Egypt's Sisi is not Mubarak

Critics of Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi have frequently portrayed him as a reincarnation of his deposed predecessor Hosni Mubarak. They’ve labelled his presidency a more villainous, autocratic continuation of Mubarak’s, and on the face of it, this is easy to do: they are both retired military officers who went on to become infamous dictators. But that’s about all they have in common. Their political journeys, domestic and foreign policies, advisers and styles of governance could not be more different. Sisi is not Mubarak. It’s time we all acknowledged that.

To begin with, Sisi and Mubarak had drastically different journeys to the presidency. Mubarak’s political career began in 1975, a full six years before he would go on to become Egypt’s president.

During his years as vice president under Anwar Sadat, Mubarak became fully folded into Egypt’s political establishment. On his many diplomatic voyages, he developed strong personal relationships with important Arab leaders, including Crown Prince Fahd of Saudi Arabia and Sultan Qaboos of Oman. As deputy chairman of the ruling National Democratic Party (NDP), he was often called upon to fill in for Sadat when he was away and became a well-regarded party leader well before he assumed the presidency. And of course, as a decorated war hero and former deputy minister of defence, he enjoyed the loyalty of the armed forces as well.

When Sadat was assassinated in 1981, Mubarak glided more-or-less effortlessly into the presidency with the full support of Egypt’s Western allies, business elites, armed forces and the NDP.

Over the course of the decades that followed, Mubarak’s position in the political establishment only grew more concrete. He continued Sadat’s policies of privatisation to his great advantage: He sold off public companies to important political allies and gave the not-insignificant leftovers to the armed forces. And perhaps most significantly, he turned the NDP into Egypt’s primary political institution; would-be politicians at every level of government needed the endorsement of the NDP to secure an office.

Sisi on the other hand, is brand new on Egypt’s political scene. Before Mohamed Morsi appointed him as minister of defence in 2012, Sisi was virtually unheard of. Unlike Mubarak, he had an abrupt, unconventional and rocky rise to power. Less than a year after his appointment to defence minister, Sisi deposed Morsi in a popularly backed military coup. Then, a month and a half after that, he ordered the bloody dispersal of two massive Islamist protests. Over 1,000 people were killed and Sisi faced a strong wave of international condemnation. The US suspended its annual military aid to Egypt for the first time in over 30 years. Acting Vice President Mohammed el Baradei resigned in protest; and all around the country, supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood expressed their outrage.

When Sisi ran for president the following spring, he did so without the support of any political institution. In fact, the political scene was in such a state of chaos at this point that he barely even managed to find an opponent to run against him. Former establishment politicians from the Mubarak-era had been barred from running for elected office and the largest opposition movement, the Muslim Brotherhood, had been declared a terrorist organisation. He won virtually unopposed in an election with a 37 percent voter turnout.

Sisi has been afforded few of the luxuries Mubarak had. He has no more public companies to privatise and trade for political loyalty. With Egypt’s economy in shambles from the years of political instability, his relationship with business tycoons is precarious. And above all, he has no NDP, no political institution to give him legitimacy.

The only establishment providing Sisi with institutional backing is the Egyptian military. This is the main reason that Sisi is not Mubarak and never can be. It’s a significant point for two reasons.

First of all, this means that Sisi’s position as president is far from secure. Mubarak had a solid foundation upon which to build his political empire. Sisi stands on shifting sands with only the military to lean on. He has managed thus far to remain in the armed forces' good graces by supplying their companies with a steady stream of contracts for projects such as the New Suez Canal and the agricultural land reclamation project.

But funding for these projects and future projects is largely dependent on Gulf state investments - and with oil prices at decade lows, Gulf state finances are looking ever more precarious. If the money dries up, Sisi could find himself facing pressure not only from his people, but from a disgruntled private sector, not to mention his military officers.

In such a case, the armed forces might not object to another popular uprising to replace Sisi. Sisi knows this. His office is only secure as long his generals are happy - so he is fully committed to ensuring that they are.

Second of all, because Sisi is utterly beholden to the armed forces, this allows them to be more directly involved in politics than ever before in Egypt’s modern history. While Mubarak had a long military background, he was every bit a politician by the time he became president. Of course, he understood the value of maintaining the armed forces’ loyalty, but he never let them stray too far into the domain of governance. Sisi on the other hand served in the armed forces right up until he announced his candidacy for president.

While he may be a civilian on paper, he remains every bit the military’s man. Through Sisi, the armed forces have been able to dictate laws that give them expanded powers over the civilian criminal justice system and allow them to grow their share of the civilian economy.

Of the 263 decrees Sisi made in the absence of a parliament, 32 of them pertained to the security forces. He increased military pensions on multiple occasions, gave the military jurisdiction to secure all public institutions (including schools) and made amendments to laws governing the rank of military officers and their benefits.

Mubarak was a dictator’s dictator. He maintained the loyalty of key institutions across the ruling class without promising his loyalty to any. He was accountable to no one, beholden to no one. He ruled Egypt with impunity for 30 years. Sisi, however, is the military’s dictator. His allegiance is to the armed forces first; he acts on their behalf. As president, he is ushering in an unprecedented era of military rule in Egypt - and he’s only just begun.

-Emily Crane Linn is a freelance journalist based in Cairo reporting on social justice issues in post-revolution Egypt. She is currently conducting research on a narrative non-fiction book project.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

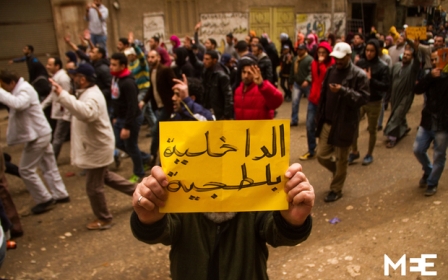

Photo: An Egyptian holds a poster featuring toppled president Hosni Mubarak and then general but now President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi on 14 September, 2013 in Cairo (AFP).

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].