Falling lira pushes Turkey towards uncharted territory

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan says his country is at war and will not lose. The “war” he is referencing is over the Turkish lira, which has plummeted this week.

A year ago, there were 3.5 liras to the US dollar. A week ago, it had slipped to five. By noon Friday, it had fallen again, hovering around 6.15. The Financial Times called it “a breathtaking tumble”.

Turkey has had this sort of experience - a disastrous currency collapse shrinking its economy and impoverishing its citizens - several times before, most recently in February 2001. In the past, the country has turned to conventional solutions, such as bailout loans and economic reforms through the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which has provided tens of billions in assistance. Today, however, this does not appear to be on the cards, amid growing divisions between Turkey and the US.

US missionary jailed

All decisions about the way forward rest with Erdogan, and thus far, he seems undaunted. On Friday morning, he told his followers in the remote eastern province of Bayburt that “the dollar or anything like it will not be able to stop us going on our way”. Those words will further alarm many investors, suggesting that Turkey will neither impose a conventional economic programme to protect its currency nor find a way to come to terms with the US over a tangle of issues that have brought them to loggerheads - chiefly, the jailing of US missionary Andrew Brunson on terrorism charges.

In Washington, a Turkish delegation has reportedly been trying to thrash out a deal to restore working relations, but it has been unable comply with US demands, including the release of Brunson and other prisoners.

In Washington, where Turkey seems to have lost its friends and faces a passionate anti-Erdogan lobby of which the Gulenists are an important part, there may be wishful thinking that an economic collapse could sweep him from power

The US may also be stuck on Turkish demands to waive or minimise a treasury fine on Halkbank, a Turkish state bank involved in a court case over violating US sanctions on Iran. Its deputy general manager was sentenced to 32 months in prison. Turkey fears the fine on Halkbank - a small player by global standards - could follow the precedent of the hefty US treasury fines levied on German and Swiss banks for sanctions-busting.

Has the moment finally arrived when political and economic ties between Turkey and the US snap, ending what was a very close partnership dating back to the late 1940s? Possibly. But neither Erdogan nor Trump planned this - even though some parts of the AKP media have long seen the US as a deadly enemy. A month ago at the NATO summit in Brussels, the two leaders chatted amicably, and Trump afterwards spoke appreciatively of Erdogan.

The collision results from inflexibility over two policies, the first being Erdogan’s firm belief (against conventional economic theory) that high interest rates cause, rather than curb, inflation. This has caused the decline of the Turkish lira over the last three years. The second is the Turkish government's unwillingness to release Brunson after nearly two years in prison, merely to keep him under house arrest.

An intolerable slight

Here, the Americans might have moved too soon, not realising that in Turkey, house arrest would almost certainly lead to dropping charges. On 26 July, Trump and Vice President Mike Pence threatened sanctions if Brunson was not instantly released. In Turkey, that was taken as an intolerable slight to which leaders could not bow.

If the two sides remain unable to reach a compromise - which looks much more likely now than it did a few days ago - the cost will be very high for both. The US will have finally lost a large and strategically positioned NATO ally. But Turkey would undoubtedly sustain much more damage, with its large companies and banks struggling to pay for borrowing in foreign currency and short-term money - vital to its economy - being scared away. The consequences for millions of Turkish families were very harsh in 2001; they may be even harsher this time.

In Washington, where Turkey seems to have lost its friends and faces a passionate anti-Erdogan lobby of which the Gulenists are an important part, there may be wishful thinking that an economic collapse could sweep him from power. But that seems to underestimate both Erdogan's following and his strong hold on power under the new constitution.

“A US-induced crisis in Turkey will create a new martyr in the region, with far-reaching consequences which American congressmen and President Trump do not foresee,” Bulent Gultekin, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania and the former Turkish Central Bank governor, told MEE. Gultekin hopes that some sort of compromise between Turkey and the US can be reached, enabling Erdogan to have an “honourable exit” and come up with a substitute for the IMF stabilisation programmes of previous crises.

Reform programme

Such a stabilisation project would have to involve not just a sharp increase in interest rates, but also a full comprehensive programme of reforms, and - what would probably be a very bitter pill - the shelving of many of Erdogan’s expansive infrastructural and defence industry projects, 400 of which were unveiled only a few days ago. And of course, Brunson and the other detainees, including local staff of the US diplomatic mission and various persons thought in some cases to be Gulenist Turkish-Americans, would have to be released.

Nothing like that seems to be on the cards as yet, but it may come. Meanwhile, millions of Turks can do little but woefully check the latest dollar/lira parity. If compromise doesn’t come, Turkey, a country of 80 million people, and the West will find themselves in uncharted territory whose only recent precedent might be the US-Venezuela split.

- David Barchard has worked in Turkey as a journalist, consultant and university teacher. He writes regularly on Turkish society, politics and history, and is currently finishing a book on the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

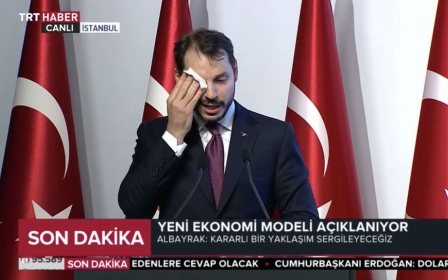

Photo: The Turkish lira has suffered a 'breathtaking tumble' this week (AFP)

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].