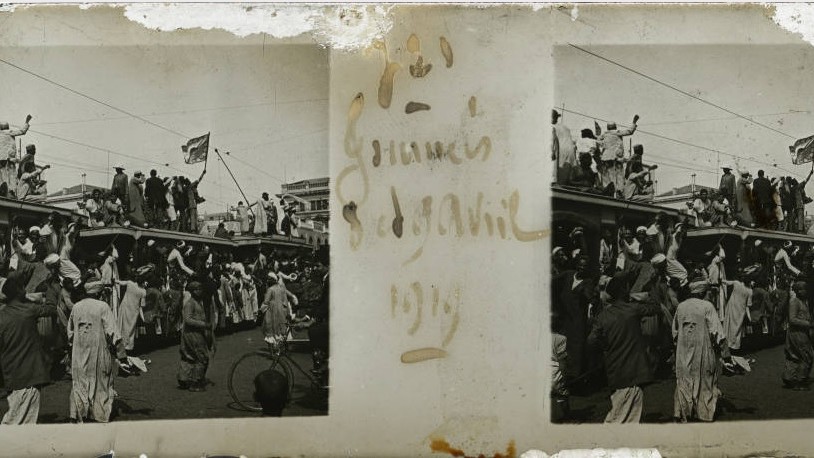

Egypt: New books challenge old narratives of the 1919 Revolution

In her exciting new book Egypt 1919: The Revolution in Literature and Film, Dina Heshmat has made an important contribution to our understanding of the origins of modern Egypt.

The story of the 1919 anti-British revolution - often considered the founding moment of the modern Egyptian nation-state - has been told and retold for more than 100 years.

Heshmat undertook close readings of 15 different cinematic and literary narratives of the revolution in Egyptian Arabic, and referenced dozens more for comparison throughout.

Plotting the stories chronologically, she found that each generation adapted the story of 1919 to fit with its own present concerns.

The dominant underlying refrain has remained focused on national unity, but the ways in which that unity is imagined and expressed have changed and been challenged at times by insurgent artists.

Reconceptualising the revolution

In her introduction, Heshmat intriguingly argues that the nationalist leader Saad Zaghl0ul and the demonstrations following his arrest in March 1919 have come to "signify" the revolution. This process of meaning-making groups a wide array of diverse political actions into a single category in order to help us build a coherent narrative of these monumental events.

By remembering and forgetting the revolution in different ways over the years, we have cultivated a popular memory of 1919 as a nationalist revolution led by the upper-middle class and centred on Cairo

But this signification process also deadens the voices of thousands of people who took part in demonstrations across the country, motivated by political ideals and imaginaries that might not fit into such a neat and tidy story.

By remembering and forgetting the revolution in different ways over the years, we have cultivated a popular memory of 1919 as a nationalist revolution led by the upper-middle class and centred on Cairo.

While Heshmat insists that it is not her purpose to rewrite the history of 1919, a substantial part of her introduction offers one of the most comprehensive synthetic accounts that I have yet seen. She reconceptualises the revolution as a period lasting from 1918 to 1923, distinguishing that moment from the specific movement triggered by Saad Zaghloul's exile and co-ordinated by the Wafd party.

This confrontation of forces included peasants and the urban working classes mobilising for their own agendas - including women from both groups - as well as co-operation and confrontation with Jews and Armenians.

In this sense, Heshmat's understanding of the revolution is similar to that of John Chalcraft in his magisterial 2016 book Popular Politics in the Making of the Modern Middle East.

One of the most important strands of popular protest during the revolution was driven by poor farmers in the countryside, especially the rural south.

Nearly 20 years ago, Peter Gran made the provocative suggestion that the patterns of inequality and exploitation favouring Egypt's populous northern cities at the expense of its underdeveloped south echoed similar dynamics in the history of Italian capitalism, as described by Antonio Gramsci.

The 'southern question'

This "southern question," that looms over the historiography of modern Egypt, has cultivated a historical common sense that what happens in the cities is what really matters.

Zeinab Abul-Magd showed proof of Egypt's southern question in her 2013 book Imagined Empires, through intensive investigation in the archival materials from the southern province of Qina.

She documented how the south was historically integrated into an Afro-Asian economic system oriented towards the Indian Ocean, and was never fully subjugated by the European-oriented north.

When the 1919 revolution took place, the people of Qina did not share in the romantic nationalism.

Similarly, in more recent research, historian Alia Mossallam suggested that a whole separate wave of political discontent triggered popular protest in southern Egyptian towns like Hamamiyya.

What Heshmat's book helps us understand is how such disparate elements, like the movements in Hamamiyya and Qina, can get subsumed into a totalising story about national unity centred on Cairo.

One of her most fascinating close readings comes when she comprehensively analyses an Egyptian high school history textbook. "Although the textbook does mention the oppression experienced in particular by peasants during the First World War," Heshmat writes, "there is no clear link between the peasant action during the 1919 revolution and this oppression."

The role of labourers

My book, The Egyptian Labor Corps, tries to make this link more explicit in order to more clearly distinguish the multiple political imaginaries and solidarities that animated popular protest during the 1919 revolution.

In particular, I think the story of the Egyptian Labour Corps can help to resituate the revolution in the context of the British Empire and the First World War. From 1914 to 1918, the British imposed martial law in Egypt and recruited approximately half-a-million young Egyptians to serve as military labourers in Europe and the Middle East.

They worked as stevedores on the docks of France and Italy, dug trenches in Gallipoli, and drove camels laden with supplies in the deserts of Libya, Sudan, and the Sinai. In the advance through Palestine and into Syria, which was the second-largest theatre of the war, Egyptian migrant labourers made up the bulk of the military labour force.

I found that mass recruitment for the Egyptian Labour Corps provided a crucial background for the 1919 revolution as it developed in the countryside. Although Egyptians served in battles against the Ottomans as early as December 1914, it wasn't until 1917 that forced recruitment really picked up.

I found that mass recruitment for the Egyptian Labour Corps provided a crucial background for the 1919 revolution as it developed in the countryside

When demand for young men to serve in the Labour Corps necessitated the recruitment of tens of thousands each month, the labour contracting system was simply not big enough to fulfil it. Hesitant to turn to the army, British colonial authorities relied on the system of village administration.

Reforms under the long decades of British administration had incorporated the 'umda or shaykh al-balad as an official village headman who could function as the pillar of the state in the countryside. One of the traditional responsibilities of the village headman was to provide labouring bodies to maintain state infrastructures during the Ottoman period.

In 1917, village headmen took over this role once again to provide workers for the Labour Corps. They themselves had, in most cases, come into their positions as a result of family connections.

For example, the famous writer Muhammad Husayn Haykal came from a family that, sometime in the early 19th century, gained the position of headman in the village of Kafr Ghannam, near Simbalawin, in the Delta province of Daqahiliyya.

They passed it to the next eldest male - brother to brother, rather than father to son - while the family acquired land and became wealthy in comparison to most of the farmers of their village.

In giving the village headmen quotas of labourers to recruit during the war, and looking the other way if they filled them by force, British officials accelerated already unequal power dynamics.

The power of the headmen

Village headmen could conscript their rivals, protect their sons, and accept bribes to exempt those who were able to pay them. Labour Corps recruitment became a deeply regressive, in-kind tax that the poorest young men of the countryside had to pay with hard manual labour.

My research in the British National Archives uncovered 35 reports of violent resistance to Labour Corps recruitment taking place across the country from May to August of 1918

It was not long before this led to confrontation. My research in the British National Archives uncovered 35 reports of violent resistance to Labour Corps recruitment taking place across the country from May to August of 1918.

The British archives include references to seven cases of mass resistance during the bloody summer of 1918. In the town of Talkha, in Daqahiliyya province, a crowd of 200 descended on recruiting officials, asking for the release of Muhamad al-Sayyid.

In Faraskur, 26 men who had been condemned to Labour Corps service staged a sit-in at the jail cells where they were being kept. A large police force was sent from the surrounding towns to crush the demonstrations, but the atmosphere of discontent was clear for all who had witnessed the events.

Nationalist leaders were aware of events like these, and many witnessed them first hand. Zaghloul was the son of a village headman from the Gharbiyya province, and he often returned to the countryside to check on his estate.

In a diary entry on 28 May 1918, Zaghloul mentions a draft riot that he personally witnessed "with many deaths and casualties". The date is significant here, as the decision to form the Wafd did not come until November that year.

The Wafd leadership must have recognised the crucial importance that support from the countryside could offer them, because one of their first acts was to circulate a series of petitions to various towns and villages acknowledging their public "deputyship" (tawkil).

The Wafd was an alliance between town notables, who were often village headmen themselves or their sons, and nationalist-inclined members of the aristocratic elite that had ruled Egypt for generations. They were successful in achieving broad-based support, especially from students, lawyers, government employees, and the shaykhs of al-Azhar.

But once the arrest and exile of Zaghloul and the Wafd leadership sparked a series of protests across the country, events unfolded at a rapid pace, and the Wafd movement struggled at times against developments that ran counter to their interests.

We can see this clearly in Asyut. By the late 19th century, Asyut had to some extent displaced the province of Qina, chronicled in Abul-Magd's expert work I mentioned before, as the "capital" of Egypt's south.

It was the first southern town to get a railway station, had a large Christian population including many missionary schools, and was the main transit point for African slaves into Egypt and the great Ottoman Empire.

On 15 March 1919, students and lawyers launched a protest movement in Asyut similar to the protests co-ordinated by the Wafd elsewhere. But events spiralled out of control. Protesters set fire to a huge barn stacked with hay requisitioned by the military authorities.

According to Egyptian historian Abdel al-Azim Ramadan, protesters surrounded the house of Mahmud Pasha Sulayman, the co-president of the Wafd's central committee and a former village headman in Sahil Salim. They sacked the house and set it on fire, shouting: "Has Muhammad Mahmud Pasha Sulayman ever given a loaf of bread to the hungry? We need food!"

By 22 March, railroads, telephone, and telegraph lines had been cut, and the primary means of co-ordination for both nationalists and the British colonial state was disrupted.

The myth of national unity

The nationalist historian Abd al-Rahman al-Rafi'i relates how local lawyers and notables from Asyut responded by forming a "national committee". They began patrolling the streets to "secure people's lives and money, and to prevent the efforts by some of the ruffians (ashrar) to go to the city for non-nationalist goals".

If you focus closely enough on specific spaces and places like Asyut, keeping attuned to their connections to broader transregional networks of empire, the myth of national unity in the historiography of 1919 starts to unravel

Reading against the grain, Rafi'i's account provides evidence of the existence of protesters who had "non-nationalist goals".

While he writes them off as "ruffians" (ashrar), this is perhaps indicative of Rafi'i's own class position as a member of the urban, educated nationalist movement.

Asyut seems to have been uniquely aggrieved by Labour Corps recruitment. Of the 35 incidents detailed in the British archives from the bloody summer of 1918, 12 of them took place in Asyut.

When the war ended and Labour Corps recruitment continued, the British complained of "scores of cases" in Asyut and Girga where recruiters encountered violent resistance.

During the 1919 revolution, Labour Corps officials were targeted in this region at the infamous Dayrut Train Massacre on 17 March and the killing of the head British recruiting inspector at Salsh days later.

The situation was only pacified by the deployment of a large military contingent consisting of planes from the Royal Air Force and a warship outfitted with armour and machine guns sent down the Nile.

If you focus closely enough on specific spaces and places like Asyut, keeping attuned to their connections to broader transregional networks of empire, the myth of national unity in the historiography of 1919 starts to unravel.

More research remains to be done at the local level to tease out the full flowering of political activity that took place during this unique historical moment.

An upcoming volume from Bloomsbury, The Egyptian Revolution of 1919: Legacies and Consequences of the Fight For Independence, promises to do some of this work by drilling down on different episodes throughout the revolutionary process.

I look forward to seeing how scholars and journalists engage with this new work.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].