The farcical process of Egypt's elections

In March 2011, I was in the border town of Salloum, at the land crossing from Egypt into Libya, ready to cast my vote in the referendum on constitutional amendments tailored by the then-ruling military council and their post-revolution partners from Egypt's Islamist spectrum, led by the Muslim Brotherhood.

Standing in a line of tribal, turban-wielding men, I certainly stood out. I was the recipient of threatening looks maybe because people assumed that I will vote no to the amendments described - at the time - by some religious leaders as a necessity to preserve Egypt's Islamic identity.

Despite the violations that marred this process and its effects on post-2011 Egypt, it remained a free and fair referendum, reflecting the power of various Egyptian political and revolutionary youth factions. It was a democratic process. My Salloum experience was the first, followed by the November 2011 parliamentary elections and the two rounds of presidential elections in mid-2012.

Past versus present

In spite of the instability and gradual crushing of the popular demands that once echoed on Tahrir Square, those elections continued to be the proud moments that saw - for the first time in the history of Egypt - independent, liberal youth under the dome of a parliament gripped for decades by dictators and their cronies.

The heated political debates I once witnessed in 2011 and 2012 outside of polling stations between representatives of different parties and even between voters are now considered a reckless risk that would likely lead to detention and an unknown fate

It saw defected Muslim Brotherhood figure Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh campaign against his life-long partners, Mohamed Morsi and Khairat el-Shater; and it saw Hamdeen Sabahi fiercely compete under a leftist banner in the face of Islamist slogans, while Khaled Ali marched with the backing of labour unions he continually defended in the courts of law.

Those were elections, free and fair despite the violations. Those were democratic events into which I walked with my notebooks and cameras, freely conducted interviews with voters and monitors, wrote my coverage, then proudly returned to witness the ballot count and ink my signature and national ID number on the "witness form".

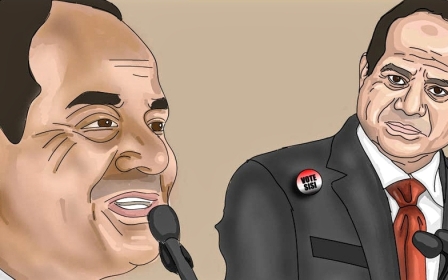

Those elections have nothing in common with what the current military ruler of Egypt, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, is trying to promote as elections.

In a recent television interview, Sisi appeared in casual attire, answering the questions of one prominent Egyptian cinema figure, Sandra Nashaat. "I wish there were 10 [presidential] candidates," Sisi said during his appearance, only a few days before the vote, which has been described by observers and commentators inside Egypt and across the world as a "farce".

Crushing of political rivals

What Sisi failed to refer to, and of course Nashaat would have never dared to mention, was Ahmed Shafiq, Sisi's long-time colleague under Hosni Mubarak, who was deported from the United Arab Emirates to Cairo in the most scandalous manner after announcing his wish to run for the presidency.

Nor did they mention Sami Annan, Egypt's longest-standing military chief of staff and Sisi's former commander, imprisoned in an unknown location because of his will to run for the presidency.

The list goes on, including Khaled Ali, the prominent lawyer whose campaign members were hunted by Sisi's security until he withdrew his candidacy, and Aboul Fotouh, who was thrown in prison over a television interview.

The heated political debates I once witnessed in 2011 and 2012 outside of polling stations between representatives of different parties and even between voters are now considered a reckless risk that would likely lead to detention and an unknown fate.

Military trial, forced disappearance, torture and eventual charges of funding, joining and running a terrorist cell, are all among the many grim scenarios ordinary Egyptians are threatened with every day.

Looking forward

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of voters are stranded in North Sinai in the name of another theatrical stunt dubbed the "Sinai 2018" military operation, also ushered in by Sisi weeks before the election in an attempt to regain some of his dwindling popularity.

As I write this, civilians in North Sinai celebrate if they manage to get a litre of milk and some tomatoes; cancer patients must be permitted by the military to travel outside of the blockaded peninsula to receive chemotherapy; and politicians and community figures beg the authorities to allow more food supplies into local markets.

When my fellow Egyptians stood up for their dignity and God-given rights in January 2011, inspiring the world and calling for bread, freedom, social justice and an end to death under torture in the dungeons of Mubarak's state security, they proved that three decades of iron-fisted dictatorship had not killed their civilized and proud souls, despite drowning them in poverty, illiteracy and injustice.

Egyptians might seem helpless today, as their oppressors celebrate and look forward to another term in power - but that doesn't and won't change the fact that today's polling stations, see-through boxes and permanent ink are nothing but a waste of national resources.

Egyptians deserve democracy and are capable of building and sustaining a democratic system. If today's farce is considered to be a democratic process, then let's at least be honest, save the world our lengthy debates and replay Omar Suleiman's slogan: "Egyptians aren't ready for democracy yet."

- Mohannad Sabry is an Egyptian journalist, expert on security and the Sinai Peninsula, and author of Sinai: Egypt's Linchpin, Gaza's Lifeline, Israel's Nightmare. Sabry has been living in exile since the release of his book in November 2015 and its quick ban in Egypt soon after publication. Sabry was named a finalist of the 2011 Livingston Award for International Reporting, and was among PBS Frontline's team nominated to the Emmy Award for News and Documentary for their 2013 show "Egypt in Crisis".

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Egyptian women gather outside a polling station on the first day of voting in the Egyptian presidential election in the northern port city of Alexandria on 26 March 2018 (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].