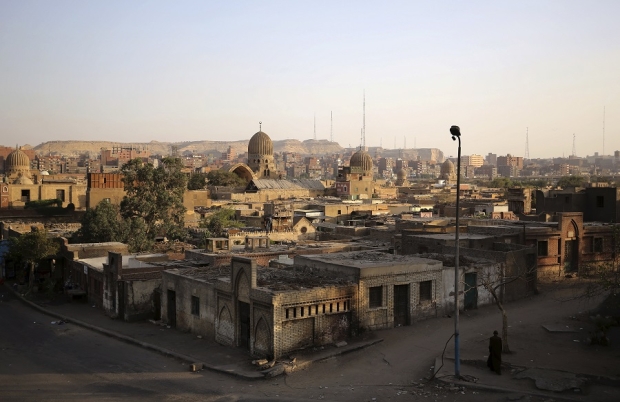

Meet the people living in graveyards in Egypt

CAIRO - A family huddles around a TV, watching a Bollywood movie, occasionally bursting into laughter at an especially funny scene.

Outside a convoy arrives, carrying a small dark blue coffin. Among the mourners are women, wailing and sobbing at the loss of the dead child.

Nearby, a crowd watch the match between Ismaily and Al-Ahly, Egypt's leading club, on a TV attached to a wall, greeting each Ahly goal with cheers and applause. The child’s funeral continues.

"At the beginning it seemed very hard and difficult to live here. After some time, you get accustomed to it. It becomes normal, " says Sabreen, a mother of three.

Sometimes I feel we are both dead, but we are still not buried

- Sabreen, mother

"Sometimes I feel we are both dead, but we are still not buried," she adds, referring to her husband, Sayed al-Araby. Al-Araby was born in the graveyards, and the 67-year-old fears that his children will spend their lives among the dead, following in the footsteps of their father and grandfather. "It is a hard and miserable life that I don’t want my son to inherit too,” al-Araby says, pointing to his humble possessions. The place he calls home is crowded with his wife, son and two daughters who returned home after getting divorced.

"We live here generation after generation, with no chance of getting out."

Before the 13-year old left for his job at a popular foul (fava beans) street food cart where he tries to help his struggling family by making 30 EGP ($1.68) a day, he said:

We live here generation after generation, with no chance of getting out

- Ahmed Sayed

"Many people come and take photos and statements to promote our issue, and then nothing happens. Even you, you will not help us," he adds, referring to MEE's correspondent.

In 1950, al-Araby's father, Abdel Hameed, moved to Cairo with his wife from his village in Giza - 35 km south of Cairo - in search of a job. Failing to afford even a small apartment for his family, he moved to a tomb owned by a wealthy family, in a cemetary near Al-Azhar mosque, which dates back to around 1,000 years.

Some of the inhabitants work as caretakers, digging and tending to the graves, while others work as vendors, offering different services.

The tomb, which is roughly 200 square metres, has a small burial room. Egyptian families with enough money usually purchase tombs that include at least one room, where they honour the dead.

They are meant to provide family members with a space to rest and spend the day, when visiting their deceased relatives at the weekend or during religious occasions.

Scattered in a small room are a few pieces of furniture and signs of life. The family makes do with one squalid bed, two small couches that also serve as beds, an ailing washing machine and a small TV.

It is a hard and miserable life that I don’t want my son to inherit too

- Sayed al-Araby, shoemaker

Food preparation is kept simple with the use of a small and decrepit cooker, with their diet mostly consisting of rice, pasta, potatoes and legumes. They can rarely afford to buy meat or chicken.

"We eat day by day and we never have extra food, so we don’t need a refrigerator," he says.

When al-Araby and Sabreen first met, she was also living in the graveyard with her parents.

In 2008, Egypt's national statistics agency said that 1.5 million people were living in Cairo's graveyards alone, but this figure has not been updated since then. In September 2017, the Central Agency for Public Mobilisation and Statistics (CAPMAS) stated that there is no precise figure for those living in Egypt's graveyards. In a country with a booming population of over 90 million, more than 20 million live in the capital Cairo.

Outside of the tomb but close to the burial room, a hole in the ground that is surrounded with wooden bars acts as their bathroom. A metal canister is stationed there to help them with washing up and cleaning.

According to official statistics issued in 2017, 40,000 families live without proper bathroom facilities.

“This how we live in 2017. No access to fresh water or electricity or any of our basic needs,” he says in disappointment.

As a shoemaker, al-Araby does not have a fixed income and he says the demand for his trade is very low.

Adding to life's burdens is the fact that Sabreen suffers from heart disease and al-Sayed cannot afford medication, which costs around 250 EGP ($14) a month. Luckily, a local charity offered to pay for her treatment and even financed a heart operation for her.

'I sleep with my eyes open'

The neighbouring tomb is home to 63-year-old street vendor Younis Ibrahim, who sells anything worth buying, including shirts and shoes.

The father of eight has attempted to block holes in the tomb's main door by using wooden bars and plastic bags. The decaying entrance lets in cold air when the family tries to sleep at night.

All that I want is anything with a door that can be closed on me and my family

- Younis Ibrahim, street vendor

“All that I want is anything with a door that can be closed on me and my family. I sleep with my eyes open fearing thugs at night,” he says.

Ibrahim points out that the fence surrounding the tomb is low, allowing access to anyone who jumps over it.

In 2000, Younes and his family were evicted from their house in the Sayeda Zeinab neighbourhood after failing to pay their monthly rent of 250 EGP ($14) for 16 months. Today, they live in a small room that does not exceed seven square metres.

“I have eight sons and daughters. My salary didn't exceed 500 EGP ($28) at that time. I failed to pay the rent and most of the daily expenses,” he says.

When he and his family moved there in 2000, they were paying the caretaker 40 EGP ($2.24) a month. Since then, it has increased to 100 EGP ($5.60). Some of the caretakers in the area illegally rent out the tombs to residents.

In 2016, CAPMAS announced that about 27.8 percent of the Egyptian population is living below the poverty line, with an annual income of less than 6,000 EGP ($340).

Daily prices have surged since Egypt floated its currency in November 2016 and the Egyptian pound plunged against the dollar.

I lived my entire life in this tomb, got married and had my children and now I am going to die here

- Sayed al-Araby, shoemaker

Ironically, Younes is standing in front of a poster that reads: “The people's wish is our command." It is part of a campaign launched by local talk show host Amr Adib to encourage discounts on basic products.

“Everything is still expensive,” he laughs. Younes dreams of a flat that houses and protects his family. For him, it could be anywhere.

“But the issue is very difficult. How could I get a down payment? If I have 1000 EGP ($56), I would buy food for my family."

On the other side of Cairo's main street, Salah Salem, is the El-Imam El Shafei graveyard. There, Mahmoud El Saedy, 45, shares a tomb which has two rooms with another family. The space is relatively big.

The father of seven has lived there since 2005. At the time, his monthly rent was 60 EGP ($3.36), but today rent stands at 120 EGP ($7).

“If I could afford to pay a rent, I wouldn’t live with the dead," he says. "At the beginning, it was hard. I couldn’t even sleep. I'm living with dead people. Later I realised we are all dead."

'I lived my entire life in this tomb'

Cairo Governorate spokesman Khaled Mostafa told MEE that the “government considers the issue of slum area residents a top priority”.

Refusing to give a precise figure for the number of people living in Egypt's graveyards, Mostafa refers more generally to projects which aim to move inhabitants in slum areas to regular housing such as “Al-Asmarat" in southern Cairo or in "Ghait El Anab" in western Alexandria.

It seems that the government has forgotten about these people for decades

- Medhat, NGO

Medhat, who only gives his first name amid fears for his safety, is an activist who runs an NGO that offers basic needs like food, medicine and other serivces to graveyard inhabitants in the Al Shafei area. He feels the government pays no attention to this sector of Egyptian society. “It seems that the government has forgotten about these people for decades," he says.

Successive governments in Egypt have promised development and change, but it has never been delivered.

Local media commonly report that graveyards are strongholds for criminals and drug dealers, and are used as hideouts.

"These people only need to be acknowledged and recognised as normal people with the same rights,” says Medhat.

Al-Araby adds: “I lived my entire life in this tomb, got married and had my children, and now I am going to die here."

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].