If Trump keeps this up, Yemen’s quagmire could become a real proxy war

Details have emerged about the first military action under the newest US commander-in-chief: a "botched" raid in rural Yemen, considered while Barack Obama was still in power, but executed by Donald Trump in a manner best described by one of his own favourite words – bad.

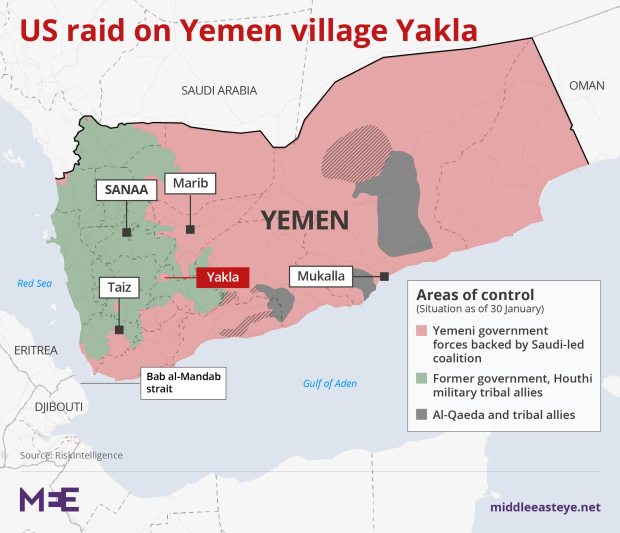

Denounced widely as a failure, the ground raid in Yakla killed 25 civilians including nine children, while missing a supposed target, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) leader Qassim al-Rimi, who later mocked the president as the “White House’s new fool”.

But the incident has been more than a massive PR disaster for the White House: its clumsy meddling in Yemen will inevitably worsen an existing quagmire.

The messy landscape of war

US counter-terrorism operations in Yemen are not new. Neither are foreign interventions, like the disastrous ones that thrived under Obama, whose administration managed to keep the body count from his drone strikes as opaque as possible.

In Yemen, these operations are taking place amid a fully fledged civil war, one searing slightly beneath the mainstream media’s radar. The UN occasionally reminds us of the death count, which has remained at 10,000 since August 2016.

Every botched raid or drone strike serves as a key recruitment tool for AQAP to only gain greater strength

Access and lack of media freedom has severely disrupted reporting on the conflict, which has escalated since a Saudi Arabia-led coalition intervened in March 2015 to restore President Abd Rabbuh Hadi, removed when Houthi rebels took over the capital, Sanaa.

But Trump’s approach has so far been bullish - so bullish, in fact, it made one Yemeni tribal leader wonder if the new president had been watching a lot of Steven Seagal movies.

On Tuesday, it was reported that, in the wake of the Yakla debacle, Yemeni officials withdrew their permission for the US to run Special Operation ground missions against suspected terrorists in the country. A day later, Yemen's foreign minister denied the reports and said that his government wants to rethink US counter-terrorist operations on its territory.But even beyond Yakla, his strategy risks drawing Iran deeper into Yemen’s turmoil.

Overblown proxy label . . .

Reports that the Iranians have supported the Houthi rebels with aid and weapons, and that Hezbollah has also offered support, have led many to label the Yemeni conflict as a proxy war.

But while Saudi Arabia remains very interested in establishing its presence in the region, Iran’s power has been overstated by this narrative.

Certainly, Iran has expressed rhetoric on Yemen, declaring Sanaa the fourth capital under its remit, but the scope of its support has been said to be too limited to shape the battlefield or to consider the Houthis a true proxy for its regional struggle with Saudi Arabia. Many of the factions in the group still do not support Iranian control.

And whatever support Iran may be providing Houthi rebels – whose access to arms, by the way, is not restricted to Iran’s supply - can’t match the extensive military resources being extolled by Saudi’s coalition.

So the idea that Houthis would want Iran’s intervention because they are Zaidis and part of the Shia sect is a false equation. In sum, Iran has limited influence over how Houthis execute this war. Nonetheless, Iran is a useful ally.

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, has support from the US and also the UK and their reasons for maintaining the Sunni government arguably go beyond the need to counter the non-existent Iranian threat. They are more likely aligned to interests in an oil pipeline in Yemen.

But if the conflict in Yemen wasn’t a proxy war before, it could soon become one.

. . . but a real proxy war on the horizon

Obama’s peace efforts in Yemen, which some argued were heading for success, have now collapsed.

Trump is goading Iran with tweets, brash speeches and threats of sanctions. His national security adviser, Michael Flynn, has called the Houthis Iran’s “proxy terrorist group” – something the previous administration explicitly refrained from doing – while White House press secretary Sean Spicer blamed Iran for attacking a US naval ship, something that simply wasn’t true.

On 30 January, the Houthis launched a suicide attack on a Saudi frigate in Red Sea, killing two crew members. Days later, Houthi rebels reported that they fired a Scud missile into Saudi Arabia, which they alleged landed onto a military base near Riyadh. The Houthi attacks onto Saudi’s southern border now pose more of a risk with missiles now reaching inland without interception.

It could also alienate US allies in the Yemen government, as reports of a withdrawal of permission for US ground operations following the Yakla raid suggest.

Could Russia sort out Yemen’s problems to counter US influence? One analyst thinks so. But if the Syrian conflict provides any insight into what help from Moscow looks like, this does not bode well for Yemen.

The real winner: AQAP

Despite the campaign to curb AQAP’s strength, the group has been the one clear profiteer of the conflict’s power vacuum.

Formed in 2009 among fighters who returned to Yemen in the 1990s after battling in Soviet-occupied Afghanistan, AQAP has never gained overwhelming support from the local population, tribal, Sunni or militia. But neither have they been antagonistic, reserving aggression for Western targets instead.

But every botched raid or drone strike serves as a key recruitment tool for AQAP to only gain greater strength. The brutal killing of an eight-year-old Nawar al-Awlaki by the Americans during the 30 January raid is the perfect shop window.

Blurring the lines between AQAP supporters, Sunnis and others against the Houthi rebels has been a tactic that has worked in al-Qaeda’s favour.

AQAP have taken full advantage of the fighting in Yemen – and its resulting problems. Taking over large swathes of territory, particularly on the coastline, they are gaining inroads into Sunni areas, forging local alliances.

Since the raid on 29 January, AQAP have taken back three southern towns in the Abyan province, a former al-Qaeda stronghold that was taken by the Saudi coalition in 2016 after government troops had pulled out over unpaid wages.

The governance and security AQAP provides in those areas are seemingly serving those populations better than any of the other parties. Blurring the lines between AQAP supporters, Sunnis and others against the Houthi rebels has been a tactic that has worked in the group’s favour.

If Donald Trump continues with his current policy - a combination of ill-thought counter-terrorism initiatives, increased backing of Saudi Arabia and the alienation of Iran – one party will clearly continue to profit above all.

- Sophia Akram is a researcher and communications professional with a special interest in human rights particularly across the Middle East and Asia.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Yemeni security forces inspect unexploded ordnance confiscated from al-Qaeda militants in the Lahj province in April 2016 (AFP)

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].