Turkey elections: Has the country reached an economic breaking point?

There are two types of countries in Turkey's neighbourhood: ones where you know the election results before voting starts, and ones where you don't. Turkey is still in the second group.

Turks are proud of their decades of experience with the ballot box. We know that it can work wonders; the voting booth is perhaps the only place where we feel totally free. Elections are the primary direct link between politicians and citizens in this country.

With Turkey's presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for Sunday, we still don't know for certain who will win - and that's a good thing. There seems to be some change in the air, but Sunday will tell us precisely how much.

A number of issues will factor into the outcome. Firstly, Turkey is in the midst of an economic crisis. Compared with the 2001 financial crash, banks and companies are in better shape today. Public debt is around 27 percent of GDP, ample fiscal room to finance the cost of earthquake with debt. Note that the EU limit for the share of public debt in GDP is 60 percent.

Secondly, there has been a rapid rise in the rate of inflation, which is now around 50 percent. The country is in a severe cost-of-living crisis, felt most acutely in large metropolitan areas. Usually, public sector employees such as doctors, nurses, police and soldiers angle for appointments in larger provinces; in today's economy, appointments in smaller towns are preferable.

In terms of public services, the quality is declining most rapidly in places where the per-square-metre cost of real estate is highest - not only in Istanbul, but also in places such as Bodrum and Antalya.

According to calculations by our team at the Economic Policy Research Foundation of Turkey, the cost of living in Istanbul is 40 percent higher than the national average. But this relies on data from the Turkish Statistical Institute (Turkstat), which is not always reliable; the real figure is likely much higher.

Unsustainable situation

Thirdly, the poverty incidence, defined as the share of the population living on less than $5.50 a day, is on the rise. It was around 37 percent when Recep Tayyip Erdogan became prime minister in 2003. Through the inclusive growth policies of his early years, that figure had declined to eight percent by 2018, but two years later, as the Covid-19 pandemic hit, it was back up to 12 percent.

After 2020, Turkstat stopped doing household surveys, making calculations of precise poverty incidence impossible. The World Bank estimate for poverty incidence today is around 25 percent, suggesting a 100 percent increase in only a few years.

The late Suleyman Demirel, Turkey's former president and veteran of many elections, used to say: "There is no government an empty pot cannot topple." To return to the issue of the upcoming election, will it be good for the Turkish economy? The answer is yes, because the current economic situation is totally unsustainable.

Since 2018, when Turkey ushered in a super-presidential system, Erdoganomics has been all about tactics, and no strategy. This system bypasses any form of real expertise, but the motivation is unclear, as it is obviously not working. The country has lost its capacity to make policy - and not just in the economic sphere, but also in education, foreign affairs and other areas.

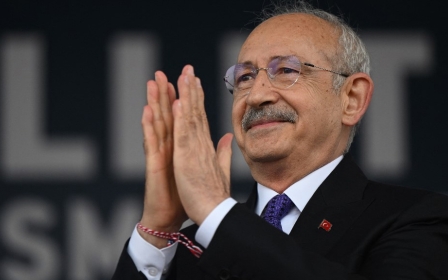

Everyone is now wondering what will happen the day after the elections. Suffering from a massive credibility gap, a victorious Erdogan would not be able to lead Turkey towards a rapid economic recovery. On the other hand, the leader of the opposition alliance, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, has a highly visible and experienced team that could quickly stabilise the economy. Having prepared a 240-page and 2,300-issue long joint policy memorandum, Kılıcdaroglu's six-party economic policy team of academics and former bureaucrats have been working together over a year now.

But the question remains: can stabilisation be achieved without intervention from the International Monetary Fund (IMF)? In the case of an Erdogan win, the IMF would become absolutely necessary; in the case of a Kilicdaroglu victory, it wouldn't be needed at all. It's all about the credibility gap, very high for Erdogan due to his infamous track record of "interest rate is the reason and inflation is the result", and none at all at the moment for Kilicdaroglu, who would start the job with a clean slate anyway.

Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu once said that "tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat". I'm afraid that's where we are now headed - and it is already too late for Erdogan to correct course. The former central bank chief, Naci Agbal, might have been his last chance, but Erdogan insisted on sacking him in 2021. That might have been the beginning of the end for the Turkish leader.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].