Assad may take Aleppo – but then he faces a war against the victors

President Bashar Assad’s forces are further consolidating their presence in the war-torn city of Aleppo where the area occupied by a besieged opposition shrinks day by day.

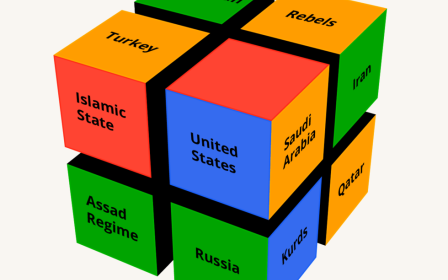

While the Aleppo battle appears to be strengthening Assad’s position as Syria’s leader, the sheer complexity and diversity of the forces fighting there underline the regime’s brittle decentralisation as a result of manpower shortages and the system’s growing militarisation.

In a recent interview with AP, Assad declared he would not stop until he regained control over all of Syria. If Assad captures Aleppo, he would technically be in control of Syria’s three largest cities - Damascus, Homs and Aleppo - and thus reinstate his authority.

Yet Assad’s hegemonic status has been eroded by manpower shortages and the growing influence of a wide array of militias whose loyalties often lie outside of Assad’s direct sphere of control.

Native shortfall

As of 2013, Syria’s army had lost half of its forces, shrinking from 220,000 before the war to approximately 110,000, according to International Institute for Strategic Studies estimates.

By last October, over 70,000 men had skipped their compulsory military service in provinces controlled by the regime, Now Lebanon reported. The latter reacted by adopting a two-pronged approach, either arresting youth or imposing mandatory conscription to state employees, teachers and prisoners.

To offset the bleeding, the Assad regime has become in large part reliant on militias, whether provincial, religious, linked to political and army bodies, business figures or foreign-backed.

According to Syria expert Aron Lund, the National Defence Forces (NDF), the largest militia network in Syria, was created through the rebranding and restructuring of local Popular Committees and seems to act with considerable autonomy.

Researcher Aymen Jawad Tamimi has identified other militias that exist alongside the NDF. Some militias have a religious base, for example, local Shia militias which, according to Tamimi, are linked to Hezbollah. These include Quwat al-Ridha or Liwa al-Imam al-Mahdi.

Some, such as Liwa al-Sayyida Ruqayya and Liwa Sayf al-Mahdi, are linked to the Syrian army’s elite Fourth Armoured Division. There are also Christian militias such as Quwat al-Ghadab and Sootoro.

Second, there are militias affiliated to business figures such as Assad’s cousin Rami Makhlouf and the charity he owns and runs, Al-Bustan Association, namely, Kataeb al-Jablawi, Deraa Alwatan and the Leopards of Homs.

Third, Tamimi has listed several militias affiliated to political parties and intelligence services such as the Lions of the Eternal Leader, Fawj Maghawir al-Badiya, Quwat Dir' al-Amn al-Askari; some affiliated to military security, including Lions of the Euphrates (Amn Dawla) and Tiger Forces (Air Intelligence); and finally the Baath Battalions.

“These militias operate to a large extent within the structure of the government or the provincial council or the army,” says Maen Tolla, a researcher from Turkey-based think tank Omran Dirasat.

Foreign fighters to the rescue

According to an AFP article, about 7,000 Iranian Revolutionary Guards are deployed in Syria while a group of 3,000 Iraqi volunteers from Abu Fadl Abbas currently defend the Shia holy site of Sayyida Zeinab south of Damascus.

Another 3,000 Afghan "Fatimids" have fought in Deraa province in the south and 7,000 Hezbollah fighters have played an instrumental role in Qussay, Qalamoun and now Aleppo, according to sources within the party.

Additionally, last month about 1,000 fighters from the Iraqi Haraket Nusjabaa, a Shia militia, was sent to Aleppo. Another foreign party, the Lebanese Syrian Socialist National Party (SSNP), has been involved in Syria under its armed wing Nusur al-Zawba’a (Eagles of the Whirlwind) which guarantees security in several Syrian towns including Homs, Latakia and Wadi Nassara, according to Tamimi.

The regime's growing dependency on local and foreign militias is slowly building the potential for a complete breakdown of order, with militias having either competing backers or different localised agendas. This phenomenon is more specific to militia groups created or financed by wealthy patrons or foreign players.

Illustrating this rivalry is the case of Kata'ib al-Jabalawi, a Shia militia which harbours hostility to the Syrian army and all the battalions and militias loyal to it, including Hezbollah, according to Tamimi’s reports.

Syrian sources have also reported clashes between loyalist militias such as the Desert Hawks and the Air Force Intelligence-affiliated Tiger Forces over diverging economic interest and territorial control. Similar incidents have taken place between the NDF and other militia forces in Qalamoun and between Hezbollah and the Syrian army in Aleppo.

According to rebel accounts, mistrust also prevails between pro-regime factions, which prefer to handle each quitaa (military division) independently from one another. A leaked recording of a Hezbollah fighter in Aleppo, accusing allies of having fled the battle, is a case in point.

Pyrrhic victory?

Assad may remain for now the arbiter to many of these militias. “He has the power to reach out and punish when needed,” says Jihad Makdissi, who acted as the regime spokesperson before his defection in 2012.

However, Assad will be increasingly forced to compromise with newly empowered militia commanders if he is to retain their support. Militia commanders will be naturally gaining more autonomy as state funding declines and the more capable they are of creating a system of taxes and extortion in areas under their control.

In addition, militias affiliated to foreign backers such as Hezbollah or Iraq’s Hashd al-Shaabi may prove to be more loyal to their international patrons. This system’s militarisation has translated to the political scene with parties pushing for more influence. For example, Liwaa Baqer and the SSNP were able to secure seats in the last parliamentary elections, points out Tamimi.

Assad’s gains in Aleppo may grant him the credibility he is looking for, yet it may be another pyrrhic victory as he may now have to contend with many allies and powerful lieutenants.

- Mona Alami is a researcher and journalist covering Levant politics. She is a non-resident-fellow at the Atlantic Council. Her primary focus is radical organisations. She holds a BA and an MBA in management.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: A Syrian pro-regime fighter walks in a bombed-out steet in Ramussa on 9 September 2016, after fellow fighters took control of the strategically important district on the outskirts of the Syrian city of Aleppo the previous day (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].