Syrians take lethal desert road to Egypt: 'We went through death to live'

CAIRO - Mohamed was clenching onto his baby girl Rokia, allowing her to feel the safety of her father's embrace while they travelled in a dusty pickup truck, speeding through the cold and dark western desert between Sudan and Egypt at more than 150 km per hour.

"I only want to live, but we went through death to live," he told Middle East Eye, while wiping away his tears.

'I only want to live, but we went through death to live'

Syrians have become accustomed to this route, which many depend on to get to Egypt, especially after Egyptian authorities tightened visa rules for Syrian nationals going to Egypt, following the military coup in July 2013.

Mohamed, 43, was once a football player in El-Wathba football club in Homs from 1988-2002, and for security reasons preferred to use his first name only.

He had to flee Syria in June 2016 after he was accused of funding a terrorist group, a charge that could have left him behind bars for at least 20 years.

Road of death

"It’s a road of death. I risked my family’s life through a rough and tiring road, where we faced a real death experience,” he said.

"But we made it safely,” his 30-year-old wife said from their home in Cairo, while putting a piece of spicy chicken on a plate, her own special recipe from Homs.

Smugglers facilitate the dangerous 22-hour journey, for a fee of approximately $400 per person.

“We had to surrender our fate to smugglers who don't care about our safety. They got their money before starting the trip," the father of three said.

A smuggler who named himself Abo Ali denied the accusation and said that he sympathises with the Syrians that he helps cross the borders to Egypt.

"The refugees we help are in a very difficult situation. They are coming from war. No single Syrian was arrested on my trips," he said proudly, adding that he smuggles around 30 Syrians a day from Sudan.

Mohamed, his wife and their three toddlers were crammed in the pickup truck along with 10 other Syrians for the terrifying drive from the coastal city of Port Sudan to Aswan, which is around 900 km south of Cairo.

'I only want to live'

In 2013, Mohamed was referred to a criminal court when he was charged with funding gunmen in a militant group. He was detained for six months, where he was tortured before eventually being released.

"The charges are baseless and if I was arrested again, they would have tortured me until I confessed,” he said.

On 26 June 2016, Mohamed fled to Lebanon before the final verdict was issued against him.

After securing $3500 from the sale of all of their possessions and borrowing some money, his family joined him in August.

They paid $1700 for airline tickets from Beirut to Khartoum, as a visa is not required for Syrians to enter Sudan.

The family arrived on 7 September 2016, and one night later they took a 12-hour bus trip to Port Sudan city on the borders with Egypt.

During the journey, they were pulled over by five Swahili speaking gunmen dressed in plain clothes, according to Mohamed.

To this day, Mohamed is still not sure what the gunmen wanted, but he remembers how terrified he was and how tightly he held onto his wife’s hands while trying his best to hide his wife's face, fearing sexual violence against her.

"I feared that they would kill me and rape my wife or at least steal the remaining 500 dollars I had with me," he said.

Eventually the pickup truck was allowed to pass through safely. When they arrived at Port Sudan, they stopped at the foot of a steep hill that they had to climb to get to the other side, where another pickup was waiting to drive them to Aswan.

"It was so hard for me to carry my children up and down the hill,” Mohamed said, adding that he felt death was near many times.

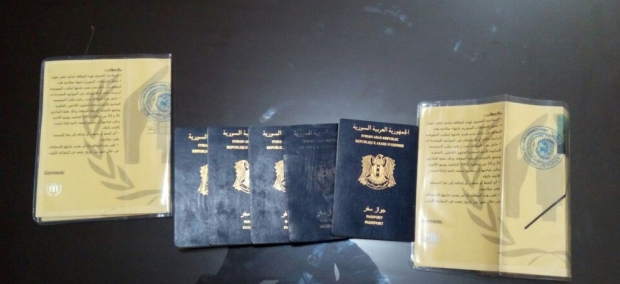

To get legal status in Egypt as an illegal immigrant, Mohamed had to apply for what is known as the yellow card from the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

On 22 November 2016, he got an accommodation visa with his UNHCR yellow card.

'We are safe in Egypt now'

Despite the dangerous journey, many Syrians prefer to take the risk and venture through the Egyptian border rather than stay in Sudan.

"The Sudanese are very kind but we are much closer to the Egyptians,” Mohamed explained.

"Egypt is more developed and its economy is more flourishing and can include us,” he added.

Radwan, 47, who is a driver and a father of five, decided to take the risk to flee Syria after his 19-year-old son Nour was officially summoned to join the Syrian army last November.

Radwan, who asks to give his first name only, lives in an apartment in the city of Obour, 35 km east of Cairo.

"I didn't want him to join any army. I cannot imagine losing my eldest son," he said while looking fondly at Nour.

To finance the trip, Radwan sold two of his trucks for $5000, which is $4000 less than their actual value.

He paid $2100 for plane tickets from Damascus to Khartoum. Then he paid the reduced cost of $350 per person to smugglers to get him and his family to Egypt. He said that the costs usually go down during the winter season.

The hopes of the big family were loaded into a pickup that drove through the freezing desert in December 2016.

"It was freezing, we couldn't resist the cold, but it was worth it. We are safe in Egypt now,” he said.

'It was freezing, we couldn't resist the cold, but it was worth it. We are safe in Egypt now'

"It's a completely unsafe trip; anybody who fell out of the pickup would die immediately. The border guards shoot any moving targets at night," Radwan added.

90 percent declined

In July 2013, five days after President Mohamed Morsi was toppled, Egyptian authorities tightened procedures permitting Syrian nationals into Egypt.

Egypt announced that Syrians needed to obtain visas and security clearances prior to their entry.

On 8 July 2013, authorities turned away 190 Syrians that arrived at Egyptian airports, hoping to enter the country without a visa, like they did under Morsi's rule.

A source at the foreign ministry, who preferred to remain anonymous because he was not permitted to speak to the media, told MEE that more than 90 percent of security clearance applications for Syrians are declined by security officials.

The official, who closely works on the Syrian issue, said he is aware of the routes taken illegally by Syrians through Sudan, but declined to give further comment.

Egyptian authorities have arrested tens of Syrians who were crossing the borders with Sudan, which has received 100,000 Syrian refugees since 2011, according to estimates by Sudan’s Commission of Refugees (COR).

No bribes no entry

Entry visas are issued after acquiring security clearance, a measure that has opened doors to corruption and bribes, according to many Syrians.

Abdel Razik, a 42-year-old father of three children, wanted to reunite with his wife, two daughters and younger son Hazem, who have been in Egypt since 2013, while he has been living in Ankara.

Razik said he had to pay a 3000 euro bribe through a broker to security officials in Egypt to get his security clearance and then his visa.

He arrived to Egypt by plane in May 2016.

"I had two options, either to risk my life or to do my best to secure 3000 euros," he told MEE in his family house near Maadi in south Cairo.

The Interior Ministry official denied any accounts of bribery.

Fears of terrorism

Egypt hosts about 116,000 Syrians according to UNCHR figures, but the actual number could be higher.

The flow of Syrians drastically fell after reaching their peak between 2012 and 2013, following visa restrictions.

"Egypt’s procedures to regulate the entry of Syrians are to prevent the infiltration of any jihadist elements claiming to be civilians fleeing the war,” an official at Egypt’s Interior Ministry, who preferred to remain anonymous because he was not permitted to talk to the media, told MEE.

'She fled death in Syria to a worse death in Egypt’s desert'

The official added in a phone interview that "the whole region suffers from instability, and terrorist elements may move to Egypt to carry out terrorist attacks, so we require a security clearance for all refugees".

He pointed out that the door was not completely closed and that Syrian husbands and wives of Egyptians and children of Egyptian mothers are excluded from the security clearance requirements, and are granted visas from diplomatic missions directly.

Local media reports have referred to the involvement of some Syrians in demonstrations supporting the Muslim Brotherhood, which was banned and labelled a terrorist group in the country in 2013, as possible reasons for restrictions.

Death in the desert

In March 2016, a pickup driver fell into a deep valley as he was trying to evade an Egyptian border checkpoint, killing 11 Syrians, according to identical accounts from many Syrians in Cairo.

Abo Negm, 54, said he lost his 72-year-old mother in the accident.

"She fled death in Syria to a worse death in Egypt’s desert," he painfully said.

He found his mother's corpse in a northern Egypt hospital after searching for four days.

"This is haram (forbidden). What kind of harm can a very old lady cause to the Egyptian national security when she only wants to reunite with her sons,” he angrily yelled.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].