Sands shift in Western Sahara’s aid-gate scandal

With the stalemate of the Western Sahara dispute now entering its fifth decade and seemingly no nearer resolution, it is hardly surprising that many people have difficulty in fathoming out just what is going on.

By the end of 1975, the waning Franco regime had attempted clumsily to extricate itself from its colonial responsibilities in the region; Morocco had undertaken its now heavily mythologized “Green March” and the Sahrawi refugee camps in Algeria’s Tindouf region were in the process of establishment. More importantly, the International Court of Justice had determined that the indigenous population, the Sahrawis, were the owners of the land and therefore possessed the right of self-determination.

By that time, I had completed just over 10 years of study and a PhD on the Tuareg of the Algerian Sahara, but had carefully avoided any direct involvement in the unfolding Western Sahara dispute. Even then, any claim to expertise on the region looked like being a ticket for the “long haul”. And so it has proved.

At that time, there were no doubts about the rights and wrongs of the dispute: Morocco’s acquisition of the Western Sahara was “illegal” and for those who dreamt or fought for an independent Africa, the rights of the Algerian-backed Polisario (Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro), the UN-recognised representative of the Sahrawi people of Western Sahara, were clear cut.

Until recently, that has not changed. Moreover, Algeria has been able to hold on to the moral high ground, in spite of its human rights abuses of both its own citizens and the Sahrawis in the Tindouf camps and the growing evidence of the Polisario’s involvement alongside Algeria’s secret service, the Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité (DRS), in terrorism, drug trafficking and other such criminalities.

But not any more. In early-February 2015, Algeria lost its credibility in regard to the Western Sahara dispute. The reason was the publication of the European Anti-Fraud Office’s (OLAF) report into the decades-long embezzlement by the Algerian and Polisario authorities of humanitarian aid destined for the Sahrawi refugees living in the Polisario-controlled Tindouf camps.

OLAF’s report, based on the results of a survey that began in 2003 and was drafted in 2007, but not released publically until 2015, reveals that Algeria had been embezzling for decades much of the aid that was destined for the Tindouf camps, to the detriment of the Sahrawi refugees.

According to OLAF, the embezzlement was centred on the Algerian port of Oran where a large part of the aid was diverted away from its Tindouf destination. Good quality foods and medicines destined for the camps were replaced by lower quality goods by the embezzlers who resold them in Algeria or neighbouring countries.

Three obvious questions are why the EU did not publish the report when it was drafted, why it was published this year, and why the EU’s oversight and accountability was so lax.

EU 'destroyed report on aid fraud'

The EU has so far remained silent on the first two questions, although it is generally surmised that the report was not published earlier as the EU did not want to embarrass Algeria. Indeed, I have concrete evidence of the EU destroying another report in 2010 that was equally condemning of similar Algerian practices. There is speculation that the decision to publish the report now may have had something to do with the rebuff given to a high-level EU parliamentary delegation visiting Algeria in November 2014.

Amar Saadani, the secretary-general of Algeria’s National Liberation Front (FLN), tried to stop the delegation meeting political leaders of political parties other than the ruling FLN. A former senior EU official, with whom I discussed Saadani’s behaviour, confirmed that “the EU had finally had enough” of Algeria.

The EU has made no comment on the third question, although its lack of oversight makes it unlikely that it can or will demand reimbursement. However, following the revelations of the OLAF report, the EU decided to drastically reduce its €10 million annual allocation to the Tindouf camps.

The fraud had long been suspected by Morocco. But because of Morocco’s own involvement in the dispute, little credibility was given to such claims: Morocco would say that, wouldn’t it?

However, for those who have stood for so long behind the Algerian-Polisario position, news of the fraud has come as an immense shock. The question now is what the consequences of this revelation will be for the overall Western Saharan situation.

Polisario tarnished

The first and most obvious consequence is that it has destroyed much of Algeria’s credibility and shifted the moral high ground away from Algeria. The Polisario leadership’s complicity in the fraud has left its reputation equally tarnished. Speaking in Geneva on 3 February, Jean-Marc Maillard, the Swiss regional expert on the MENA region, deplored that the embezzlement had been perpetrated “in full connivance between the Algerian regime and its Polisario henchmen”.

There are also indications that more members of the European Parliament (MEPs) are now expressing support for Morocco’s “autonomy” proposals for the Western Sahara dispute. Indeed, MEPs anger at Algeria’s fraudulent practices appear to have been reflected in the European Parliament’s approval and adoption on 12 March of a new report on global human rights and democracy, by 390 votes to 151 with 97 abstentions, which hailed Morocco’s efforts in promoting human rights and rejected amendments introduced by Morocco’s opponents, namely Algeria, to extend the mandate of the UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO) to include human rights monitoring mechanisms.

But the main consequence of the fraud is that Algeria and the Polisario will no longer be able to maintain the status quo by refusing to allow a UN census of the refugee population in the camps, as they have done for 39 years. The world now knows that the reason why Algeria and the Polisario have refused to facilitate a census is because it would have put an end to their lucrative fraud. Since 1975, the EU’s aid to the Tindouf camps has been based on the Algerian authorities’ estimates of a refugee population of 155,000-165,000, although OLAF unilaterally lowered that estimate in 2005 to 90,000, a figure thought to be nearer the real number.

What is striking about this year’s annual report of UN Secretary-General (UNSG) Ban Ki-moon, released on 10 April, is that it made no mention of the substantiated embezzlement of humanitarian aid by the Polisario and Algeria. But that is because Ban Ki-moon is the consummate diplomat and had bigger fish to fry.

Veiled threat from UN

His report, adopted by the UNSC, not only rejected the call made by the African Union, at Algeria’s instigation, to expand the MINURSO mandate to include human rights monitoring in the Moroccan Sahara and Tindouf camps, but also insisted that a census be undertaken of the population held in the Tindouf camps. The veiled threat, should Algeria continue to block such a census, is to raise the matter of the embezzlement at the level of the UN Security Council - the ultimate international humiliation for Algeria.

Thus, although the UNSC’s renewal of the MINURSO mandate for another year (until 30 April 2016) may, on face value, not look momentous, it is being trumpeted by Morocco and its supporters as a great victory. That may be premature. But if Morocco’s ebullience transpires to be justified, it will not be because of any grand moves by Morocco, but rather because of Algeria’s default. Algeria has shot itself in the foot.

In the same way that history may come to explain the collapse of Algeria’s Bouteflika regime in terms of its endemic corruption, so the demise of the Algerian-Polisario position - if that is what we are about to see - may ultimately come to be attributed to nothing more than another case of “fingers in the till”.

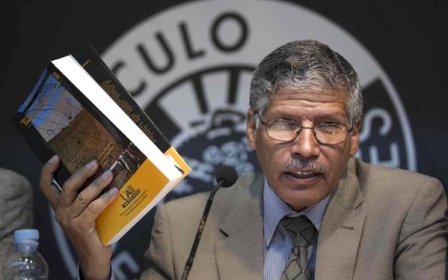

- Jeremy Keenan is a Professorial Research Associate at the School of Oriental and Africa Studies. He has written many books including The Dark Sahara (2009) and The Dying Sahara (2012). He acts as consultant on the Sahara and the Sahel to numerous international organisations, including the United Nations, the European Commission and many others.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Sahrawi woman walks in the desert on March 1, 2011 near the Western Sahara refugees camp called '27 February' in Tindouf. Western Sahara is a former Spanish colony which was annexed in 1975 by Morocco. (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].