Checkmate in Syria: Erdogan’s gambit with Putin is not paying off

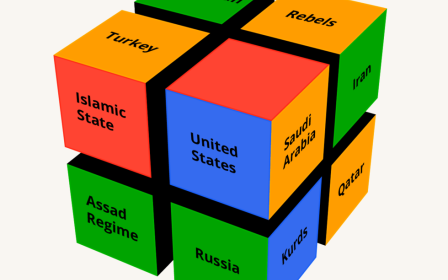

When Turkey reconciled with Russia and offered its regrets for shooting down a jet fighter in November 2015, the move looked like a strategic masterstroke. It cut the US out of the diplomatic and strategic game in Syria and opened the way for a working partnership in that country between Ankara, now with its own military contingent in Syria, and Moscow.

One of the main Turkish motivations for striking up a partnership with Moscow and moving Turkish troops into Syria has been checkmated

Eight months later, things are not turning out like that at all. Turkey’s Syria policy seems to have gone badly awry, leaving Ankara’s forces boxed in. They have achieved little other than the capture of Jarablus and al-Bab, in a northern strip close to its border.

Worse still for Ankara, Russia seems to be protecting the Syrian Kurds from any Turkish moves to end their autonomy. This week, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey expressed his ‘sadness’ at the continuing links of both Russia and the US with the Peoples' Protection Units (YPG) in Syria. His words came after Russian troops were deployed in Afrin, the isolated western-most Syrian Kurdish enclave.

Though Turkey warned it would retaliate against further PYD attacks, the unavoidable assumption has to be that Russia is there to provide a protective umbrella to the autonomous Syrian Kurdish enclave.

Thus one of the main Turkish motivations for striking up a partnership with Moscow and moving Turkish troops into Syria - subduing the break away Syrian Kurdish enclaves - has been checkmated.

Pushed out by a tandem act

There is worse still for Ankara. Instead of Turkey enjoying an implicitly anti-American partnership in Syria with the Russians, Moscow is acting in tandem with Washington.

About two and a half weeks before they moved into Afrin, Russian forces made an even stronger statement by moving into Manbij, the Kurdish-held Arab town in north Syria which religious conservatives in Turkey, including the Turkish offshoot of Ikhwan (Muslim Brotherhood) saw, and indeed still see, as the logical next target for its troops. There, they joined US forces who have since been reinforced.

This development might seem, on the face of it, not unlike what happened in Iraq after 2003 with the appearance of the Kurdish Regional Government

Turkey had bombarded Manbij and other Kurdish areas throughout February, but that option now seems firmly closed. Meanwhile, YPG forces have begun working with American troops to advance on Raqqa, the Islamic State (IS) capital, and Turkey seems to be cut off without a role.

Ankara is thus bitterly complaining that the actions of the US and Russia are helping the Syrian Kurds to ‘pursue their own agenda’. Regardless of their political complexion, everyone in Ankara fears that the real agenda is to create some sort of recognised Kurdish autonomy leading eventually to the formation of a quasi-independent Kurdish state.

This development might seem, on the face of it, not unlike what happened in Iraq after 2003 with the appearance of the Kurdish Regional Government at Erbil.

This was also the by-product of an American intervention. In the case of northern Iraq, common Sunni opposition to the predominantly Shia Iraqi government in Baghdad, and the conservatism of the local Kurdish leadership along with mutual economic interests, enabled Ankara to find a modus vivendi with the Iraqi Kurds.

Similar conditions do not exist in Syria where the Kurdish leadership (and many of the fighters) have close ties with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the Kurdish terror movement inside Turkey which is locked in a brutal conflict with the Turkish armed forces.

Against this background, it is not surprising that other aspects of the Turkish-Russian reconciliation are also proving disappointing. Things are not going smoothly on the trade front where the two countries are trying to restore links severed in 2015. The Russians have proved slow to reactivate purchases of several Turkish agricultural exports, possibly because of quality control issues, and so on 15 March, Turkey introduced a huge retaliatory 130 percent tariff on wheat imports from Russia.

Waning power at the negotiation table

Turkey’s role in the Syrian peace process also seems to have waned. Turkey, Russia and Iran remain the three guarantor powers for the ceasefire in Syria, but when the third round of negotiations was held in the Kazakh capital Astana on 15 March, the Syrian opposition whom Turkey backs stayed away. Though the final communique at Astana suggested that the talks had been constructive and useful, Syria blamed Turkey for the opposition boycott.

Curiously, the Russians do not seem to be trying to cement their friendship with Turkey into a close partnership aimed at detaching it from the West

Turkey’s allies, the various factions in the Free Syria Army, are discontented with a settlement framework which is highly unfavourable to them. But since they have failed to do what the YPG has so strikingly done, i.e. coalesce into a strong modern fighting army, the groups inside the FSA are getting little or no international attention.

That might change if the surprise offensive they launched against Damascus on 20 March succeeds in shifting the military balance inside the country, but a large-scale renewal of conflict would probably drag Turkey, as their main sponsor, into a confrontation with Russia.

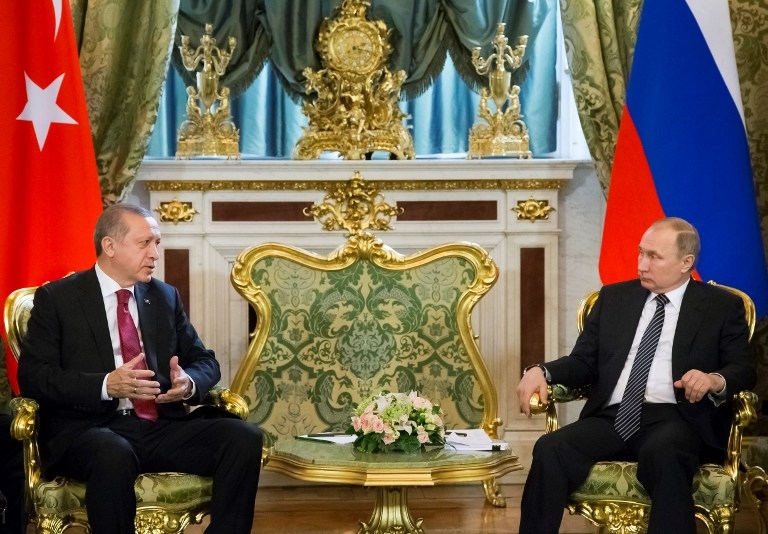

That seems to be something Ankara is determined to avoid. Though its contacts with the Russians (including the recent summit in Moscow by Presidents Erdogan and Putin) have been unrewarding, there has been almost no public criticism until now and the official narrative has been one of growing cooperation – a version increasingly challenged by the facts on the ground.

Is this because of a secret US-Russian understanding on global zones of influence? Or does it simply reflect a Russian sense that, while Turkey is at loggerheads with the EU and furious over American backing for the YPG, a soft line towards Moscow is its only option?

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant, and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics, and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Russian President Vladimir Putin (R) speaks with Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (R) ahead of their meeting in the Kremlin in Moscow, on 10 March 2017 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].