Egypt is no longer the heart of the Arab world

The status of a country is not determined, as some historians would have us believe, by its history alone, nor just by its geography, nor indeed by its political will. The role of countries is fashioned by the interaction of geography, history, politics and resources together.

It is through a combination of these forces that Egypt's role was born and developed in the lives of Arabs during the 20th century, in the aftermath of the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

Egypt's soft power, if you could call it that, emerged in the second half of the 19th century. However, one should not exaggerate it. Egypt fell to British colonialists in 1882.

Working on the back of the modernisation project undertaken by Khedive Ismail, the British endeavoured to create a relatively liberal climate, which attracted a number of educated Christians in the Orient along with an equal number of reformist Salafist scholars.

The role played by all of these elements in Egyptian, and more generally in the Arab culture, exaggerated the importance of Cairo in the 19th and early 20th century Cairo. But the truth is that, until the First World War, Istanbul continued to be the centre of culture and politics in the region.

First there was Istanbul

It was to Istanbul that hundreds of Arab and Muslim activists headed, including many Egyptians. It was in Istanbul that decisions and key political currents were formed. And it was from Istanbul that these individuals went out to start the struggle against foreign hegemony.

Until the First World War, Istanbul continued to be the centre of culture and politics in the region

If Damascus was the first cradle of the Arab movement, the more important streams of Arabism sprung from within the circles of Arab students and educated Arabs who lived in the capital of the sultanate.

Istanbul's role came to an end with the defeat of the Ottomans and the birth of the Turkish Republic, whose first act was to isolate and disengage itself from the Arab world.

From then on, Arabs embarked on a tough journey in search of a new frame of reference for their identity, as well as for liberation from foreign hegemony and deliverance from partition imposed on them from afar.

Rise of Egypt

Not only did the Arab movement expand its horizons throughout the 1920s and the 1930s, but it also achieved significant steps in the fields of Egyptian culture and politics.

Despite the political jealousy seen so often in Iraq, Syria and Saudi Arabia, Arabs as a whole saw in Egypt their most important centre of gravity

This development was accompanied by the birth of a noticeable level of awareness, particularly among the Egyptian elite, commensurate with the size and position of the country and with its potential role.

With much support from secular circles in his country, King Fuad tried in the 1920s to inherit the post of caliph after the Caliphate was annulled by the republic in Turkey. King Farouk surrounded himself with Egyptians, both Arabists and Islamists, who imagined that Egypt could lead the entire Arab world.

There is no doubt that the birth of the Palestine question, and the role played by Egypt, or the role Egypt had to play, in support of the Palestinians helped to elevate the Arabs' view of Egypt and the Egyptians' view of their own country.

Maker of Arab conscience

During the post-1952 era, Arabism became the official frame of reference for the Egyptian republic. The Arabist trend, which had been controversial during the period between the two world wars, transformed into well-respected policies, drawn with strategic considerations – economic, political and cultural – even if at times Egypt would seem to be the underdog.

This is how Egypt became the centre of Arab culture and a reference for policies. Starting in the late 1930s, Egypt led the Arab world's struggle for Palestine and hoisted the banner of Arab unity. It became the home of the Arab League, supported Arab liberation movements' struggle for independence and waged war after war in order to assert the position of the emerging Arabs on the global scene.

Not many Arabs paid much attention to the roles played by Baghdad and Aleppo in developing modern Arabic music because Egypt, and only Egypt, had become the centre whose role was recognised by the Arabs as essential in shaping their musical taste.

In addition to that, Egypt continued to host the bulk of the Arab cinema industry. So much so that the Egyptian dialect became a sort of synonym for Arabic proper. For decades, the Egyptian University - now known at Cairo University - was a mecca for Arabs ambitious to receive a modern education.

Higher education institutions that soon sprang up in the capitals of the recently independent Arab countries, one after the other, followed the example of the Egyptian University and emulated it. This was not confined to modern education.

The status of Al-Azhar as a bastion of Islamic sciences did not waver, neither with the spread of competitive Islamic education centres nor as a result of the disconcerting clash between the republican regime and the Muslim Brotherhood.

In short, Egypt not only became the beating heart of the Arabs but also the maker of their conscience and their modern soul.

Imprinted in memory

It was not strange, therefore, that Egypt's position and role, which lasted for more than six decades, should acquire so much weight in the memories of Arabs.

And not only in Arab collective memory but also in the memory of the biggest segment of non-Arab observers and specialists who continue to conceive of Egypt as the standard of Arab existence and the index for the Arab future.

The majority of Arab politicians, activists and campaigners imagine that crises within the Arab world have been magnified by Egypt's absence and believe that Arabs will find no way out of their predicament until Egypt rises again. The Arabs' path toward a better future, they believe, is conditional upon Egypt's resumption of its responsibilities as leader of the entire Arab world.

Yet, reality tells the Arabs that they must today give less weight to that memory and free themselves from their captivity. This is not because Egypt has lost its significance, position or size, but because Egypt is not on its way to recovery or revival. It does not seem likely that it is returning any time soon to assume the leadership of anything.

Total wreck

It must be recognised that Egypt is no longer the fountain of Arab conscience, nor any longer is it the maker of Arab culture. Egyptian education fell apart quite some time ago, and Egyptian arts are in a state of decay, while the Egyptian media are a source of shame.

Egypt requires a total and radical dismantlement of the current political, social and economic structures for a new state to be rebuilt from scratch

Egypt suffers from an economic crisis that is likely to last for many more decades and has suffered a major collapse in most if not all its service sectors from transport to health.

Although state institutions are not in particularly good shape in any Arab country, the Egyptian state started declining as early as the 1960s and is a total wreck today. For all its size and history, Egypt has become captive to - and under the total influence of - a much smaller and much younger state in the Arabian Gulf, Saudi Arabia.

However, such an option does not seem to exist in the reckoning of the ruling class and its cultural milieu, nor does it exist in the reckoning of the opposition’s forces and currents.

Even if such an option becomes attainable, it would take decades before Egypt is able to regain some of the role and some of the influence it enjoyed in the modern history of the Arabs.

In other words, the Arabs must stop waiting for Egypt and rid themselves of this irrational nostalgia for its past role. They need to start searching for their future regardless of whether they are able to lend a helping hand or not.

- Basheer Nafi is a senior research fellow at the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

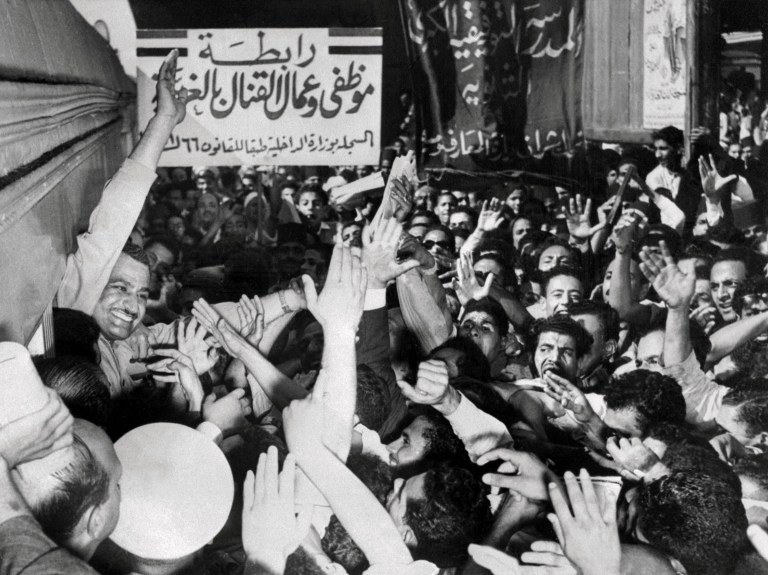

Photo: A crowd greets Colonel Gamal Abdel Nasser as he enters Cairo station on 29 October 1954 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].