Israel’s godfather of design draws crowds to a graphic history of the state

TEL AVIV, Israel - There is a purple brick building on the central approach to Tel Aviv that stands out from its flashy, mirrored surroundings, bearing the message "Art Saves us From the Truth." The story-high, bright yellow letters paraphrase Nietsche, but also paint a wryly precise picture of Israel’s financial and cultural hub. Here, amidst the art and commerce, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict can feel very far away, even though the occupied West Bank lies less than 30 kilometres east.

Tel Aviv is where David Tartakover, Israel’s godfather of graphic design, has made his home and studio for the better part of his 72 years. And as an artist, he is not trying to save anyone from the truth – he is trying to depict it.

Nowhere is this better displayed than at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art’s summer retrospective of his work, simply titled: Tartakover: The Exhibition. The sprawling show, which runs through October, is filled with posters, drawings, collages, photographs and ephemera that have been burned into Israel’s collective conscience; a result of Tartakover’s commitment to documenting Israel’s history by mixing popular imagery and text.

It is quickly proving to be the Museum’s most popular exhibition of the summer, in part because visitors can recognise both personal and shared history in the varied imagery.

“They didn’t expect it to be such a success!” Tartakover said shortly after the exhibition opened at his studio in Tel Aviv, referring to the museum with a smile. He is clearly pleased at the overwhelming numbers of visitors, which he counted as being in the thousands. “There’s a lot to do in this show. You can spend some time there. If you want to read everything and to see and to understand, it takes time. And this is what I wanted. I wanted people to come in and spend their time.”

The exhibition

Tartakover, along with his assistant, Tali Liberman, acted as curator and exhibition designer. Once he knew the design of the space, he said it did not take long before he knew where everything would go. The only issue was not being able to show full bodies of work, which can sometimes include as many as 20 posters.

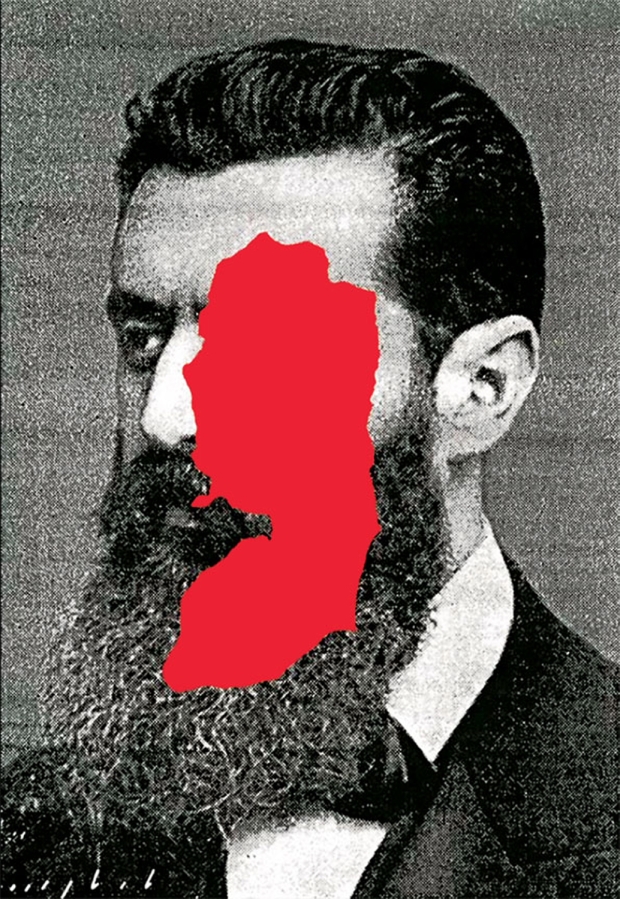

“The show is a political show, and there is no other way to look at it,” Tartakover said. “Graphic design for me is a tool to express myself and to give answers to current political cases that happen in Israel. I’m not a protest artist – my work is a reaction. I react to the situation around me, through my posters and other things.”

Many are familiar with Tartakover’s most famous pieces. His 1978 logo for Peace Now, or Shalom Achshav - the Israeli liberal advocacy group - hangs high at the centre of the space. Nearby, his simple, text-based design for the 1985 film Shoah hangs near a screen print depicting a group of schoolchildren facing a group of Palestinian men in traditional dress. They are separated by a thick band of green – a "green line," referring to Israel’s pre-1967 de-facto border with the Palestinian territories. In striking contrast, the border of the poster illustrates the words to the Israeli song I Love You, My Homeland.

Irith Hadar is the head curator of the prints and drawings department at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and oversaw the hanging of the exhibition. She said that Tartakover’s success as an artist lies in the way he leaves familiar phrases open for thinking and re-thinking, rather than telling his audience what they should be thinking.

“Taking a phrase and opening it to new interpretations is part of the way he works,” Hadar said. “The way he combines text and images relies on meanings, and what both the image or the phrase accomplish,” she added.

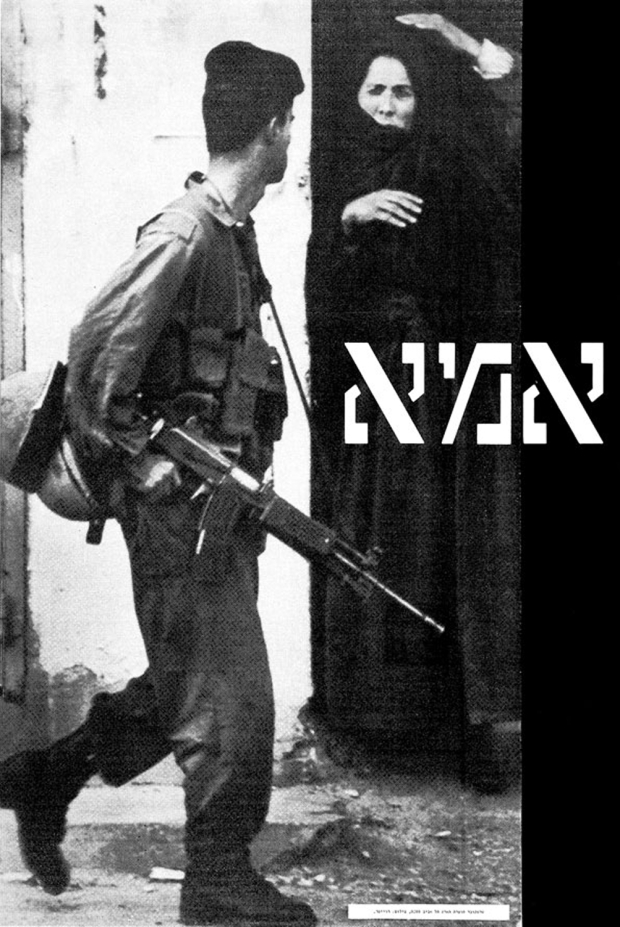

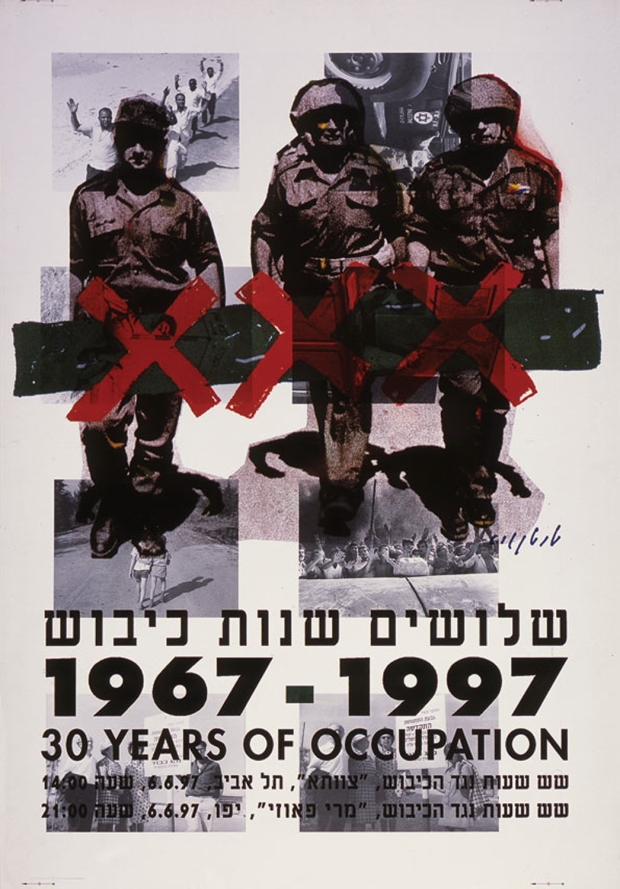

On one of the most arresting walls, his 1988 poster depicting a black and white news photograph of an Israeli soldier returning the worried gaze of a Palestinian woman is overlaid with the word Ima, or mother, in Hebrew script. The image, which came to symbolise the First Intifada, takes its place among anniversary posters chronicling Israel’s occupation of the Palestinian territories since 1967.

“I use cheap photography right from the newspaper,” Tartakover said. "I would take the photographs that I like and I would xerox it and enlarge it to do whatever I want with it. I loved working this way, not thinking about the design, but thinking about the impact. It came from the street as a newspaper, I did whatever I did with it, and send it back to the street. As a poster, it has a different meaning.”

Completing the Tartakover trilogy

Tartakover was born in 1944 in Haifa, and grew up in Jerusalem. He had the idea that he wanted to train in art and design, and after completing his military service with the paratroopers, studied at Jerusalem’s Bezalel School of Art and abroad at the London College of Printing (now the London College of Communications). He returned to Israel to begin a short-lived career in television, and then advertising, and eventually opened his own studio in Tel Aviv. Even in light of his sometimes controversial and politically critical work, he was awarded the country’s top honour, the Israel Prize for Design in 2002.

Tartakover sees the retrospective as the final instalment of a trilogy that began in 2010, with Scachar Rozen’s documentary Tartakover. The second instalment came in the form of a book, published by Am Oved in 2011. The more-than-500 page book is a Tartakover encyclopaedia, and one he continuously refers to when pointing out how he had to pick and choose what made it onto the walls of this summer’s show.

“My world is divided into three circles that touch each other and support each other,” Tartakover said, describing the motivations behind the work being shown, which he specifically did not hang in any chronological order.

“One is that I was trained as a designer, so doing work for clients, mainly for cultural institutes, publishers,” he continued. “Another one is my personal work, which is my art, my posters, non-commercial work; work that I do because I want to do it, it’s my heart. The third circle is collecting, researching the history of Israeli graphic design, which is a preservation of culture. And when I started to do it, to collect this stuff, nobody paid any attention to this stuff. So it was easy to collect and I think I have the largest private collection of posters in this country, over 3,000 in my archive.”

Collecting and recollecting

It is Tartakover’s collecting that Eric Zakim says sets him apart from other Israeli artists and designers. Zakim, who is an associate professor of Hebrew literature and culture at the University of Maryland, sees Tartakover as a participant and critic of Zionist history, using his collection as an active archive that informs his work.

“Tartakover was one of the first people, in terms of popular culture, who looked back,” Zakim said. “He started collecting these posters when no one did.”

Pieces from Tartakover’s collection fill a single wall of the exhibition dubbed "Tartakover and Friends," where visitors can get a sense of the broad range of work that inspires him, mixing folk art, old advertisements, friends’ work, and even Soviet photographs.

“There were graphic artists before him, and many after, but he does represent some sort of shift, especially in the popular visual vocabulary of Israel,” Zakim continued. “And using it for a type of expression that really hadn’t been done before, but being completely cognisant of that history. He’s a guy who really embraces that history, but that doesn’t need to see it as only leading in one specific trajectory.”

Today, Zakim and Tartakover both agree that the political poster is dead, obscured by the rise of digital media. At the same time, as the political climate in Israel shifts to the right, there is concern both at home and abroad that the government is trying to curb free speech by enacting laws that monitor cultural and advocacy funding. Tartakover notes that he might not have received his Israel Prize if the climate in 2002 had been as uncertain as it is today.

“It’s stuck,” Tartakover said of the current government, pointing out the 1988 poster series in which he erased parts of Israel’s Declaration of Independence that he sees as unfulfilled. “It’s not going anywhere, and if it’s going anywhere it’s going in the wrong direction. Without freedom of expression, you cannot have a democracy, and their is no democracy without freedom of expression.”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].