Giant mural brings sunlight to Cairo's garbage district

"He painted a little fragment of the art on each building and the picture all comes together when viewed from one spot on top of the mountain - which you can see if you stand right by the church,” 16-year-old Simone Rateb said as she pointed to Saint Simon - or Samaan in Arabic - the monastery on top of the Moqattam mountain which faces her house.

She was talking about French-Tunisian artist eL Seed’s latest calligraffiti project - an art form that merges calligraphy and graffiti - in the working-class area of Manshiyet Naser in Cairo. The district, largely inhabited by Coptic Christians, has been built around a monastery that takes the shape of a cave inside Moqattam Mountain in Southeastern Cairo.

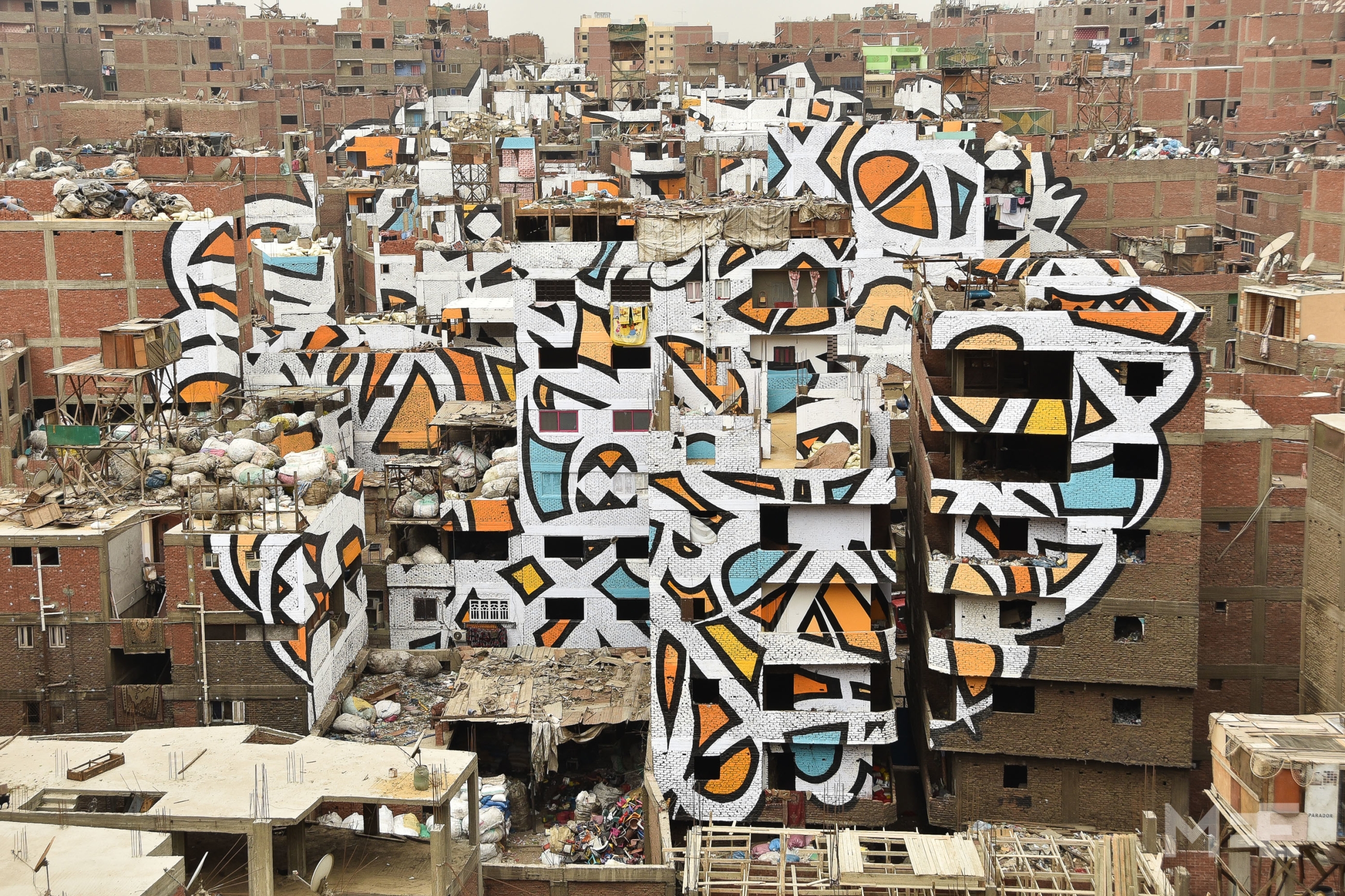

When standing on top of the Coptic Saint Bishoy’s pigeon tower, one can see bright abstract segments of orange, yellow, white, and blue painted onto the red-brick buildings of the Zaraeeb neighbourhood located in Manshiyet Naser.

The mural spans over 50 buildings, yet in between one can see balconies and bags filled with neatly separated waste that includes plastic, aluminum cans and more. On the rooftops, there are pigs, goats and other animals.

The residents were involved in the project “in every sense,” el Seed told MEE. “Part of my team were from the area. But everyone there was so welcoming of the project. They opened their hearts and their houses to us.”

From the monastery, the painted buildings appear in full circle and quote the words of the fourth-century Coptic Bishop Saint Athanasius: “Anyone who wants to see the sunlight clearly needs to wipe his eye first.”

Judgement and misconception

The garbage collecting residents of the impoverished community of Zaraeeb are often referred to as the Zabaleen, a word that means garbage collectors in colloquial Egyptian Arabic, and holds societal stigma. Through his endeavour, eL Seed contests this term.

The artist wrote a mission statement about his project, which he named Perception, saying that through it he questions “the level of judgement and misconception society can unconsciously have upon a community based on their differences.”

El Seed told Middle East Eye that Zaraeeb “was the ideal area to raise the topic of perception. It was a pretext to open a dialogue on the subject.”

“If the Zaraeeb community were in Japan or Peru, I would have gone there. They are seen as poor, marginalised, isolated. Actually they are the opposite of this. They are associated to those ideas because they work in the garbage. The most important thing about this community is that they don’t live in the garbage, but from the garbage. They are proud and strong people,” el Seed said.

“They have been given the name of Zabaleen (the garbage people), but this is not what they call themselves... they are the one who clean the city of Cairo,” eL Seed wrote in his project’s mission statement.

According to Bishoy Rateb, a resident of the neighbourhood, eL Seed and his friends continuously worked on the buildings for one month. He told Middle East Eye that people accepted eL Seed’s work because he got approval from the local priest, Father Samaan Ibrahim.

El-Seed’s comments to MEE confirmed this. “The only authority who knew about the project is Father Samaan who gave his approval. The whole community were then open to the idea. I didn’t reach out to any other authority. It was really a community project,” el Seed said.

Bishoy expressed a great deal of enthusiasm about the artwork and told MEE that people quickly got used to seeing eL Seed and his friends painting in the narrow streets of the neighbourhood, where residents are usually sorting, recycling, and working through Cairo’s garbage.

"It is beautiful," Bishoy said about the mural. "We didn't know what it was going to be in the end, but it was amazing when we saw it all... all the colours match well," he added.

The artist publicly praised the warmth and reception from the people of Zareeb. “The Zaraeeb community welcomed my team and I as if we were family. It was one of the most amazing human experiences I have ever had. They are generous, honest and strong people,” he wrote.

“Upon beginning the project, each building was given a number. Soon enough, each of these buildings became known as "the house of uncle Bakheet, Uncle Ibrahim, Uncle Eid,” el Seed wrote in a Facebook post.

Moussa Nazmy, another resident of the area, said that many of the residents had not known how the mural would look in its final stage, but were surprised and happy to see the results.

Left unharassed

Neither eL Seed, nor residents of the area, reported experiencing any trouble with the Egyptian authorities, which was good news for them all considering the fact that the increased suffocation of Cairo’s creative art spaces has been an issue of concern.

For instance, before the fifth anniversary of the 25 January revolution, security forces raided the downtown-based Townhouse Gallery and the Rawabet theatre, the independent news website MadaMasr reported. This was just one of a series of raids of art spaces in recent months.

The fact that the impoverished Manshiyat Nasr neighbourhood itself remains far from the controlling eyes of the state may have helped eL-Seed.

The artwork received positive responses overall. Egypt’s embassy in Washington even said on its Twitter feed that it was “totally amazed” by eL Seed’s artwork.

The privately owned pro-state TV channel, ON TV posted a photo of the mural with a caption that stated “the main streets of Manshiyet Naser have been developed”. One user commented that “Cairo’s governor is attributing to itself the efforts of a respectful artist who took from his time, money, and energy to do something for the country and for the poor… why are you surprised?”

Shehata al-Muqades, a union leader for Cairo’s garbage collectors, told MEE that he thinks the artwork is “very beautiful” and that “it gave a sense of importance to the garbage collectors”.

A community made vulnerable

According to Muqades, there are almost one million people doing work related to garbage collection throughout Cairo, and there are approximately 15 tons of trash coming in from across the city that are recycled daily in Manshiyet Naser.

The garbage collectors have been living in the Manshiyet Naser neighbourhood since 1970, but have been in Cairo since 1948. “Our fathers and grandfathers are from Upper Egypt,” he told MEE.

“They are from provinces like Assiyut, Sohag and Menya,” he added.

Workers in the garbage sector have been made especially vulnerable at various moments throughout the past two decades.

For example, in reaction to the swine flu epidemic, ousted president Hosni Mubarak’s government killed tens of thousands of pigs. Nazmy told MEE that the slaughtering of the pigs was not only “stupid,” leaving thousands of families whose livelihoods depended on the pigs devastated, but it was also “inhumane” to the brutally slaughtered creatures.

Pigs have slowly and informally begun to reappear in the neighbourhood, but the 2009 mass culling took its toll on the Coptic Christian residents for years afterwards.

Residents have also had to face relentless competition from multinational companies when the Mubarak government signed 15-year municipal contracts for waste collection with Spanish and Italian companies in early 2002, in a move to industrialise the garbage sector, Muqades told MEE.

“These companies may have equipment but they do not have the labouring hands of the residents,” Muqades said, adding that the state’s dependence on the companies has been really “unjust” to Cairo’s garbage workers. The contracts are due to end in February 2017, and according to Muqades the government promised not to renew them.

Yet despite debilitating conditions for Manshiyet Naser's residents, Muqades sees a poetic aura in the artwork, stating that it highlights how “beauty lies behind the piles of trash”.

For now, el-Seed plans to go back to the neighbourhood when he launches a book about the project. “We will distribute in the neighbourhood to all the people we met and who were part of the adventure. A documentary is being edited right now. We will display it there as well.”

“The idea was to bring something positive,” el-Seed said. “They loved the fact that we were interested in them. Sometimes, you need someone from outside to tell you how beautiful you are.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].