New generation of feminists strike out in Tunisia

TUNIS - Khouloud* is comfortable in her black leggings, but is trying to get rid of someone who cannot keep their hands to themselves. The 21-year-old science student is not used to self-defence classes. Like many others, she came one Saturday morning out of curiosity - just to try it out - and it is quite challenging.

“I live in el-Mourouj on the outskirts of Tunis. I often take public transportation, and to be honest, I’m sick of always being harassed. I would like to be confident enough to defend myself and talk back,” she says, catching her breath in between moves the female trainer is showing her which should be able to immobilise an aggressor.

These self-defence classes are a first in Tunis. They are free and scheduled regularly, and their aim is to help women defend themselves. “When we first started these classes, it was mainly to help women to protect themselves against harassment on the streets,” Rym Amami, a member of the CHOUF association, tells Middle East Eye.

Created in 2013 by a group of young women, CHOUF’s first purpose was to defend women in Tunisia. Then it expanded to reach out specifically to women from marginalised backgrounds, such as prostitutes, and finally it expanded to all women who are victims of an ever more oppressive daily life in Tunisian public space.

Direct actions to claim back public space

The three students here today are beginners and they get scared when the trainer shows them a few moves, which are a combination of kick boxing and martial arts. “What you need to bear in mind is that the aggressor is as scared as you are, and so by reacting you will actually surprise him, which is always a good thing for you since he will be caught off-guard,” she explains to the girls imitating an aggressor’s body language.

Techno music is playing in the background and the female trainer, who did not want to be interviewed nor disclose her name for security reasons, is conducting the class with an iron fist.

Inès Ellouze is in her sweat suit and is wiping the sweat from her brow. The 33-year-old graphic designer with short hair has become addicted to the classes. She comes every Saturday and is even taking private lessons with the trainer.

“I love the concept, but above all, it gives me confidence. After each class, when I get home, I practise with my husband, and it does work I have to say, even though I’m way shorter and less heavy than he is.”

Ellouze does not consider herself a feminist, but she deplores the fact that she is not able to walk down the streets while smoking and wearing whatever items of clothing she wants. “You will always get a bad look for wanting to live the life you want, which makes you feel like even more of a minority here,” she tells MEE.

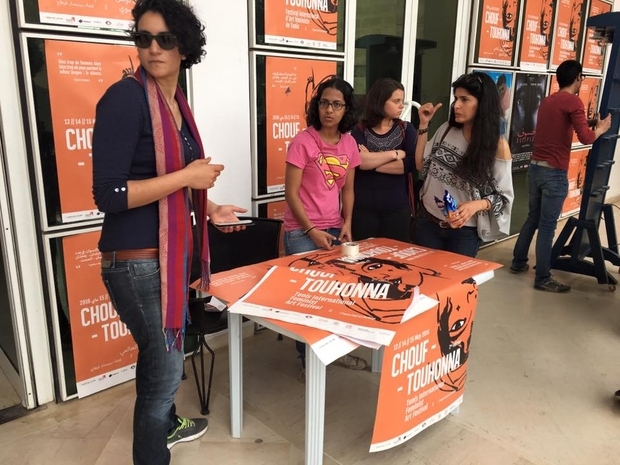

Those individuals are the ones CHOUF wants to defend by raising awareness and opening up debate. Last May, in partnership with another association called Chaml, they organised the Chouftouhonna Festival, dedicated to feminism and how it is expressed through art.

“The idea was to create a place where women can express themselves without being censored and where other women's associations can join forces,” says Dorah Mongalgi, member of CHOUF and co-founder of the festival. For the interview, she insisted on meeting with us in the cheapest coffee house in the very upper-class neighbourhood of Ennasr in Tunis where women would not traditionally frequent.

It is Sunday afternoon, and there is a football game on. The majority of the clients there are men, but Mongalgi could not care less. Like other feminists, she is claiming back those places that are a symbol of gender segregation.

Mona Dachri Bouzaiene, a 28-year-old legal expert, has published a hidden camera video dedicated to this practice on an edgy Tunisian TV show called RDV9. Women are stepping into coffee houses where there’s usually only men.

“Gender discrimination is so common in Tunisia. Many people think that it's abnormal to have places dedicated to men only, like those ‘popular coffee houses’. However, no one has ever said anything about it. We have been raised in a society that considers it ‘normal’ and we’ve learnt to accept it,” she tells MEE.

The video got 59,000 views. Another one had a huge impact too, where a young woman is pretending to harass men in the streets, giving them a taste of their own medicine.

Fighting clichés and taboos

In Tunis today, the status of women and their image remains a hot topic, as we can see from street billboards. Chaml analysed them on its blog. The wedding season hits its peak after Ramadan and beauty salons offered package deals that will turn you into a princess for 1,500 dinars (around $800), which is five times the average salary.

“There are still many clichés surrounding Tunisian woman that need to be torn down,” declares Hajer Boujemaa, a member of Chaml. The image of Tunisian women has been tarnished by Leïla Ben Ali (wife of former Tunisian president Ben Ali), who left her mark on how women and feminism are viewed in Tunisia. The stereotype of the manipulative and materialistic social-climbing hair-dresser has been exaggerated by some after the revolution in order to blame the fall of the regime on the dictator’s wife and her family rather than on Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali himself.

Some feminists feel that in order to destroy those clichés, women have to start to pick up the pen and write themselves. Among them is student Sabrine Ghannoudi; every month in a coffee house she organises a writing workshop called Notre-Dame-des-Mots, where about 25 women come and express themselves through poems and other personal texts.

“We talk about everything. There are women from Gabès (south of Tunisia), from Tabarka (north of Tunisia) and from Tunis too,” says Ghannoudi to MEE. Men can also participate in the workshops. “Themes like: motherhood, the nation, sexuality and taboos are predominant. Many women express their pain towards forbidden things,” says Ghannoudi, who was not expecting such success when she started the events.

Breaking free from the old generation and Western feminism

Social media, direct actions and raising awareness are tools that differentiate this new generation from the older Tunisian feminists, who used to focus on activism and defending legal rights.

Bochra Bel Haj Hmida, former activist of the historical Association des Femmes Démocrates (ATFD), views this success positively. She is an MP and is still very involved in issues concerning the status of women in Tunisia.

“NGOs are here to put pressure. Like when the bill for equality in inheritance was discussed in parliament. It is important that they lobby and use tools that shake up the rest," she tells MEE. The bill aims to modify the current law which states that men inherit more than women.

Even though CHOUF and Chaml are quite different historically, neither deny their legacy. “They were blamed for many things, such as being too elite-oriented and not being inclusive towards some women, nevertheless, we owe them our current rights,” says Mongalgi.

She insists on the fact that the fight has to go beyond Tunis. Journalist Charlotte Bienaimé explains it in her book Féministes du Monde Arabe (Arab World Feminism). She says that women in other regions do not have a platform yet. Like Houda who hosts a radio show dedicated to women in Gafsa called “La Voix des Mines”; or Ghofrane who campaigns for women from the Kef region, these activists are still under-represented among the activist population in the capital.

“We want to change that. We need to be in touch with those people in other regions where economic disparities are priorities for women,” says Mongalgi.

What these women have in common is the fact that they don’t focus on “Western” issues. “For instance, beyond the veil issue, which is a focus in Western countries, these young feminists are more concerned about joining forces, wearing the veil or not, like female demonstrators did during revolutions,” Bienaimé wrote in her book.

Towards the end of state feminism?

Another breaking point with this new generation of feminists lies in state feminism. It was ordered by Bourguiba and carried on by Ben Ali and consisted - as it still does - in giving rights to women based on 1956 legislation. But no one is fooled - it is only to show a democratic facade.

As historian Sophie Bessis says in her article Institutional Feminism in Tunisia, the emancipation of women does not come without conditions within this context: “In return for his ‘concern’ towards women's issues, the president demands their unconditional support. They have to participate in national activities at every level. Their emancipation has boundaries tied to religious values and last, but not least, they have to actively fight Islamism.”

Following the revolution, Béji Caïd Essebsi, current president of the republic, used that banner during presidential elections to gather up women voters without giving them more rights once he got elected.

Therefore, until today, there is a dichotomy between the official speech provided by the state and the reality of everyday feminism in Tunisia. Feminists no longer want to follow values that have been forced on them. Many have been disappointed since the revolution.

“A certain idea of feminism was forced on us, as if Tunisian women can only be of one extreme or another, either Meherzia Laabidi or Amina Sboui, which is nonsense because Tunisian women are everything at the same time,” claims Hajer Boujemaa, referring to Ennahdha’s MP Meherzia Laabidi who represents a conservative image of women, and Amina Sboui, former Femen member, who stirred up controversy by appearing topless.

Women in parliament

Despite this new feminist movement’s weaknesses and lack of structure, there are more and more actions and diverse initiatives that reach up to the highest political level. Twenty-eight-year-old Sayida Ounissi, a member of the Islamist Party, has raised her voice many times in parliament in regards to gender inequality in politics.

“When we see what’s happening in France where female MPs are fighting against harassment, we believe we need to set up similar actions here. Quite often female journalists and politicians become the subject of unpleasant remarks and sexist comments from their male counterparts,” she says. But for her, change has to be made gradually and not imposed, as the mentalities need to be changed. “For instance, about the bill for equality in inheritance, every single political party needs to enter the debate and bring forward proposals,” she adds.

Four years ago, her party proposed a bill which emphasised that the roles of men and women are meant to be complementary and not competing, but it did not make it to the Tunisian constitution since a lot a people were against it. Today, Bochra Bel Haj Hmida and herself are bringing forth the debate about how women within parliament should be truly supportive of one another regardless of their party affiliation.

Proportionally, Tunisian parliament has more women (31 percent) than the French one (26 percent). However, there are only three women members of the current government, despite the fact that its president got elected thanks to the votes of a million women. Long is the road for Tunisian feminists.

*The person who was interviewed asked to remain anonymous and not to disclose their family name.

Translated from French (original) by Nassima Demiche.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].