'Tints of Resilience': Syrian and Lebanese artists confront grief and loss

LONDON - When Syrian artist Anas Albraehe lost his mother to cancer in 2013, he entered such an intense period of grief and mourning that he could not even bear the sight of her photograph.

In the depths of his pain, which was compounded by a brutal civil war, he left Al-Sweida, his hometown in Syria, the following year to start a new life in Beirut and try to come to terms with the debilitating loss.

I needed to confront her death, so I started drawing what I’d been running from

- Anas Albraehe, artist

“I used to escape all memories of her and all photographs of her because remembering her would stir within me intense emotions,” Albraehe told Middle East Eye from Beirut. “I needed to confront her death, so I started drawing what I’d been running from, incorporating art therapy into my work and dealing with my grief artistically.”

The experience proved transformative. Albraehe went on to earn a master’s degree in art therapy from the Lebanese University in 2014 so he could immerse himself in the discipline and its mental health benefits.

“Art can help you heal from tragedy and confront your past, no matter how painful it is,” Albraehe said. “Anyone can be an artist.”

Neighbour of the Moon, one of the series in the exhibition, depicts Albraehe imagining his mother sleeping on a cloud while an older version of the woman dozes off on a chair. Albraehe said that as a toddler he’d watch his mother knit, creating “colourful threads of memories” and inspiring him to become an artist. “She looks at me from the heavens, while I look at her through my memories, and we’re connected by a knitting thread,” he said of the painting.

The exhibition showcases the art of 11 Syrian and Lebanese artists who have each experienced some form of war, displacement, loss and a search for identity.

A weapon against one’s demons

Partly supported by the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, the display of work makes the argument that art can be wielded as a weapon against one’s demons. The exhibit invites the public to “explore creative ways of dealing with their own difficulties” by offering a series of events including a live interactive calligraphy performance, an art-making and art therapy seminar, and an art workshop.

Scientific studies have shown that the arts can serve as a potent therapeutic mechanism whose ripple effects have the potential to positively impact mental health and even the management of pain. Some have posited that the playful, childlike nature of creative expression can bolster the resilience of those suffering from mental health disorders, suggesting psychotherapists incorporate the practice into treatment plans.Art can help you heal from tragedy and confront your past, no matter how painful it is

- Anas Albraehe, artist

A February 2018 paper published in The Arts in Psychotherapy found the results of an art therapy study conducted on 195 patients were overwhelmingly positive, with participants experiencing improvements in pain, mood, and anxiety, irrespective of diagnosis or age.

“Tints of Resilience" was born of “a strong belief in the necessity of transmitting the voices of Middle Eastern communities through the honest lens and immediate impact of artistic expression,” Rania Mneimneh, a Lebanese artist who curated and participated in the exhibit, told Middle East Eye.

The artist, 32, has also worked closely with blind and visually challenged children, as well as Syrian children in refugee camps who she encouraged to explore “the sense of both self and others” by clay-making and jointly painting a mural that told “stories of friendship”.

“Such projects shed light on the positive influence of art in times of hardship for children and adults,” Mneimneh said.

In one of those canvases, by Abdel Hadi and Fadel, two refugee children from a refugee camp in Lebanon's Bekaa Valley, stars and planets light up the sky. In another, Baraa and Nour, two girls from the same camp, evoke happier times, having painted a girl in a floral dress wearing new ballerina shoes.

Rays of Hope

Safia's Sea, a story written by Syrian author Zeina Kanawati, was adapted into an illustration for “Tints of Resilience” by Syrian artist Dima Nachawi. In the story and illustration, a deaf and mute girl knits a scarf as a concerned-looking owl perches atop the branches of a red tree.

The owl gives Safia the knitting needle and the yarn to distract her from a war whose tentacles had spread as far as the bottom of the ocean, Nachawi explained. While framed as a fable for children, the themes of Safia's Sea are geared towards adults, the artist said.

The message behind the illustration is that “there are rays of hope in the middle of a sea of darkness,” Nachawi said. You could say Safia herself was engaging in art therapy, as was Nachawi, while she painted her.

Children have to see that they are the hero of themselves

- Diala Brisly, artist

Nachawi’s work comes across as intricately layered, like a Russian doll filled with fairy tales. Her art is a form of “resistance,” she says, and it has helped her heal from the trauma she personally experienced in the aftermath of a war that has claimed more than half a million lives.

In an ironic twist of fate, she eventually had to leave Damascus in 2013, after some of her friends had been detained by the government of Bashar al-Assad and several members of her family had fled the country. After securing a scholarship and earning a degree from King’s College London, where she explored the ways in which art can be used to preserve cultural memory, Nachawi moved to Beirut.

Nachawi hopes the exhibition will prompt people “to think outside of the box. The Syrian situation is complicated, but there is something to be clear about: civilians want to live in dignity,” she said.

Life Jackets

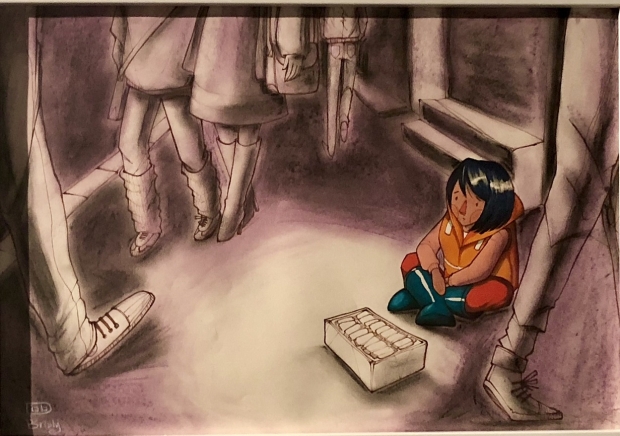

Diala Brisly, another Syrian artist, focuses on displacement and social justice in her work, which she refers to as “graphic journalism”.

When you’re away from your homeland, everything feels heavier. You experience sorrow from a distance

- Dima Nachawi, artist

Brisly’s sprawling works quickly garnered attention, not just internationally, but among the children of Lebanon’s refugee camps who started referring to her as “the artist”. Despite having to constantly grapple with her own struggles, she was galvanised.

“These children endure horrible circumstances at the camp, and I thought because many of them hadn’t been to school in a while, maybe art would encourage them to focus on learning,” Brisly said.

Haunted by memories of friends and colleagues she’d lost to death and detention in the aftermath of the uprisings in Syria, during which the artist secretly worked with various field hospitals by smuggling medical and food supplies, Brisly turned to art as a form of therapy. While she now lives in Paris, having sought asylum there in 2016, she still works with refugees, albeit from a distance via the non-profit Alphabet: Alternative Education.

Part of the profits from “Tints of Resilience” will go to Alphabet, which addresses the educational needs of children who have experienced an interruption in schooling due to the Syrian war.

‘Pouring my feelings’

In another piece, a mother and son walk among the ruins of their hometown in Syria, wearing life jackets. In a third, a young, lonesome refugee girl sits on the congested roads of Hamra in Beirut, selling bits and bobs for survival; she, too, is wearing a life jacket. “I wanted to say everyone needs life jackets, not just people in the sea,” Brisly said.

Everyone needs life jackets, not just people in the sea

- Diala Brisly, artist

Another four of Brisly’s canvases at the exhibit depict the artist going through different stages of her life as a displaced Syrian, under the titles Survival Mode, Solitude, Integration, and Shattered.

“I always ask children to draw themselves and to imagine themselves as something really important, because that can help them connect positively with themselves,” she said. “So now I’m doing the same, painting myself at different stages of my life. These paintings are extremely personal. I’m pouring my feelings into them.”

"Tints of Resilience" opened on 17 August and will run through 6 September at London's P21 Gallery.

Middle East Eye propose une couverture et une analyse indépendantes et incomparables du Moyen-Orient, de l’Afrique du Nord et d’autres régions du monde. Pour en savoir plus sur la reprise de ce contenu et les frais qui s’appliquent, veuillez remplir ce formulaire [en anglais]. Pour en savoir plus sur MEE, cliquez ici [en anglais].