applications of Lebanese and Palestinian refugees submitted to the Hajj and Umrah Authority in Lebanon have been piling up, due to Saudi Covid restrictions. Around 24,000 applications were registered in 2022, but the quota of pilgrims allowed from Lebanon is decreasing.

According to Ibrahim Itani, an official at the Hajj and Umrah Authority, 15,000 Lebanese and Palestinian pilgrims were allowed to enter Saudi Arabia in 2019, which included 5,000 complimentary slots for Lebanese government officials.

“This year, due to Covid restrictions and despite the higher limit, Lebanon was given 45 percent of its original quota prior to the pandemic - 3,300 pilgrims for both Lebanese and Palestinians,” he tells Middle East Eye. “The shock was that Lebanon did not even reach the quota, and only around 2,300 pilgrims have made the trip.”

Itani says the economic crisis is partly to blame, but thinks other factors contributed too: alongside plummeting Lebanese purchasing power has been the rising cost of Hajj itself.

Nasser (who asks us not to use his real name) has been relatively unaffected by the crash of the lira. He’s paid in dollars, so his costs haven’t been affected, unlike hundreds of thousands of other Lebanese.

Despite that, the cost of Hajj has risen so much that Nasser feels it is still beyond his reach. “It seems even God’s duties are up for sale in Lebanon,” Nasser tells MEE.

Before 2019, the most luxurious trips to Mecca and the best pilgrimage services would cost around $3,500. Today, a basic trip stands at $6,000, with better services costing up to $12,000 for Lebanese.

“It is true that I am somewhat better off than many others, but I will not be ripped off in the name of God,” Nasser says.

As in other countries in the Middle East and North Africa, and the West before the system was chaotically altered at the last minute, Lebanese have to book their Hajj trips through travel agencies.

Saeb Kalash runs the Lebanese-Saudi Company of Hajj and Umrah, a travel agency specialising in pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia. He tells MEE that the rising price is due to extra fees set by the Saudi authorities due to new Covid regulations.

“The Saudi authorities have implemented new health insurance regulations that contributed to the increase in prices,” Kalash says. “Many transportation and other infrastructure services have been privatised since 2019, which helped raise the cost.”

Another reason for Lebanon’s failure to sell its quota is the problem in renewing passports. As a result of the economic collapse, authorities have adopted austerity measures in issuing new passports, because the finance ministry has been postponing money transfers to the international passport company contracted by the government.

“Many applicants who wished to participate this year had to renew their expired passports, and couldn’t get it on time,” Kalash tells MEE. The company that Kalash runs accommodated around 400 pilgrims in 2019, whereas this year it only catered to 100.

“The entire pilgrimage travel sector was hit hard. Our company is still one of the surviving ones… many other companies did not organise a pilgrimage campaign this year,” he says.

Corruption allegations

Many Lebanese are not buying the excuse that Covid regulations have meant extra expenses.

Lebanese attempting to apply for Hajj through travel agencies known to have better connections seem to have a better chance of being chosen to perform the pilgrimage, but those companies often charge a premium.

A sheikh, who preferred to remain anonymous, tells MEE: “This year’s pilgrimage season in Lebanon was nothing less than a black market. If you are connected within the right circles, you can have your applicants’ files processed. If you don’t, then you have to pay a black-market price.”

There is a discrepancy between the costs of new administrative fees and the new cost of Hajj overall, he says.

'This year’s pilgrimage season in Lebanon was nothing less than a black market'

- Lebanese sheikh

On social media, an anonymous campaign has begun, complaining about corruption in the Hajj application process.

A statement has been circulated online, titled “Hold the Hajj bandits accountable”, in a nod to the highwaymen who once robbed pilgrims; it describes the rise in prices as an “organised grand theft”.

“Some pilgrims had to borrow money and mortgage their jewellery to meet the extra fees requested by the companies,” it reads.

With discontent growing, the Hajj and Umrah Authority was forced to say that both it and the Saudi embassy had no part in the price increases. The rising costs, it insisted, were implemented by the tour agencies alone.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].