Beaufort Castle: Israeli stronghold, Lebanese resistance, Kuwaiti money

ARNOUN, Lebanon - High above an olive grove and the Litani river, a group of Beiruti women are standing on the bridge of a Crusader castle, squabbling.

“Where is Israel?!”

“Where is the border with Israel?!”

“Take a picture of Israel!”

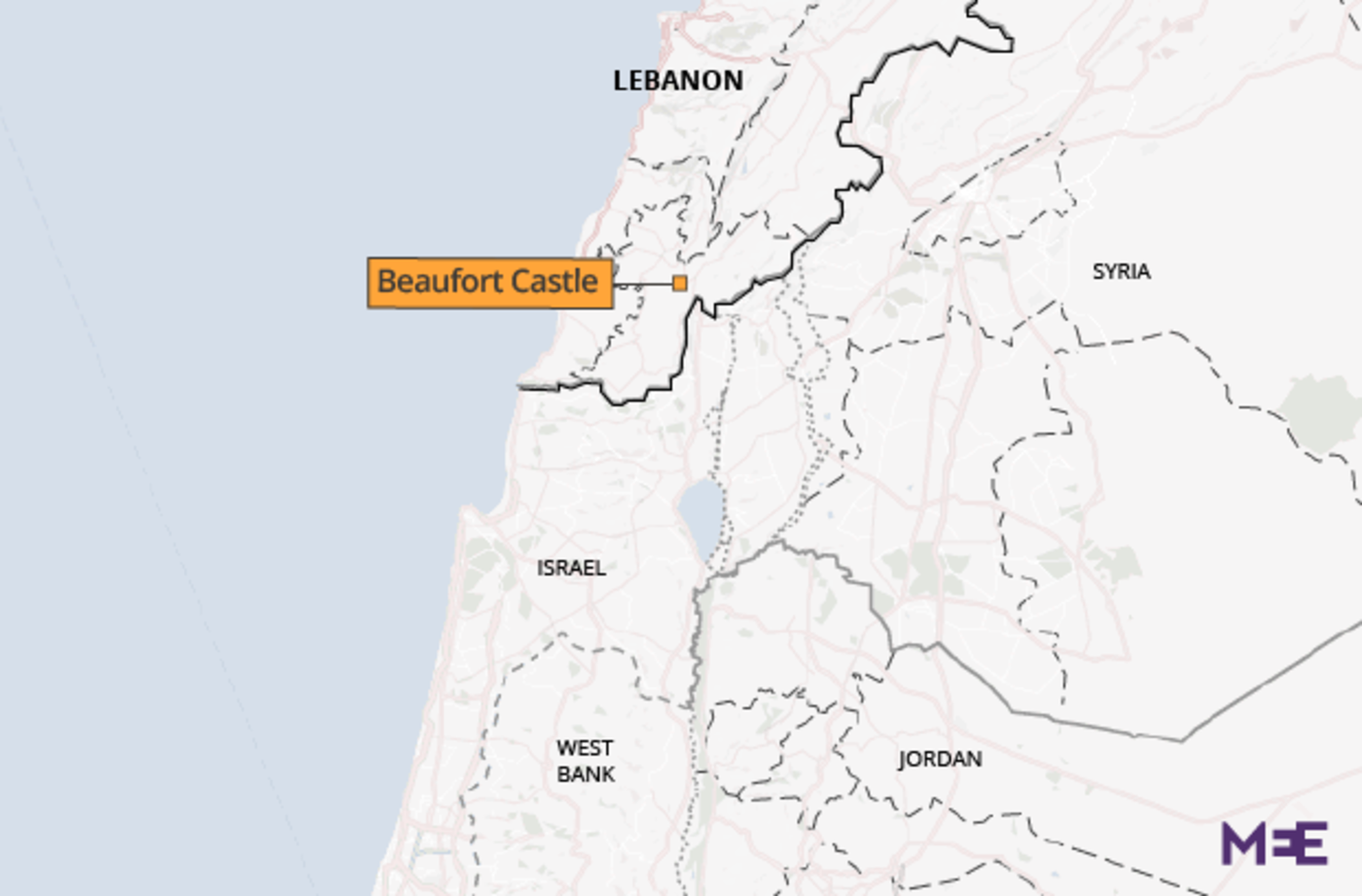

From a 700-metre bluff overlooking Mount Hermon you can look out and see Lebanese villages and, somewhere behind a hill, the Israeli border lies. A complicated history rolls through Beaufort Castle’s rough stone walls.

To the east, a sheer precipice drops 300 metres to the valley floor. From Beaufort’s lip, the Litani looks like nothing more than a sprinkling of water trickling between the greenery.

The fort itself, overlooking the contested and occupied Golan Heights, Palestine, Mount Hermon and Lebanon’s southern coastal plain, has had more than a turbulent history.

Serving in military campaigns nearly 1,000 years apart, Qala’at al-Shaqif, as it is known in Arabic, has been held by Crusader, Arab, Ottoman, Palestinian and Israeli forces.

Qala’at al-Shaqif, as it is known in Arabic, has been held by Crusader, Arab, Ottoman, Palestinian and Israeli forces

Now, 16 years after the end of the occupation, this prized military fortress is helping to dispel myths about the country’s southern reaches among Lebanese and foreigners alike.

Although the Syrian conflict is not far away – “From here we can hear the shelling from the Jawlan between the rebels, the Syrian regime and Israel,” says site guard Ali Hamdan, who is originally from the area and now lives near the castle – Beaufort is as peaceful as it has perhaps ever been.

“Even Lebanese [people] are sometimes scared to come here but south Lebanon is the safest, friendliest and most beautiful place in the country,” Hamdan insists. (The UK Foreign Office still advises against all but essential travel south of the Litani river, although it considers the area around Beaufort safe).

Daytrippers are visiting Beaufort in increasing numbers: up to 1,500 climb up to the lofty site at weekends and on holidays.

The hope is that a $3.5 million excavation and restoration project, begun in 2009, will attract more tourists to this corner of southern Lebanon, around 8km from the Israeli border. A long-anticipated visitor centre is still to materialise, however, and excavation work is ongoing.

Crusader fortress

Fulk, King of Jerusalem, captured the site on which Beaufort now sits in 1139. Someone – it remains unclear who – had obviously realised its strategic use, as a tower had already been built on the hill when he arrived.

According to Professor Hugh Kennedy, building on Beaufort – “beautiful fort” in French – began very soon after Fulk’s arrival.

“Beaufort is a fine piece of castle,” says the professor of Arabic at SOAS University of London, also an expert on Crusader history. “But [in the region] we must not think of a network of castles but as Beaufort as a centre of a Frankish lordship in a feudal society, using the castle as a way of raising money.”

Inner bailey walls and entrance arches from the Crusader period survive, and have been restored using the original stone, which lay in heaps around the site after the Israeli occupation. A bowl resembling a giant mortar, apparently dating from Crusader times, sits to one side; now the walls have been rebuilt and the weeds cleared, it is easy to imagine it in use.

Traces of the Muslim period are still visible too, to the beady-eyed. On the wall built during the Arab era, one stone is faintly inscribed with the word Allah – God.

During the excavation stages of work on the castle, teams from Lebanon’s Directorate General of Antiquities (DGA) uncovered artefacts that reveal details about daily life during the Crusader period and later, included pots, coins and jars. Arrows believed to date back to the 12th century were also unearthed, while the barrage of modern artillery uncovered – including shell cases and rockets – shows the longevity of power plays around Beaufort.

Israeli target and military base

Any military man worth his shield or shoulder stripes would want this place.

“It is not a position you would have wanted to inhabit unless you wanted to defend yourself,” Professor Kennedy explains.

Much later, Beaufort would not survive the 20th century unscathed either. Even before the 1982 Lebanon War, which saw Israel invade its neighbour, the Israeli Army's Northern Command had wanted to capture the castle.

But by the late 1970s, the opposition PLO had made Beaufort a significant base. According to Hamdan, the Palestinians built bunkers 65 metres underground in places at the site.

Israeli forces eventually had their wish granted during the “Battle of the Beaufort” in June 1982, after heavy shelling of the castle.

“Most of the damage was from them,” says Hamdan, solemnly.

“This was the strongest and biggest of Israel’s military positions in south Lebanon; you can see on all sides.”

Wedged into one of the castle’s pale stone walls, on what is now one of the upper levels, lies an unexploded Israeli shell case – potentially a nice piece of propaganda for displaying the Israeli Army's assault on the castle. However, until now, there are no bombastic descriptions of “Zionist aggression” or other bellicose language on any of the site’s few information boards.

Holes gouged by various missiles – whether left deliberately gaping or not – are obvious. One sits like a stab wound on the castle’s outermost wall, beside which, Hamdan explains, Israeli soldiers built a trench. Another leaves the wall crumbling away opposite newly reconstructed underground corridors and rooms in the Crusader-era part of the castle.

The most impressive are on the castle’s eastern side, facing towards the Shebaa farms in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. These five-metre-wide cavities are large enough to star-jump through – and while they provide excellent viewing posts out on to the shoulders of Mount Hermon in the distance, they carry the grim reminder of artillery’s power to destroy man and mortar.

Just as the Crusaders did centuries before, the Israeli Army added to the site as they saw fit. Beside the castle now sits an ugly sharp-edged bunker and a network of tunnels leading to grey concrete look-out posts.

Yet today, with the castle firmly in Lebanese hands, a yellow plaque on the bunker reads:

“At Qala’at al-Shaqif, Arnoun: we remember the blood of the martyrs who liberated the land.”

Martyrs of 1982

Death tolls from the Battle of the Beaufort vary, but six Israeli soldiers are thought to have been killed, and more than 20 Palestinian fighters.

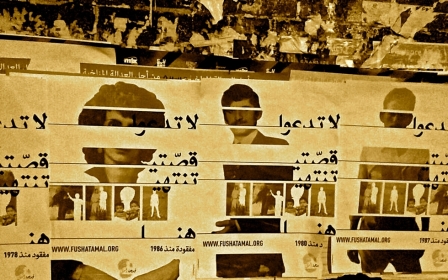

It is important for locals that the rest of Lebanon remembers how the communities here suffered during the occupation.

It is important for locals that the rest of Lebanon remembers how the communities here suffered during the occupation

Pointing down to the Shia village of Arnoun, which clusters at the foot of the castle hill, Hamdan explains: “All these houses are new; Israel destroyed them all, everything except the mosque. But today south Lebanon is among the safest parts of the country.”

Samir, an Arnoun villager who gives his first name only, said that he saw many air strikes on the area around the castle. “It is a good thing that it is being restored. It is part of our history.”

May, a Lebanese-Australian woman on holiday who gave her first name only, had never been to this part of Lebanon before. “But just look at it – it is a beautiful place,” she said.

"Our friends told us about this place [Beaufort Castle] and I should tell my kids to come here. Look how thick and tall and strong the walls are.”

“Lots of people here remember the wars,” says Hamdan. Another poignant reminder is a mural in Arnoun: an Israeli Army soldier is illustrated being booted sideways by Arabic letters spelling the village’s name.

Modern tourist attraction

Today, although the Lebanese Army has a site nearby, visitors arriving on coach tours or groups of school pupils are more common than soldiers at Beaufort. Word is spreading about the castle’s significance and the far-reaching views to places with familiar names – Shebaa, Palestine, Jawlan – that many of the tourists here cannot visit.

May, the Lebanese-Australian tourist, sighs as she remembers the arguments over the lands she is looking over: “Fights over God’s land,” she says, shaking her head.

“I would like to go to many places in Israel too,” she adds, nodding her head south. “If I go there I cannot come back here, can I? But this is a beautiful place – we will tell people about it.”

Between the pale limestone archways and slit windows dating from the Crusader period are new metal mesh stairs and barriers, which prevent most of the visitors from standing too precariously close to the sheer walls. The occasional tourist, however, wobbles near the edges, camera and smartphone in hand, for the ultimate anti-Israel selfie.

Graffiti is a problem, however. “Bedouins from Sur [Tyre] come in the night and draw. There are no guards around to stop them,” says Hamdan. The DGA did not respond to requests for comment about any possible plans to prevent vandalism at the site.

Funding had to be brought in from abroad to allow the restoration to progress as far as it has. Around $2m was provided by the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development. A large sign at the entrance places a Kuwaiti flag next to Lebanon’s famous red, white and green cedar.

But since the restoration began, diplomatic relations between Kuwait and Lebanon have soured. In February, the Gulf country joined Saudi Arabia and the UAE in enforcing a travel ban on Lebanon for its citizens. The original warnings resulted from what Saudi Arabia said were "hostile Lebanese positions resulting from the stranglehold of Hezbollah on the state, although Kuwait gave no reason for its decision."

The DGA did not respond to requests for comment about whether the ban would affect any potential visits by Kuwaiti officials to see the outcome of its funding, or whether the restoration project had been affected. A spokesperson for the Kuwaiti Ministry of Finance said the Fund for Arab Economic Development was not available for comment.

Politics aside, visitors continue to trickle across the bridge to the Beaufort, as the sun sinks over the villages Marjayoun, Khiam and Shebaa to the east, and Arnoun to the west. Beaufort has lived cycles as a literal meeting point of armies, nations and emotions. For now, visitors can enjoy it in peace, and argue with friends on the bridge:

“The border is here!”

“No, it is there!”

“Take a picture of Israel!”

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].