US-China: How 2022 saw the old world order start to crumble

It is highly likely that 2022 will be remembered as one of the 21st century’s pivotal years. It will sit alongside 2001 (11 September attacks), 2008 (the global financial crisis) and 2020 (the Covid pandemic).

It will be remembered as the first year after more than three decades where geopolitical risk could no longer be discounted in economic and financial considerations. Geopolitics matters and today it is far more of a consideration in the corporate sector.

Last year, the world began its tectonic shift from a post-Cold War unipolar order to a still undefined and uncertain multipolar one

Last year will probably be seen as a watershed, when the world began its tectonic shift from a post-Cold War unipolar order to a still undefined and uncertain multipolar one.

Over the past three decades or so, the global order has been built upon three main pillars: the US's undisputed hegemony; globalisation as its undiscussed economic order; and the US dollar as the uncontested global reserve currency and financial clearing house. Now they are all being questioned.

Evolutionary transition

In 2022, a three-decades-long party - with low inflation, low interest rates, low commodity prices and unrestrained money printing and massive quantitative easing - ended. The perspective is now different. Leadership and decision-makers appear clueless and disoriented, not to mention the people they govern. It is a state of mind described as zeteophobia: a paralysis in the face of life-altering choices.

According to Professor Barry Buzan, c0-author of The Making of Global International Relations, the so-called, and so far US-led, rules-based world order is enduring an evolutionary transition where "China, India and the Islamic world are reclaiming their cultural status… not just their wealth and power… but also [re]-acquiring the cultural autonomy they had lost”.

It is disgraceful, a real accident of history, that the conflict in Ukraine has been the catalyst for such “re-acquired cultural autonomy”. The net result has been a fractured global politics, which has placed the Global West and the Global Rest on two different tracks regarding the conflict and other global issues.

Nothing symbolised this divide better than voting patterns at different UN bodies regarding the conflict. The Global Rest did not buy the Global West’s narrative about the conflict being an inflexion point of history, where democracies are called to rally to face down the assault of autocracies. Nor did they buy the sanctions adopted to punish Russia.

Western-centric perceptions of world events have been utterly dismissed for the first time. A foreign minister from one of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) nations summed it up unequivocally: the problems of Europe and the US are no longer the problems of the whole world.

The dialectic between the Global West and Global Rest will be one of the main geopolitical drivers of the coming years, with the competition between the US and China as its cornerstone.

A realignment of the power balance around a BRICS-G7 confrontation is envisaged. There is a long list of countries keen to join BRICS. Most of them, curiously, are traditional US partners or allies: Argentina, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UAE.

The end of globalisation?

It was also the year that marked the abrupt end of three decades of Russia getting closer to the West. Who lost Russia in 2022, or why Russia lost itself, might become research topics for generations of historians.

As for the world order’s economic pillar, the least that could be said is that if Russian integration with the West is dead, then globalisation is not in good health. Some pundits have even written its obituary.

In the past decades, the world real economy has worked on two essential relationships: Russia supplying cheap energy to the EU; and huge trade flows between China on one side and the EU and the US on the other. The first is over, the second is under assault.

Russia's energy supplies are expected to drop to zero in 2023, and it is highly uncertain whether they will be restored anytime soon, or even if they will be restored at all. Any alternative, green or non-green, will be more expensive - a condition that might also affect the EU’s overall competitiveness.

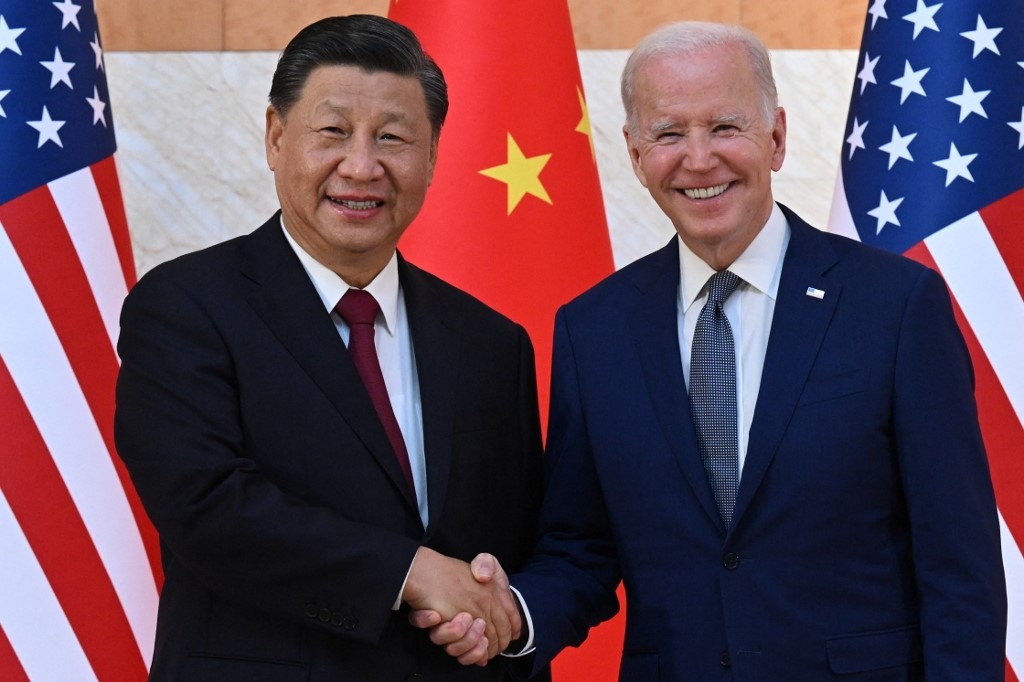

As for US and Chinese markets, some clouds are gathering. The US Inflation Reduction Act is recreating Transatlantic trade tensions, while the Chips and Science Act, signed into law last August by the Biden administration, resembles a technological war against China.

Effectively, in just one generation, China went from a poor peasant economy specialising in labour-intensive products to an advanced one, second only to the US

The US economy has boomed due to its trade relationship with China. America's corporate sector has largely outsourced production to China, making the latter the US's workshop.

Everybody was happy - the Chinese, with their soaring exporting volumes and for getting US technological know-how; American consumers, with their supply of cheap products purchased with cheap credit (low or zero interest rates); US corporations, with their enormous profits made through cheap Chinese labour costs; and, lastly, the US Treasury, with up to $1 trillion bonds subscribed by the Chinese government.

Now everything is at risk. According to US decision-makers, China is now the main threat that America will face in the 21st century, an assessment that, to a certain extent, is shared also within the EU.

Effectively, in just one generation, China went from a poor peasant economy specialising in labour-intensive products to an advanced one, second only to the United States. Beijing leads in 5G communication, batteries for electric vehicles and solar panels for renewable energy generation - not to mention artificial intelligence. All top sectors that will decide who will lead the fourth industrial revolution.

Europe's tough dilemma

There are increasing risks of competing trade blocs, causing turmoil in the commodities, energy and food markets, with possible further negative consequences for the global supply chains.

The debate about China’s threat is over in Washington, and there is no empirical evidence that could push the US establishment to review its assessment. In Europe, there are still mixed feelings.

In any case, in 2023 Europe will face a tough dilemma: align itself fully with the US narrative about the China threat and, consequently, review its posture in the same way it did with Russia and pay even direr economic consequences; or follow a more nuanced approach? This will be one of the most important geopolitical developments to watch.

An economic, financial and technological war between the US and the EU on one side and China on the other is the last thing the world economy would need at such a moment.

The world financial order is also under attack. The BRICS and some other countries aspiring to join (BRICS plus) are apparently determined to free themselves from an exclusively US-controlled system by using alternative currencies to the dollar and trade and financial networks alternative to the western-controlled Swift and US clearing houses for payments.

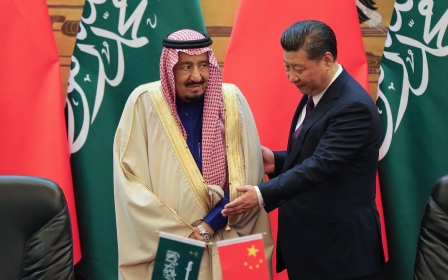

This apparently started with commodities trade, particularly in energy. China's President Xi Jinping recently paid a visit to Saudi Arabia, where he also met all the other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) leaders.

His speech laid the ground for the birth of the petro-yuan, aimed at competing with the petro-dollar. He proposed “a new paradigm of all-dimension energy cooperation” that in three to five years should strengthen Chinese-GCC energy cooperation in the upstream sector, in engineering services, as well as downstream, in transportation and refinery.

He even proposed the Shanghai Petroleum and Natural Gas Exchange as the platform for yuan settlement of oil and gas trade.

America's $31 trillion deficit

Credit Suisse’s analysts have drawn attention to the potential impact on the US dollar should all oil and gas sent to China be invoiced in renminbi. India, Russia and Brazil, now governed by Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva once again, might follow.

What might happen to the US dollar if the People's Bank of China, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the Bank of Thailand and the Central Bank of the UAE created central bank digital currencies enabling real-time, peer-to-peer, cross-border and foreign exchange transactions without involving the US currency and the network of corresponding banks run by the US dollar system?

How would the US manage its record $31 trillion deficit if not only opposing trade blocs but also alternative financial systems emerged?

How would the US manage its deficit, which this week peaked at $31.4 trillion, if not only opposing trade blocs but also alternative financial systems emerged?

This tectonic shift is now called the great power competition. Competition seems such a reassuring word. It evokes sport, an environment ruled by fair play, where the players shake hands after the game.

Global politics, unfortunately, takes place on a very different playing field. Conflicting interests might take a dangerous turn - and what we have been seeing so far is everything but fair play.

Rather, it seems more like a dangerous zero-sum game.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].