Libya: Cables reveal secret preparations for Haftar's visit to Russian aircraft carrier

Russia’s military attache in Saudi Arabia was the point man for talks between Khalifa Haftar and Moscow in the lead up to the Libyan commander's 2017 visit to a Russian aircraft carrier, according to documents obtained by Middle East Eye.

The cache of diplomatic cables between the Russian embassy in Saudi Arabia and a representative of Haftar show how Russia's Riyadh mission served as the regional liaison between the eastern Libyan commander, his emissaries and Moscow for high-level meetings, requests for arms sales and intelligence collection.

MEE obtained the documents from a Libyan source close to Haftar's circle and will publish further details later.

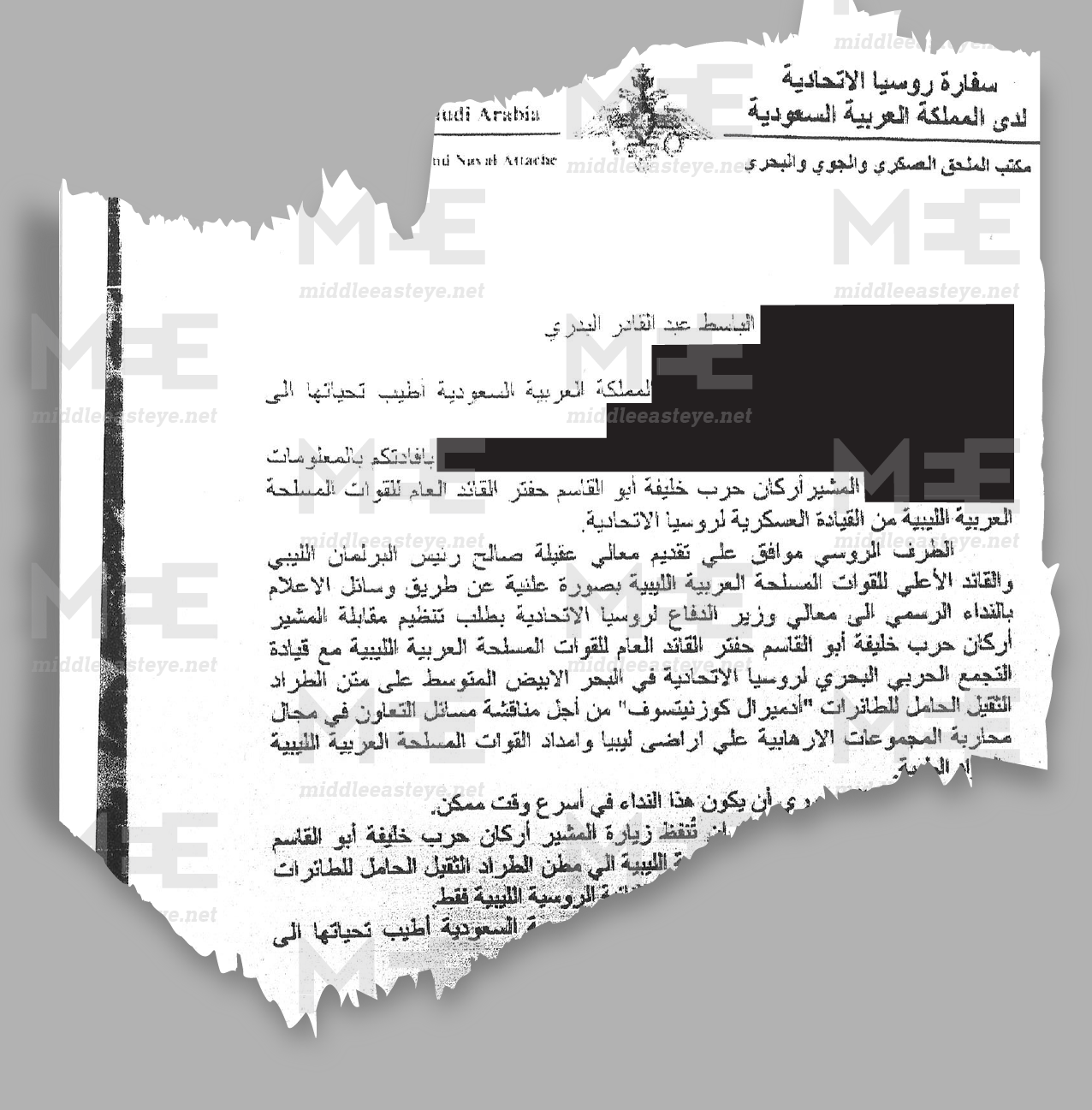

The cables detail how a visit for Haftar to a Russian aircraft carrier in January 2017 was facilitated to discuss “issues of cooperation in the field of fighting terrorist groups in Libya and supplying the Libyan Arab Armed Forces with medical supplies”.

Following the meeting, about 70 wounded soldiers from Haftar's Libyan Arab Armed Forces, a coalescence of militias also known as the Libyan National Army (LNA), were flown to Russia via Egypt for medical treatment.

The Russian embassy in Saudi Arabia did not respond to requests for comment.

The correspondence and trip to the Admiral Kuznetsov, Russia's only aircraft carrier, came at a time when Russia was stepping up support for Haftar. Then, like now, Libya was divided by competing governments in the east and west, and Haftar had designs to become the oil-rich North African country's leader - ambitions that resulted in a failed attempt to conquer Libya's west in 2019-2020.

Russia was already violating a UN arms embargo at the time by funnelling weapons to Haftar, and Moscow was also printing billions of dollars worth of Libyan banknotes for the Haftar-aligned government in Libya’s east. In 2016, Haftar visited Moscow twice, as his forces fought a gruelling battle for control of Benghazi.

MEE previously reported that after the aircraft carrier visit, during which Haftar spoke to Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu on a secure phone line, Russia agreed to boost its military support for the commander in coordination with Algeria.

On 4 January 2017, Haftar wrote personally to Shogui, accepting an invitation passed to him by Russia via its embassy in Saudi Arabia to come aboard the Admiral Kuznetsov.

“Accept from us our deep gratitude and courageous support of the Libyan people in their struggle against terrorism, in order for security and peace to prevail in Libya and the entire Mediterranean,” Haftar wrote.

The Russian coordinating with Haftar at the time was Colonel Vladimir Kirichenko, military attache at Russia's embassy in Saudi Arabia.

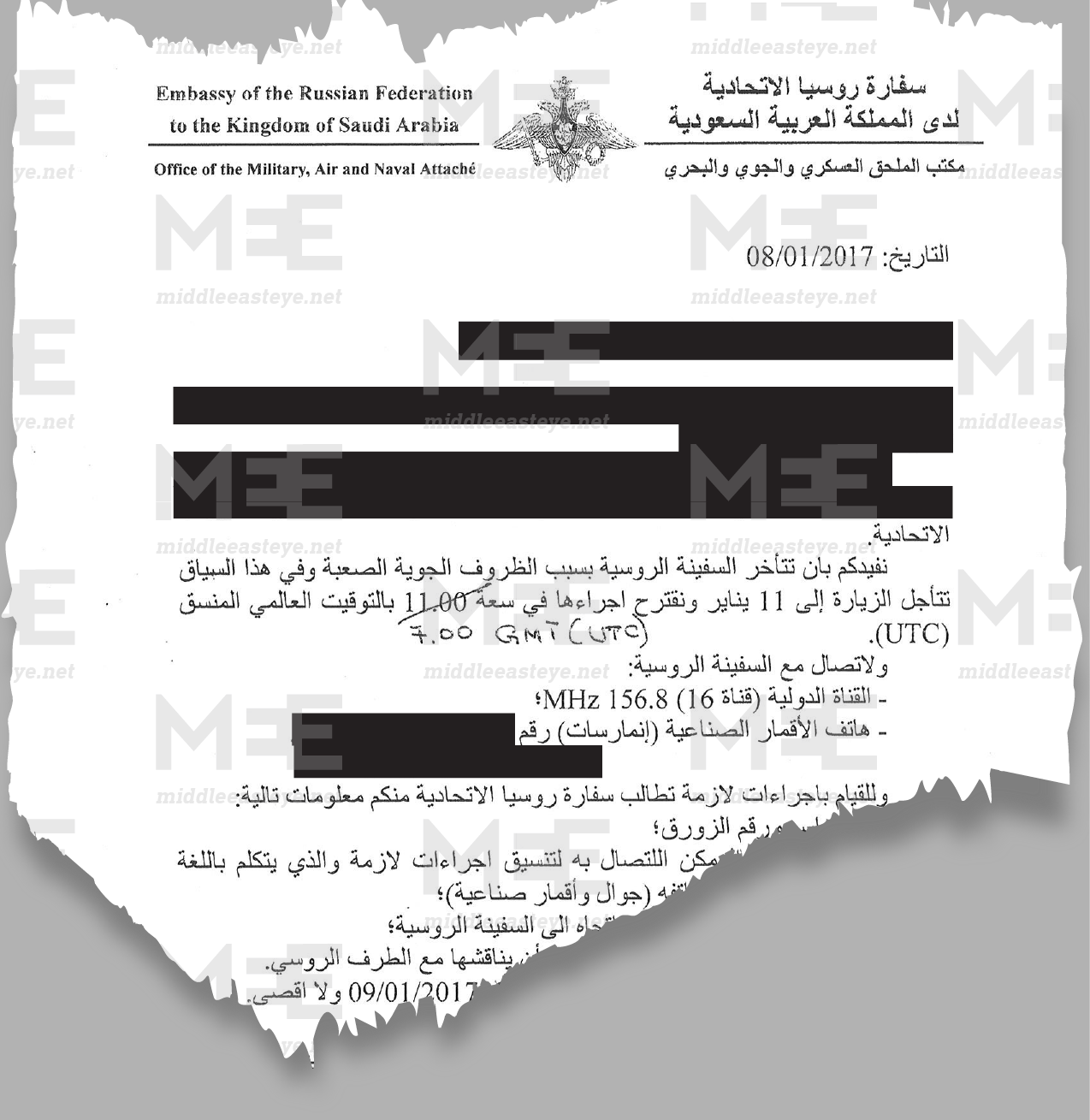

Three days after Haftar’s letter to Shogui, Kirichenko wrote to Libya’s then-ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Abdul-Basit al-Badri, warning him to keep plans for the aircraft carrier meeting secret and “within the framework of bilateral Libyan-Russian relations only”.

Badri was seen as a close ally of Haftar and travelled often to Moscow to meet senior Russian officials. Russia reportedly pushed for him to be named Libyan defence minister in 2015. Since 2021, he has served as ambassador to Jordan.

Badri told MEE that he severed ties with Haftar in 2017 and that he has had "no contact" with the Russians for years.

The Russian embassy said Haftar should arrive at the aircraft carrier by boat and provided a maritime satellite phone number for him to call. They also requested the contact person coordinating the trip on the Libyan side speak English or Russian.

Kirichenko wrote to Badri one day before the meeting was meant to take place, delaying it for two days to 11 January because of bad weather. He also requested the Libyans submit a list of topics to discuss.

Longstanding interest

In recent years, Russian interest in Libya has been viewed mostly through the activities of the Wagner Group, a shadowy private paramilitary that has gained notoriety in conflicts such as Ukraine and Syria and is led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a close associate of Vladimir Putin.

Wagner fighters, deployed with Moscow's consent in 2019, are believed to have been funded by the UAE, at least initially.

However, as the cables show, Russia's military had significant interest in Libya long before Wagner reached its shores.

“We all imagine Wagner was obsessed with Libya from the beginning, but it was the Russian state - Putin - who was obsessed. When the Russian state first saw Libya as strategically important, Wagner barely existed,” Jalel Harchaoui, a Libya expert at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, told MEE.

Before Muammar Gaddafi was toppled by a Nato-backed uprising in 2011, Putin's government inked $4bn worth of construction and arms deals with Libya - an investment that Russia has since sought to claw back through engagement with various rival Libyan parties, including Gadhafi's son, Saif al-Islam, and even the Tripoli-based government Haftar went to war with.

Yet Haftar, who remains in effective control of eastern Libya and has enjoyed significant backing from the UAE and Egypt as well as diplomatic cover from France, emerged as Russia's premier partner in the country.

Though Saudi Arabia has hosted Haftar and the liaisons between the commander and Russia were conducted on its soil, the Saudi government is not mentioned in the cables. Riyadh has, however, supported the commander by providing funds for his assault on Tripoli, reportedly including paying Wagner fighters and lobbying for him in Washington.

Russia is believed to have supplied Haftar with weapons, advisors and money.

Later, during Haftar's 2019-2020 war on Tripoli, which killed at least 2,500 and displaced another 150,000 people, Wagner fighters provided training, aided artillery units, provided security to high-ranking members of the LNA, repaired and serviced equipment, and operated Pantsir anti-aircraft systems. As the conflict progressed, they took an increasingly offensive role, laying landmines and booby traps and taking up sniper positions.

“For Libya to make sense from a business perspective for Wagner, you need to get to 2018, when the UAE ups funding for Haftar to attack Tripoli," Harchaoui said. "Then you have a market and if you are Prigozhin, there are all kinds of reasons to believe you will get the cash you need."

Today, some of the estimated 1,000 Wagner fighters deployed in Libya remain in the country's east and centre, though the group has expanded its operations elsewhere in Africa and played a leading role in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Its mercenaries have been sent to Mali, Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR), where they control lucrative gold and diamond mines. MEE has previously reported on massacres carried out by Wagner fighters around gold mines in the CAR.

Samuel Ramani, a fellow at the Royal United Service Institute and author of a new book on Russia in Africa, says Libya is a linchpin for Russia's ambitions in the continent.

“Libya is the Kremlin’s connection to the Sahel. Russia has always viewed Libya and Mali as an integrated theatre," he said.

“Libya has grown in importance to the Kremlin as it looks to project power in West Africa, following the Ukraine war."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].