Algeria's Berber new year aims to show state's approval for 'invented tradition'

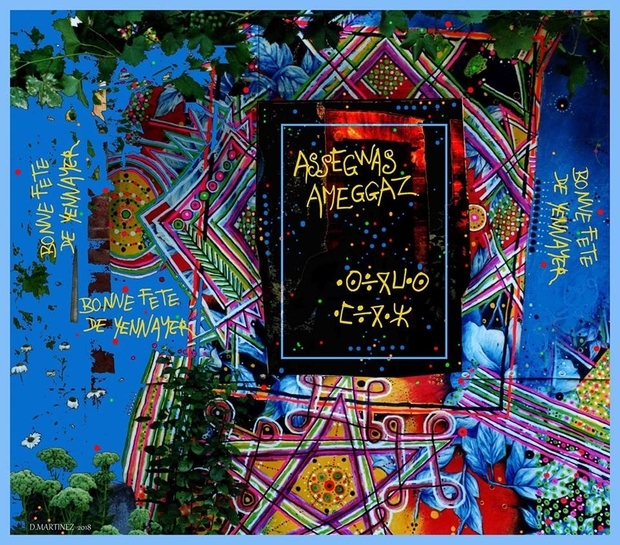

On 27 December, Algerian President Abdelaziz Bouteflika announced, at the Council of Ministers, his decision to establish Yennayer, the first month of the Berber year, as a bank holiday, as of 12 January 2018. The list of bank holidays in Algeria therefore now includes a celebration that can most likely be traced back to the Roman occupation of North Africa, if not further.

Yennayer is the first day of the year in the North African agricultural calendar, modelled on the "Julian" calendar. Its new year starts a few days after new year's day in the Gregorian calendar, itself an adjustment to the Julian version and in use throughout much of the world.

The lag between the two calendars has been growing since the 16th century. It stands now at 13 days, meaning that Yennayer should be celebrated this year on 14 January.

By declaring that 12 January is a paid day off work, the government actually does not follow the North African agricultural calendar. It makes official a recent tradition that celebrates Yennayer on a fixed date, on 12 January, as if the difference between this calendar and the official state's calendar could be stopped forever.

The government officialises a recent tradition that celebrates Yennayer on a fixed date, on 12 January, as if the difference between this calendar and the official state's calendar could be stopped forever

The word Yennayer, which designates the month of the same name and its first day, is often asserted to be an authentic Amazigh (Berber) word. It derives, however, from the Latin Ianuarius, which means "January". The argument that it is a Berber word made of yen (one) and ayer (month) has more to do with an "identity" etymology than science.

Firstly, if we recognise this etymology, all the first days of the month should be called Yennayer. Secondly, the month of January has in other places, such as Egypt, a similar name - Yanayer.

Amazigh new year?

In its comments on the presidential decision, the Algerian press, including the Algerian Press Service (APS, the official press agency), have called Yennayer the "Amazigh new year day".

The official statement of the Council of Minister on 27 December does not do so, officially calling it "Berber". This - despite the fact it is celebrated in such Berber areas as Tlemcen and Tenes, as well as in the northwestern Haute Kabylie area and in the Aures mountains - would reduce its "inclusive" character and open a breach in what a minister of the Ouyahia government has called "the identity unity of the Algerian people".

In fact, the calendar whose year opens with Yennayer remains in use, though on a very small scale, in other countries. It was used in Algeria by Berber and Arabic speakers but, with the modernisation of agricultural work, it was gradually abandoned by both.

Still, the names of some months of this disappearing calendar survive in a rather curious fashion in the Arab edition of the solemn JORA, the official newspaper of the Algerian Republic, in which August is called Ghoucht, June Younyoun and July Youlyou. These names are also used in other official calendars in the Near East, demonstrating that the ancient world was less culturally partitioned than our contemporary "village".

The fact that a tradition does not trace back to antiquity does not mean that it is necessarily unanchored in society

What Kabyles from Haute Kabylie call Thabbourth useggwas, meaning the door of the year, was celebrated in Algeria by a series of rituals performing a magical function generating a lot of festivities. The feasts were supposed to ease the concerns of agriculturalists, whose harvests depended on a versatile sky. They aimed at averting the threat of famine, which was an ever-present concern before the arrival of petrodollars.

These developments in the etymology of Yennayer and on its magic-agricultural origins would not be of interest if they did not demonstrate that celebrating it on a fixed date, the 12th of January, as the "Amazigh new year's day," is an invented tradition, to use the term coined by the British historians Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger.

It has only a distant relationship with the initial symbolism of Thabbourth useggwas, the popular North African celebration.

However, the fact that a tradition does not trace back to antiquity does not mean that it is necessarily unanchored in society, and Algerians are not the only ones who are passing off contemporary cultural traditions as very ancient ones.

Even though the celebration of Yennayer under the name of "Amazigh new year" is a recent phenomenon, and though it is not a popular agricultural celebration, it is in a way more grounded in the North African culture than another invented tradition. The calendar of the Berber Academy in the 1960s fixed "year one" of its calendar on the accession to the Egyptian throne of Shosenq in the 10th century BC. Shoshenq was a general of ancient Libyan descent (proto-Berber) of the Egyptian army, in a possible political-magical revenge on Nasser and Nasserism.

The decrease of Arabist circles within the regime

The decision to make Yennayer a bank holiday was announced at the same time as an instruction given by President Bouteflika to the government "to spare no effort to generalise the teaching and the use of Tamazight" (the name given to a standard Berber language, which is under development) and to "hasten the preparation of the draft organic law to create an Algerian Academy of the Amazigh language".

These measures mark a new step in the coerced but real easing of the regime's attitude towards the cultural and linguistic issues of the Berbers. They confirm the weakening of the Arabist circles within the regime, seen in the diplomatic withdrawal of Algeria within the Arab region, where Arabism undoubtedly is being confronted by local patriotism (for example in Egypt, Iraq and elsewhere).

If he were alive today, the founder of the Berber Academy in 1966, Mohand Arab Bessaoud, would be very surprised by Bouteflika's creation of an "Algerian Academy of the Amazigh language," Bouteflika being the companion of Algeria's second president, Houari Boumediene, whose Arabism had a big part in the development of Berberism.

This easing of the official attitude towards Berberism, which has gained pace over the past two years, started in 1995 - following a year of a boycott of schools in the northwestern coastal region of Kabylie - with the launch of the teaching of Berber languages. As was surely noticed in high circles, this initiative did not transform Berber speakers into aliens, dangerous to the identity purity of their Arabic-speaking compatriots.

It continued in 2002, within the context of popular demonstrations against police crackdowns in Kabylie. These demonstrations ended bloodily. The easing materialised further in 2016, with the officialisation of Tamazight, alongside Arabic.

The regime versus Kabylie independence seekers

As we can see, Kabylie is the main place where the future of cultural and linguistic demands of Berber-speaking Algerians was decided. Even the establishment of Yennayer as a bank holiday was claimed in Kabylie more than anywhere else, despite the fact that this region - before the development of the new movement of Berber culture - used to celebrate it less than other regions, as shown by the Berber Encyclopedia.

The recent measures for the Berber culture and language are undoubtedly aimed at gathering more votes before the presidential elections of 2019. We do not know if President Bouteflika, who has been ill for the past 13 years, will be a candidate or not for a fifth term.

In Kabylie, the influence of traditional political parties (the Socialist Forces Front and the Rally for Culture and Democracy) is decreasing, which deprives the regime of "reasonable" interlocutors and opens the way for the Movement for the Autonomy of Kabylie (MAK).

This movement has not disappeared despite its divisions, old and new. Moreover, its project for autonomy, which it defended before opting for an outright independence project, is gaining new followers among the Kabylie political elites. This is shown by the recent creation of a "Rally for Kabylie," demanding "large autonomy" for the region within the Algerian state - a bit like what the MAK demanded in its early stages.

As we know, by the very fact that this movement has changed since its foundation, nothing prevents autonomism in a specific local and regional context from evolving into a struggle for independence.

- Yassine Temlali is a journalist, translator and researcher in history. He has studied French literature and linguistics in Constantine and Algiers. He is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Marseilles/Aix-en-Provence in contemporary Algerian history. He works with a few publications in Algeria and abroad. He has published La genèse de la Kabylie. Aux origines de l’affirmation berbère en Algérie 1830-1962 (Algiers : Barzakh, 2015/Paris : La Découverte 2016) and Algérie, Chroniques ciné-littéraires de deux guerres (Alger : Barzakh, 2011). He has also worked on a few collective publications, including L’histoire de l’Algérie à la période coloniale : 1830-1962 (Algiers : Barzakh/Paris : La Découverte, 2012).

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Since his first election campaign, Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the president, is seen in Tizi Ouzou, with his sister (on the right) and the mother of Lounès Matoub, a singer who was assassinated on 25 June 1999. This operation of reconciliation around the “Matoub symbol" failed, and, in 2001, more than 100 demonstrators were shot dead during the Black spring (AFP).

This article was originally published in French on Middle East Eye French.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].