China looks to the Gulf as power projection grows

Two recent events have drawn attention to China’s power projection overseas.

In early August, Chinese military forces conducted a series of drills in Taiwan following US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei, highlighting how it could surround and blockade the island if necessary.

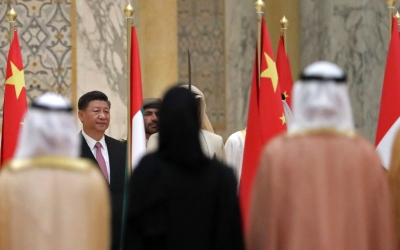

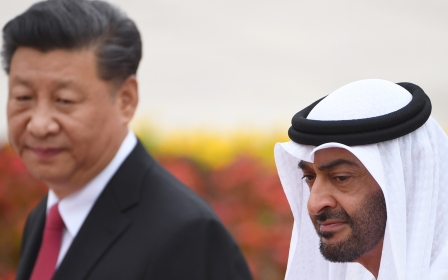

Days later, rumours emerged that President Xi Jinping’s first trip outside of China since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic might be to Saudi Arabia. The trip has yet to take place but would be of particular importance at a time when there are growing concerns about China building a network of dual-use ports throughout the Indian Ocean region.

The Chinese navy is committed to projecting great military power, which could be an asset to Gulf countries from a regional security standpoint

These seemingly unconnected events took place weeks after China launched its third aircraft carrier, the Fujian, in an effort to close the gap with the United States and increase its military power projection.

It was also the first carrier to be designed and manufactured domestically, and the most advanced, weighing in at 80,000 tonnes and featuring an electromagnetic catapult-assisted launch system.

What are the implications of this technological development for the Gulf? Could the carrier be a game-changer in the regional military balance of power? While in the long term, the Fujian will contribute to China’s efforts to expand the power of its naval force, its shorter-term effects may be more limited.

It will still be a few years before the Fujian becomes fully operational. Furthermore, owning and deploying an aircraft carrier can actually be a liability these days. In an era of hypersonic missiles, aircraft carriers have become increasingly vulnerable.

As US defence secretary, James Mattis asserted that the days of the carrier are over, arguing bitterly with the navy over their future. It was an argument Mattis lost at the time, but the wider debate continues.

Hypersonic weapons

China’s recent testing of hypersonic missiles has laid out a challenge for the West, which was picked up by the Aukus pact as Britain, the US and Australia committed to working together earlier this year to develop hypersonic weapons. It is clear that aircraft carriers, which analysts say present an “obvious target” in times of conflict, will not become the centrepiece of China’s foreign and military policy in the Gulf.

As China launches its new carrier, the navy’s focus remains on “large-scale military operations around its maritime periphery”, according to the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCESRC). In the near future, China will continue to face challenges, and it has a limited set of options in terms of military deployment.

The balance of military power in the Indian Ocean shows that the Chinese navy is outnumbered by the combined US, Nato and Indian naval assets. Thus, even when the new carrier is operational, Beijing will have to restrain its great power ambitions in the northern Indian Ocean and through the Gulf. These challenges intensify the further the Chinese navy operates from its home territory.

Of more interest to Gulf countries is the idea - as expressed by some western military analysts - that China might deploy its carriers against less powerful states or non-state-actor adversaries, similar to what the US did during and after the Cold War.

Indeed, in the coming years, China will seek to improve its expeditionary capabilities for “fighting a limited war overseas”, the USCESRC noted. This will have an impact on the Gulf, as the carrier will help China to more effectively protect its commercial interests and maintain stability.

Opposing hegemony

In late January, Chinese Defence Minister General Wei Fenghe said that Beijing and Riyadh should “strengthen coordination and jointly oppose hegemonic and bullying practices”. This came in the context of missile strikes by Yemen’s Houthis against the UAE, home to more than 200,000 Chinese residents.

Any intervention in such a scenario could potentially affect Beijing’s relationship with Tehran, and China’s cautious strategic culture means that any military action would be coordinated with local powers, so as not to interfere in their internal affairs.

Yet, its dependence on Gulf energy sources has made it vulnerable to supply disruptions and price spikes fuelled by conflict. This will compel China to adopt a bolder military posture when necessary, for practical reasons.

In this context, China’s aircraft carrier would be a key diplomatic tool that could be used to patrol waters around the Gulf, reassure partners, signal political-military resolve, and forge coalitions. At a time of American disengagement from the Gulf, this is exactly what China needs to do in order to secure regional partnerships.

China’s newly built aircraft carrier thus sends an important message to Gulf countries. The Chinese navy is committed to projecting great military power, which could be an asset to Gulf countries from a regional security standpoint, despite China’s diplomatic neutrality on contentious issues.

But the first truly modern Chinese carrier also shows that China’s efforts to build an overseas-capable navy remain at an early stage. China thus continues to display features of both a strong power and a weak one.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].