The Palestinian who captured the vanished world of old Bethlehem

The address Number 1 Nativity Square in Bethlehem no longer exists, or rather, pilgrims and tourists assume it must be the address for the city’s number one tourist destination: the Church of the Nativity. In traditional Christian belief, the church is built over the original birthplace of Jesus Christ and is said to be the oldest church in the world.

Nativity Square, where the church still stands, used to be lined with businesses and homes before they were demolished in 1962 by the Jordanian government to make room for a bus station. None of the original Nativity Square addresses survive.

Recently, Bethlehem native George al-Ama uncovered the address in his pursuit of finding Bethlehem’s first local Palestinian photographer, Zakariah Abu Fheleh. Al-Ama is a collector and researcher who specialises in the cultural history of Palestine. When he begins speaking about Abu Fheleh, a confident, determined tone of an art sleuth comes to the fore.

“I inherited a treasure,” al-Ama said, surrounded by contemporary Palestinian paintings in a Ramallah art gallery, a place where he seems most comfortable. “I inherited the photographs of my great grandfather, Jacob al-Ama, who died in 1933, through my uncle in Germany. Immediately I started looking through the box and I recognised many names like Khalil Raad, Garabed Krikorian. These were photographers who were working in Palestine in the 19th century, early 20th century - some highly important studios.”

Al-Ama knew that he had come across valuable objects when he saw the names of Raad and Krikorian, as they were known to have had successful, though competing, photography studios in Jerusalem at the turn of the 20th century. To his surprise, in the box was another familiar name, one that al-Ama did not expect to see at all.

“Later I came across the name Zakariah Abu Fheleh,” al-Ama said. “I immediately recognised the name of the family because as a collector of mother of pearl handicrafts, I know the name Jacob Abu Fheleh, which I was looking out for nearly daily. Any signed piece is extremely rare.”

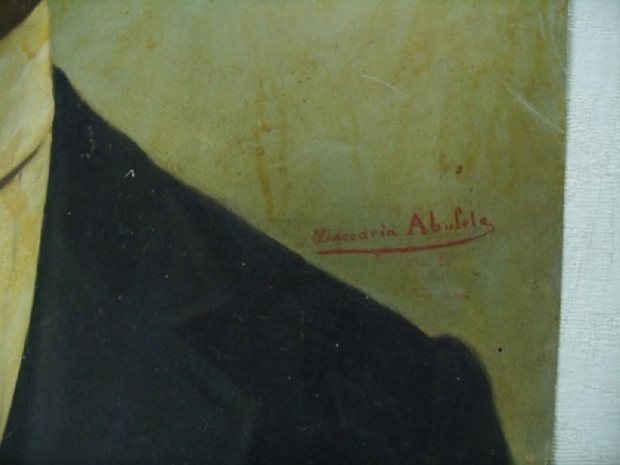

Al-Ama was familiar with the valuable mother of pearl crafts by Jacob Abu Fheleh and knew that there must have been a connection between the two artisans. He soon discovered that Jacob Abu Fheleh was the uncle of Zakariah, who was born in 1885, and the two would go on to share Number 1 Nativity Square as their place of business.

Piecing together the photographic puzzle

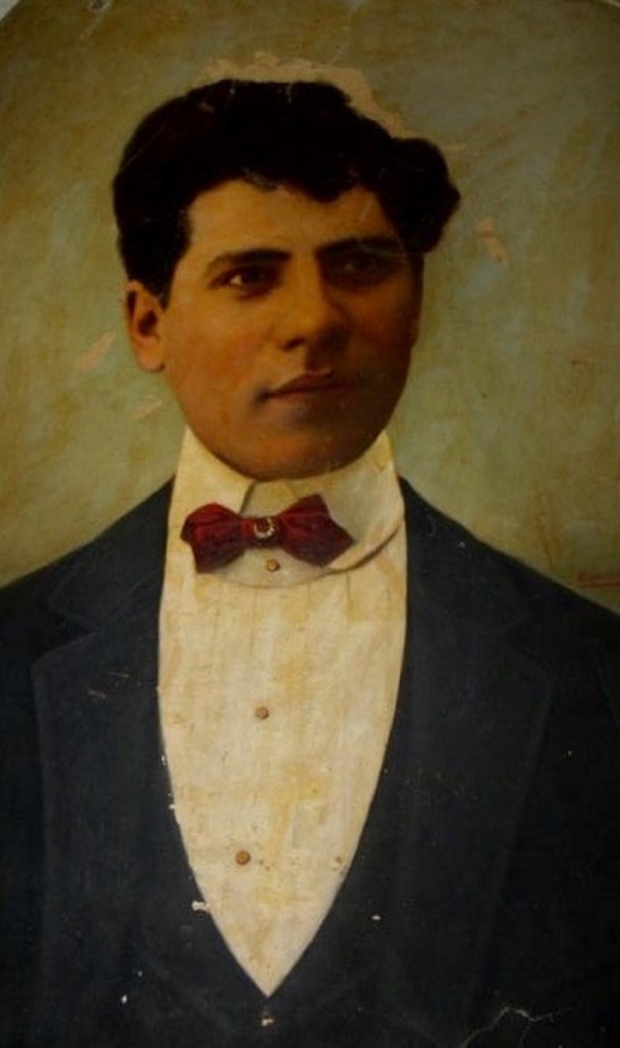

Al-Ama began using paintings and photographs from his and other Bethlehem collections to pinpoint the establishment of the studio in 1907. Before this, any studio photographs of Bethlehemite families he found had been taken in Jerusalem by Krikorian, an Armenian, or Raad, who was Lebanese.

“If we had a photo studio in Bethlehem in 1906, we would never go to Jerusalem,” al-Ama said, sitting up straight and taking on a tone filled with pride. “We have this notion that if there’s a Bethlehemite who is working in a specific field, we wouldn’t go anywhere else. By studying surviving photos as examples, I’ve managed to discover the exact date of the establishment of the studio and to link the style of Abu Fheleh to Khalil Raad, and later to claim Zakariah Abu Fheleh as the first pure Palestinian photographer.”

He then located other large, overpainted photographs by Abu Fheleh and believes that he and Raad - who offered large photographic enlargements from his studio - were working together to create them.

At this point in his life, Abu Fheleh was only 21 years old. Al-Ama sees this partnership as the beginning of Abu Fheleh’s career as both a talented artist and photographer. In 1907, just one year after the completion of this overpainted portrait, black and white photographs of Bethlehemites with Abu Fheleh’s studio signature began to appear.

“I think that Abu Fheleh was that clever to take photography into the Bethlehem society,” al- Ama said.

“He opened a studio because there was a big need for a photography studio in the area and he was in the centre of the centre. It was that easy for him to take a photo for a wedding in front of the door of the Nativity because he was only 35 metres away from the door. To take the heavy machinery and the heavy tripod and the cloak and all of those elements and components – it was that easy.”

Rewriting Palestine’s photography history

Knowledge of Abu Fheleh’s photography studio has reached beyond Bethlehem’s confines and is now helping to solidify a Palestinian presence in early photographic history. Dr Salim Tamari is a senior fellow at the Institute for Palestine Studies and the editor of the Jerusalem Quarterly Journal.

Tamari's office in Ramallah is lined with photography books in both Arabic and English, clearly demonstrating his passion for the medium. Every mention of an early photographer leads to a story about another studio, another collector, or another little-known archive. Tamari recently co-sponsored al-Ama’s introductory talk on his discovery.

“Most visual images of the Middle East come through pilgrims, Orientalists, and visiting photographers who, in the tradition of David Roberts and the early photographers, created an image of the exotic East,” Tamari said. “We’re trying to see how native photographers of all ethnic and religious groups saw Palestine and the East from their own perspective.”

Khalil Shokeh, a native Bethlehemite and local history scholar, agrees. He has worked with al-Ama on many projects and exhibitions using early Palestinian photography as his muse.

Shokeh’s intricate knowledge of his home city stretches from the early Ottoman period to the present day, but he is especially excited by early photography, rapidly listing the reasons it needs to be seen and discussed.

“In the preface to my book, I said that photographs about Bethlehem and its citizens are documents of valuable history for unprecedented times,” Shokeh explained.

“I was talking about the attitudes of Western photographers at that time and when I reviewed the literature of those who wrote about the history of photography, their attitudes were full of prejudice and unfairness. To them, we were wild beasts, barbaric, uncivilised, and the pictures show this.

"So when you study more thoroughly about the Western photographers themselves, who sent them and why they were sent here, you start realising there was a name behind it, a goal behind it, politically, and religiously, and so on. They never understood that East is East and that it is simply different from the West,” he added.

For Shokeh and Tamari, al-Ama’s work uncovering Zakariah Abu Fheleh represents something greater than the discovery of an unknown photographer and artist. For them, it is something that contributes to all of Palestinian society.

“George is doing magnificent work that nobody else is doing,” Tamari said. “He’s going to families and asking. We do this with diaries, letters and papers, but he’s doing it with photography. He goes to local photographers - almost all of them are dead and he tries to trace their work through their families. It is magnificent work which has recorded a frozen time that’s completely disappeared.”

Having established the existence of Abu Fheleh’s studio, al-Ama is continuing his research by knocking on doors throughout Bethlehem, desperately trying to engage local citizens in his search for photographs that can tell history from a local perspective. What is especially frustrating for him is the amount of Bethlehem’s history dotted around the world as a result of emigration from Palestine, better known as the Palestinian diaspora.

“I felt upset that as a Bethlehemite we had such a pioneer in photography and all over Palestine and maybe in the Middle East nobody was writing about him, nobody knew him, nobody researched him,” al-Ama said.

“Even the people of Bethlehem know nothing about him, since he emigrated in 1917, 1918. Everything was lost, and he died in Colombia,” he added. Al-Ama took the same route out of Palestine as many Christian Bethlehem families who emigrated during World War I, according to historians. All of Abu Fheleh's family had left the city by the early 1920s.

This makes the historical discoveries by al-Ama all the more significant. “Every photograph for Palestine pre-Nakba and Naksa is important," he says. "It’s a record of buildings, of people, of costumes, of handicraft. Photography in Palestine, taken by foreigners or locals, is highly important, it is the best evidence."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].