Destruction of dams: Will IS carry through with its threats?

As the fighting against Islamic State (IS) on the ground in Iraq intensifies, attention is focused on the likelihood of an impending humanitarian crisis, with hundreds of thousands of desperate civilians trying to escape the bullets and bombs.

There are also signs of an environmental disaster unfolding in the region.

Retreating Islamic State (IS) group forces near Mosul have set fire to numerous oil wells and oil-filled trenches, sending vast clouds of toxic fumes into the air and blackening the skies to prevent bombing raids by US and other forces.

Aid workers for the Save The Children working near the town of Qayyara, about 80km south of Mosul, talk of escaping civilians covered in oil residues. “Everywhere is covered in a fine dusting of black soot and grime and the children we met were covered in it,” one aid worker told the BBC.

In the longer term there are fears that IS, as it comes under ever greater pressure, could unleash a scorched earth campaign, blowing up bridges and wrecking other infrastructure such as power and irrigation systems as it retreats.

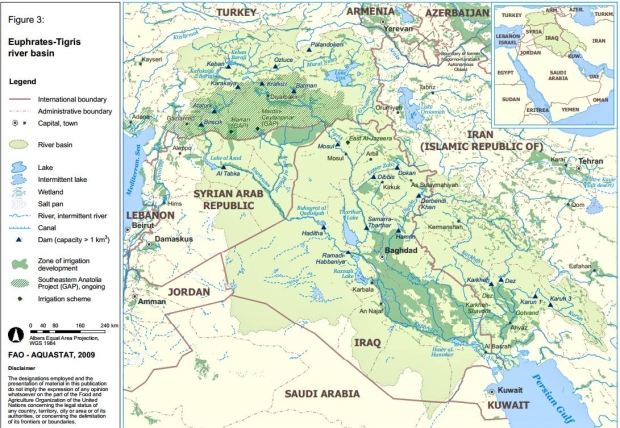

In particular there are concerns about the vulnerability of dams on the Tigris and Euphrates, the region’s two great rivers.

Why control water equates with power - and fear

Early in its campaign, IS realised that control of water and associated power sources meant it had dominance over both territory and people.

At one stage in its occupation of vast swathes of Iraq, IS had control of both the Mosul Dam on the Tigris – Iraq’s biggest such facility - and repeatedly threatened the Haditha Dam on the Euphrates.

These two dams together supply more than 70 per cent of Iraq’s electricity and control water flow to millions of people. IS also battled to seize smaller dams at Ramadi and Falluja.IS has repeatedly used dams it’s captured as weapons of war, flooding lands to deter Iraqi government forces or shutting off supplies to areas opposed to the group.

There have also been reports that IS sought to poison river waters with crude oil in order to threaten its enemies further downstream.

While all major dams in Iraq are now back in government or Kurdish-Peshmerga hands, Baghdad faces a looming problem at the Mosul facility, often referred to as the most dangerous dam in the world.

Many observers believe it would create a 20-metre high wave in the city of Mosul 50 km to the south, killing at least half-a-million people

The Mosul Dam, opened in the mid 1980s, was a pet project of Saddam Hussein, designed to enhance his power and prestige in Mosul and the surrounding area. Constructed on a base of soft, porous earth, it went ahead despite serious reservations from Iraqi and international engineers about the suitability of the site.

The dam - formerly known as the Saddam Dam - needs constant grouting and cementing to prevent serious leakages and collapse. A 2007 report by the US Army’s Corps of Engineers expressed “intense concern about the safety of the structure.”

In recent years there have been apocalyptic forecasts that the collapse of the Mosul dam would do far more damage than IS ever could. Many observers believe it would create a 20-metre high wave in the city of Mosul 50 km to the south, killing at least half-a-million people, with floodwaters rushing down the Tigris Valley, wreaking havoc in the cities of Tikrit, Samarra and Baghdad. Earlier this year the US embassy in Baghdad issued warnings about the imminent collapse of the facility.

How politics complicates repair of dam

But the Iraqi government has generally downplayed fears about Mosul. Haider al-Abadi, the prime minister, said earlier this year that a collapse at the dam was “very unlikely” while Iraqi engineers now stationed there told the Kurdish news agency that there was no cause for alarm: concerns about a breach at Mosul were based on rumours, they said.

Meanwhile, in March this year the Italian Trevi construction group was awarded a 273m euro contract by Baghdad to oversee repairs to the dam.

Tobias von Lossow is a specialist on water projects in the Middle East at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), who has written extensively on IS and its control of water resources.

Von Lossow pointed out that even though IS forces no longer control the dam itself, to a large extent they dominate the surrounding areas where gravel and other materials needed for work at the dam are found.

“You can’t make the necessary cement - and lots of it is needed to constantly inject into the structure - without access to those areas,” he says.

Baghdad faces a looming problem at the Mosul facility, often referred to as the most dangerous dam in the world

Exactly what is going on now with work at Mosul is unclear. Reporters who visited the site recently said there were few signs of activity.

The whole issue of the Mosul Dam is, inevitably, complicated by politics. The Italians want a substantial contingent of their troops to guard engineers working at the facility. The Iraqi government – and particularly the more conservative elements in the political structure – are firmly opposed to having foreign, western troops on the ground.

Dam used as a hostage prison

In Syria, the situation is no less complicated.

At present IS controls the Tabqa Dam on the Euphrates - Syria’s largest dam – and the smaller Baath Dam 18km downstream. Tabqa, built with help from the Soviet Union during the 1970s, is, in many ways, the jewel in the IS crown, feeding electricity to southeastern Syria, including its stronghold of Raqqa, 30km to the east, and water to much of northern Iraq.

Tabqa is fed by the 75km-long Lake Assad, Syria’s biggest reservoir. There are reports that IS uses the dam complex as both a base for some of its leading officials and a prison for its more important hostages:

the theory is that US or other forces would be afraid to bomb such a facility and potentially unleash a catastrophic flood.

There are concerns about how competently IS runs and maintains dams it controls: last year a Syrian rebel force, allied with Syrian Kurds, fought to take control of Tishrin dam, also on the Euphrates, from IS.

“Engineers were surprised to find IS had let the reservoir behind the dam fill almost to its maximum, creating dangerous pressure on the structure” says SWP’s von Lossow. “It’s clear IS doesn’t have the manpower and expertise to properly run such facilities.”

'Engineers were surprised to find IS had let the reservoir behind the dam fill almost to its maximum, creating dangerous pressure on the structure'

- Tobias von Lossow, German Institute for International and Security Affairs

When IS first took control of Tabqa and other dams on the Euphrates, it gained popular support by increasing power output to areas it controlled both in Syria and Iraq. Villages and towns which had been neglected by the authorities for years received electricity.

But running dams and power supplies is a complex business: IS was forced to cut back power output at Tabqa as water levels in Lake Assad dropped dramatically.

“It’s a bit like telling someone who doesn’t even drive a car to take control of a truck,” said von Lossow.

“The great danger is that as IS is squeezed out of more of its territory, there’s the possibility it could make a dramatic last stand at Tabqa and blow up the dam as a final act. That would lead to a catastrophe, both for Syria and Iraq.”

- Kieran Cooke is a former foreign correspondent for the BBC and the Financial Times, and continues to contribute to the BBC and a wide range of international newspapers and radio networks.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: An Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga guards the Mosul Dam on the Tigris River on February 1, 2016 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].