Smile, General: Syrian drama breaks taboo with brutal portrayal of Assad-like family

For the past half-century, concrete taboos have governed the content of Arab TV, especially during Ramadan when viewership is at its highest. Religion and sex are heavily modulated, but most important of all is avoiding criticism of ruling families.

In fact, no fiction has been allowed to unfavourably approach ruling families in the Arab world. Even Nasser biopics, many several decades after his death, are coy in their denunciation, never questioning the Arab nationalist project that is partially responsible for the widespread autocracy in the region.

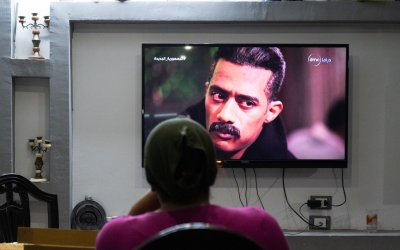

It was therefore a shock when this writer discovered Smile, General, a Syrian Ramadan TV series about a corrupt ruling family obviously closely modelled on the Assad family.

Known as Ebtasem Ayoha Al General in Arabic, the show is made entirely by a crew of dissident artists scattered across Turkey, Lebanon, and Paris. It was broadcast on the Qatar-based network Al Araby TV, and Syria TV, an independent anti-Assad leaning satellite channel based in Turkey.

Although initially broadcast with little fanfare the show had become the talk of the Arab world by the second day of Ramadan when word started to get around.

The series opener averaged 2.7 million views on YouTube and every subsequent episode averaged 1.7 million on the platform, with a totasal of more than 50 million views to date.

Smile, General is the most-watched Syrian series in recent memory by a long margin, and possibly the most-watched non-Egyptian series during Ramadan 2023.

The hype is understandable. Despite the declaration at the beginning of every episode that “all characters and events are fictional,” it was clear from the start that the Syrian-Arabic-speaking ruling family are stand-ins for the Assads.

President Furat (Maxim Khalil) is Bashar or Hafez; Assi (Ghatfan Ghanoom) is a blend of Maher and Rifaat Assad, Furat’s wife, Sophia (Rim Ali) is Asma Assad; Samia (Sawsan Arsheed), is his sister Bushra; the mother (Azza Al Bahra) is Hafez Assad’s widow, Anisa Makhlouf; Anis El Roumy (Mazen Alnatour) is Bashar’s cousin, Rami Makhlouf. Haider (Abdlhakeem Kutifan) is Bashar’s security adviser, Ali Mamlouk.

Rise to power

With these obvious parallels in mind, it’s difficult not to also find similarities between the unfolding drama and real life, especially since scriptwriter Samer Radwan infuses his story with events drawn from Syria’s modern history.

For anyone who sees Assad as a callous criminal responsible for the death and displacement of millions, the overall viewing experience is tantalising.

Smile, General has done the unthinkable: shattering the sanctity of an incumbent ruling family for the first time in Arab film and TV history.

Despite the dominance of the Saudi conglomerates and the staunch censorship across the region, it’s not far-fetched to believe that this polemic series could prove to be a turning point in the development of Arab TV production.

Episode one starts with a catchy premise; retired army general Waddah Fadlallah (Mohamad Al Ahmad) organises a party for the cream of the country's elite.

The cordial atmosphere of the opening minutes is ominously displaced as Fadlallah reveals that he has slept with every single woman at the party, including the president’s sister, Samia. He also exposes vast corruption amongst the ruling elite.

Fadlallah is prompted to come clean after a diagnosis of terminal cancer and subsequently goes into hiding, leaving the ruling family shaken to the core.

Furat and his brother, army chief Assi, radically disagree on how to deal with the situation, with the former demanding patience and measured action and the latter wanting a more radical and violent solution.

When a TV station in a neighbouring liberal country (a stand-in for Lebanon) reports on the party and broadcasts Fadallah’s allegations, Assi goes out of his way to have the head of the broadcaster assassinated, shattering the already frail relationship between the brothers.

What follows is a bloody power struggle involving Furat, Assi, the pair’s henchmen, the women of the family, and western governments.

Each episode opens with a quote from Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince, punctuating the drama with a philosophical undertone that positions the family's scheming in a grander context.

Furat’s ascendance to power is revealed in flashbacks. After his father’s death, he was chosen to replace the deceased president, but not before shooting a military general in the head who objected to the decision.

A change of constitution was needed to allow the inheritance of power in a manner that resembles the real-life constitutional amendments of 2000 that lowered the minimum age of presidency from 40 to 34, allowing Bashar al-Assad, who was 34 when his father died, to run for the presidency.

Like Bashar, Furat – young, insecure, and inexperienced – appears reluctant to take the throne, and only agrees when he accepts that assuming the presidency is necessary in order to safeguard his family and prevent retribution for his father’s depraved reign.

Assi, by contrast, is power-obsessed. Like Maher and Rifaat, he is a loose cannon: violent, merciless, and utterly reckless, determined to govern with an iron fist, and less shrewd than Furat.

The sister, Samia, emerges as the rebel of the family, like the real Bushra al-Assad, who was considered the most progressive member of the family and fled to the UAE amid the war.

Shortly after she got married, Samia's husband, who was never approved by Furat, disappeared and was believed to be dead. Later she discovers that he had been detained all along, propelling her to ignite a riot inside the family household.

'Isolated from reality'

Radwan injects his complex characterisation of Furat and Samia with some dignity, portraying them as the byproducts of a dog-eat-dog world that they had no choice but to be a part of.

Make no mistake though, this is an unflattering portrait of the Assads: a self-serving family whose sole raison d'etre is self-preservation.

Like Bashar, Furat is time and again shown as isolated from the reality of his country and his people.

In one surreal scene in the second half of the series, he hits the street and instantly gets mobbed by an adoring crowd when Assi tries to topple him. Furat feeds on this delusion, even though it’s clear that the mob has been organised by his aides for publicity.

Family dynamics aside, various other events in the series are clearly closely modelled on real incidents. Assi’s attempts to dethrone Furat, for example, recall that of Rifaat Assad against Hafez in 1984.

The assassination of the TV station owner is also similar to the 2005 murder of Lebanese-Palestinian journalist Samir Kassir – a strident opponent of Syria.

Later in the series, a secret detention centre built by businessman Anis becomes the sight of a massacre where accidental witnesses to the aforementioned plot are killed in cold blood and dumped – an incident recalling the Tadamon massacre in 2013 when 41 civilians were killed by members of the Syrian Armed Forces.

Other episodes are less explicit, touching upon broader mendacious Arab politics: from the rendition centres erected for the US to the use of Islamist groups as both scapegoats for state-sanctioned violence and as a manufactured opposition. There are also covert agreements with Israel used to consolidate the rulers’ authority.

As such, Smile, General is not just a disparaging portrait of the Assads: it’s an incisive dissection of an increasingly homogeneous region where the rights of individuals are nonchalantly bulldozered and shady pacts with foreign powers are necessary to maintain order.

While the show is primarily focused on the gory contest for power, in which all but Samia are implicated, the reality of Syria is underlined in the latter half of the story; a state replete with oppression, economic depression, and state terror.

Furat, time and time again orders the quashing of opposition; his entourage views civilian casualties as a perfectly acceptable part of maintaining their power.

A dissident work

Smile, General is made entirely by dissident Syrian artists, all of whom are known for their opposition to the Assad government.

Radwan is one of the divisive writers in Syrian drama, who sided with the Syrian revolution in 2011 before fleeing to Lebanon and later settling in Turkey.

His previous work was no less prickly. His TV trilogy El Welda Men Al Khassera (A Difficult Birth) was made in the wake of the revolution from 2011 to 2013 and discussed class disparity, poverty, police brutality, and Assad’s repressive policies.

His writings went by unpunished for a while but he was eventually accused of “undermining the authority of the state” and “conspiring for armed insurrection” and was consequently arrested in 2013.

Equally contentious was his 2019 series Dakekt Samt (A Moment of Silence) which highlighted the degraded state of the legal system and prison abuses.

Lead actor, Maxim Khalil, has also been in hot water in Syria. In 2013, at the Lebanese Murex D'or awards ceremony, Khalil gave a nod to the artists who have been detained by the Syrian authorities, including Radwan.

In 2014, he openly expressed support for the peaceful civilian demands to end Baathist rule.

After being blacklisted, Khalil and his wife, Arsheed, temporarily moved to Lebanon before settling down in Paris.

A number of pro-Assad Syrian celebrities have condemned Khalil and the series over the past month. In a televised interview last week, actor Yasser Yakhour criticised Khalil for taking on “such a controversial series,” asserting that he disagrees with both Khalil’s politics and the show.

“The series breaches all artistic logic,” he said, adding that: “Art should not be so direct in its goals.”

Director Mohammed Abdel-Aziz describes the show as “the worst Syrian TV drama in 10 years,” describing its writing in a radio interview as “weak, infantile, crude, and too ideologically direct,” further attacking sympathetic viewers for being “against the project of the Syrian state”.

Actor and director Aref Al-Taweel, meanwhile, admitted he hasn’t watched the show but is vehemently against it nonetheless. “I steer clear from any work of art with any targeted political messages,” he said.

But the objections by the show's detractors seem to have fallen on deaf ears. A flood of comments from Syrian viewers has invaded social media, with many in Syria eluding the censors by referring to it as “that show".

'Shallow characters'

The massive popularity of the show should not cloak its palpable inadequacies, however. At 30 episodes, the series is too long. It can be repetitive and this drags the rhythm of the story down, resulting in a weak middle that could have easily been condensed.

Many of the characters are also one-dimensional, including Furat and Assi who seemingly possess no inner lives and care about nothing except the throne. Assi in particular comes off as a cartoonish villain – a screaming gun-blazing maniac whose thirst for power is rooted in little brother syndrome.

By comparison, the women of the family, especially Sophia, are considerably more complex and more Machiavellian, happy to share power as long as they have a role in governance.

Saudi conglomerate MBC is not expected to pick up the show for its streaming service Shahid, while Netflix may deem it too controversial to acquire

Some of the politics are somewhat off. Assi’s allegiance with France to topple Furat is rootless and unjustifiable. The portrayal of the western media as little more than pawns that are fully controlled by their respective governments is implausible and jarring.

The role of the US and Russia, apart from their interest in the aforementioned rendition centres, is not entirely fathomable.

The direction of Orwa Mohammed, while generally competent and fluid, suffers from visual staidness on some occasions and excessive exuberance on others.

But these shortcomings take nothing away from the importance and brilliance of the series, which was made under unthinkable conditions, including the predictably severe scrutiny of the Assad government.

Entirely bankrolled by Qatari company Metafora – the independent production house behind Oscar-nominated The Man Who Sold His Skin, Palestinian Locarno contender Wajib, and Syrian Venice award-winner The Day I Lost My Shadow – Smile, General did not have the advantage of state-backed TV or massive broadcasting deals like its competitors.

Saudi conglomerate MBC is not expected to pick up the show for its streaming service Shahid, while Netflix may deem it too controversial to acquire, particularly for the lucrative Saudi market.

As Saudi Arabia pushes for normalisation with Syria, Smile, General emerges as a reminder not only of the brutality of the House of Assad but also of the crimes the Arab League is now willing to turn a blind eye to.

Nevertheless, the success of the show should embolden dissident artists from disparate parts of the region and encourage them to follow suit.

A grand revolution in Arab TV is not expected anytime soon, but the show has certainly succeeded in stirring the politically still water of the region’s TV industry.

For now, it’s sufficient to celebrate Smile, General for what it is: a large thorn in the side of a regime that might realise now that the road to legitimacy may not be as smooth as it presumed.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].