Western Sahara's prime minister in the desert

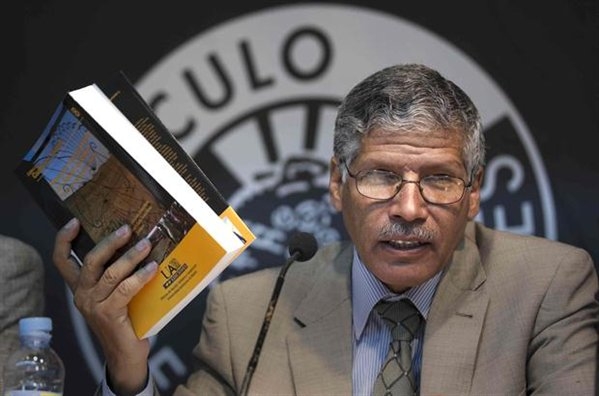

TINDOUF, Algeria – Abdelkader Taleb Omar is the head of a highly unusual government. As prime minister of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) he is, in effect, the prime minister of a refugee camp.

The SADR is the government in exile of Western Sahara, a huge territory in North West Africa that has been effectively occupied by Morocco for almost 40 years.

Its operations are based in Rabuni, the administrative centre of a group of refugee camps in the Algerian sahara where – since the Moroccan invasion of the territory in 1975 – a substantial percentage of the indigenous population of Western Sahara live.

I met Abdelkader in a small, semi-official, almost deserted building on the edge of the most remote of the Sahrawi refugee camps. The building itself was little more than two rows of white, square rooms separated by an open air corridor and he had installed himself in the first room on the right for our interview.

In his twenties Abdelkader had fled the Moroccan invasion along with almost half of his people and had climbed his way up the political ranks, serving as speaker of the Sahrawi parliament, then governor of one of the refugee camps, before being appointed prime minister in 2003. He was diffident, uncharismatic, and cautious, but I suspect more out of general fatigue than fear of misspeaking.

As head of the government in exile, he is faced with a number of challenges. He must govern the refugee camps themselves, oversee the representation of the Sahrawi cause internationally, and ultimately work to achieve self-determination for the Sahrawi people.

Day to day, however, he has a bigger problem: convincing the refugee population of the need to maintain peace with Morocco, the nation occupying his country.

For 15 years the organisation that formed the SADR – the Sahrawi independence movement known as the Polisario Front – fought a guerilla war against Moroccan forces for control of Western Sahara.

The Polisario was originally formed to fight the Spanish colonial administration of the territory in 1973, but after the Spanish withdrew and Morocco and Mauritania invaded it shifted its efforts to fighting them. The Polisario saw off Mauritanian forces quickly, but was unable to do the same with Morocco and the latter annexed Western Sahara.

A ceasefire was signed by the Polisario and Morocco in 1991.

“The fact is there were many victories during the 15 years of armed struggle but if we are honest peace has brought stagnation,” Abdelkader said. “And one of our main problems now is how to get the people to keep on accepting the peace process.”

In 1991 the Sahrawi were promised a UN-organised referendum in which they would determine the fate of Western Sahara, one that both Morocco and the Sahrawi predicted would end in independence. However the referendum has still not been held and many have lost hope in peace.

“Some of the youth only want armed struggle at this point. They know that at the beginning of the war we captured many soldiers, weapons, tanks, and we were fighting for our land,” Abdelkader said.

“The desire to fight in the face of injustice is a human reaction.”

However the SADR's current policy is to support a peaceful negotiated international settlement through the UN.

The SADR and Polisario leadership have often hinted at returning to armed struggle with Morocco but little has ever come of it.

When asked whether he thought the Sahrawi could realistically win a war with Morocco, the prime minister said he believed they could, but it is difficult to see how - and the leadership's policy of supporting peace probably reflects this reality.

“There is very low trust in the UN here in the refugee camps given what has happened since 1991, but we are still optimistic that Morocco will one day accept a referendum, one way or another,” Abdelkader says.

“History has taught us that the liberation fronts always win in the long term.”

The Moroccan government argues that its right to Western Sahara, which it calls Morocco's “southern provinces,” is derived from its pre-European colonial empire.

Abdelkader answers that Morocco has no more right to Western Sahara than it does to Andalusia, which was also once part of that empire, and international law has been on his side since the World Court reached essentially the same conclusion in 1975.

However recently there have been diplomatic setbacks for the Sahrawi. The April vote on extending the mandate of The UN Mission in Western Sahara (MINURSO), failed yet again to include the long sought-after goal of a human rights monitoring mechanism.

As a result, the prime minister says the SADR is analysing its strategic position, but he also pointed to the African Union's support for the Sahrawi cause as a triumph.

“The Moroccan regime is suffering because of its occupation,” he says. “In fact Western Sahara has become like a cancer for Morocco.”

“It has kept Morocco out of the African Union, and it is hindering the construction of the Maghreb Union.”

Khadija Hamdi, Abdelkader's minister of culture, a key SADR leadership figure, and also the wife of the current Sahrawi president in exile, thinks the Sahrawi need to change their approach.

“The conflict has persisted unresolved for 40 years and yes, there is a need for new thinking,” she told MEE. “We must review the mechanisms that we have in place politically.”

Like the rest of the Sahrawi leadership, she stresses the importance of international recognition and support but is unclear on where the new thinking should come from.

Abdelkader's foreign minister, an articulate man by the name of Mohamed Salem Ould Salek, who speaks four languages, said much the same.

He recognised support for Morocco in the UN Security Council from France and the United States as perhaps the most significant obstacle to a settlement of the conflict.

“The British government must this raise at the EU and show that France's position is unacceptable,” he said.

“The question must be asked, why has the EU not pushed Morocco? France must change its position.”

The Sahrawi leadership are clearly struggling with the incredibly difficult task of fighting for their legal rights in a world where connections and powerful allies are often more important than law or justice.

The comforts of feeling on the right side of history can't last forever but Prime Minister Abdelkader says the Sahrawi cause is one that is worth hanging on for.

Nonetheless in him and in other Sahrawi leaders one can sense a hint of weariness; they have been waiting in heat and squalor for decades.

“It is very difficult to keep hope,” he concedes, “However we are a small people who fought two occupiers [Morocco and Mauritania] and we drove one out.”

“In the end people will always prefer to fight for their freedom despite how hard life is here in the camps.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].